Why Did Independence Parties Boycott New Caledonia’s Referendum?

Hardline French loyalists are risking a return to the rifts of the 1980s.

by Adrian Muckle

17 December 2021

In the French archipelago of New Caledonia (or Kanaky to the Indigenous inhabitants), a long-running struggle has sought to create the newest independent country in the Pacific. Following wars, resistance and concessions, France finally agreed in 1998 to carry out three referenda on independence.

Over two decades later, with the first two referenda ending in narrow victories for the French loyalist campaign, the final vote – held last Sunday – descended into farce. Boycotted by the independence movement, the resulting pro-French vote has been condemned by neighbouring Pacific states and rejected by pro-independence forces, such as the Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste, FLNKS). The resulting impasse threatens a return to the sort of political instability that led to violence in the 1980s.

The third referendum.

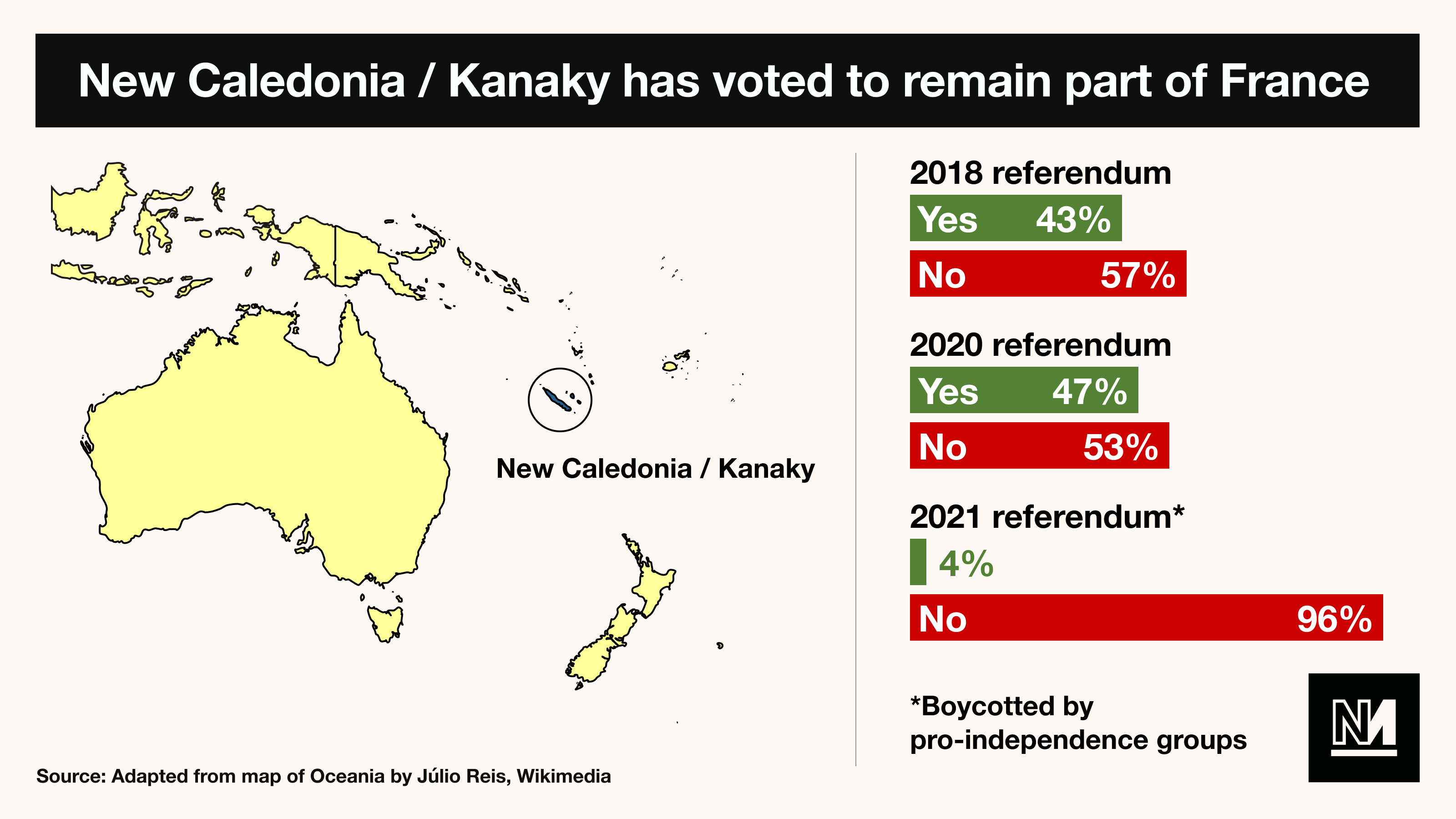

After New Caledonia’s pro-independence parties called on supporters to boycott this year’s independence referendum on December 12 — the final “consultation” allowed under the auspices of the 1998 Nouméa Accord — less than half of eligible voters turned out. The result was a crushing 96.5% against independence.

The turn-out and result contrast radically with the two previous referendums, in 2018 and 2020, in which the vote for independence grew from 43.3% to 46.7%, with participation over 80% each time. The vote for independence was expected to rise in the final showdown.

French President Emmanuel Macron immediately welcomed the result, proclaiming that New Caledonia will remain French and that France is “more beautiful” as a result. Hardline loyalist politician Sonia Backès crowed that the “sad dreams of independence at the price of ruin, exclusion and misery” had “broken on the reef of our pioneer soul, our resilience, our love for our own land”.

The result, however, has been categorically rejected by the mainly Indigenous Kanak pro-independence parties which steadfastly refuse to recognise the referendum’s legitimacy. Concern has also been expressed by leftwing presidential candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon as well as neighbouring countries in the Pacific. The secretariat of the sub-regional Melanesian Spearhead Group has offered support to help declare the vote null at the UN, and the regional Pacific Islands Forum has cautiously stated that account must be taken of the extent of “civic participation” and the “spirit” in which the referendum was conducted.

The boycott decision.

Independence parties boycotted the referendum that they themselves requested due to the outbreak of the Delta variant of Covid-19 on 6 September, shortly before campaigning officially opened. Previously almost untouched by Covid-19, New Caledonia’s population of 270,000 has now seen more than 270 deaths. Kanak and other Pacific islanders are disproportionately affected, and vaccination rates are relatively low.

In these conditions, it has been impossible to undertake the kind of grassroots campaigning required to reach remote rural communities and urban squatter settlements with often limited internet access. Drawing attention to the significant customary obligations that accompany mourning practices in Indigenous communities, the Kanak Customary Senate declared a period of mourning. All independence parties called for the referendum to be postponed until September 2022.

In remaining deaf to these appeals, the French government has revealed its determination to bulldoze the Nouméa Accord process, urged on by New Caledonia’s loyalist politicians. In choosing 12 December for the final referendum, overseas minister Sébastien Lecornu had already broken from a tradition of consensual dialogue. Édouard Philippe, former French prime minister, pledged in 2019 to “exclude” holding a referendum between September 2021 and August 2022 so as to minimise the risk of the debate on New Caledonia being inflamed by the forthcoming French presidential election.

While an electoral calculation was partly at play, the determination to proceed also resulted from the growing fear that pro-independence voters might have won a third referendum held under optimal conditions. The pro-independence vote increased by 3.4% between the last two referenda, and a shift in local political power earlier this year saw the formation of the first independentist-led government since the early 1980s.

Who should be able to vote in a settler colony?

Seen in its Pacific context, France’s decision to push through with the referendum not only undermines the 30-year-long peaceful decolonisation process – it also poses a setback for those elsewhere in the region who might have looked to New Caledonia for inspiration.

New Caledonia is not the only part of the Pacific where people are seeking formal independence. There are active struggles in West Papua (Indonesia), Bougainville (PNG), Guam (US) and French Polynesia (France), among others.

What has set New Caledonia apart, however, is the unique framework established by the 1988 Matignon-Oudinot Accords and Nouméa Accord. The first of these agreements ended a bitter period of bloodshed as conflict over independence intensified between 1981 and 1988. The second, guaranteed by an amendment to France’s constitution, allowed the gradual and irreversible transfer of many key powers from France to New Caledonia’s political institutions, begun redistributing resources between New Caledonia’s provinces (two of which are governed by pro-independence parties), recognised the Kanak identity, and set up not one but three binding votes on independence.

Crucially, for a former settler colony that until recently has experienced high rates of migration from France, the Nouméa Accord restricts the electoral rolls for the elections for New Caledonia’s three provincial governments and for the independence referenda to those persons with durable ties to New Caledonia. Today, this means the exclusion of more than 40,000 residents (mainly those arriving after 1988) from the provincial elections and some 35,000 residents (those arriving after a 1994 cut-off) from the referenda.

For Kanak people, who at 40% to 45% of the population have been a minority since the 1950s, this is a fundamental protection against France swamping their nation with settlers, swinging the vote through brute demographics (similarly a fear for West Papuans, rendered a minority by Indonesian settlers). The provision for long-term non-Indigenous residents to vote is also a welcoming hand to those with durable ties to New Caledonia, including the so-called victims of history – the descendants of French free and penal settlers and of indentured labourers from Asia and the Pacific, many of whom were sent to New Caledonia against their will and subjected to harsh conditions. In the eyes of loyalists, the provisions are exclusionary measures which run counter to French republican ideals of universality and the vision inherited from the 19th century of New Caledonia as la France australe (a France in the South Seas).

It is some of these progressive and decolonising institutional arrangements that loyalist politicians now have in their sights, having campaigned on the idea that a third ‘no’ vote will signal an end to the Nouméa Accord and the institutions it has created. This, however, is to challenge the depth of feeling that any attempts to change them will provoke. The breakdown of dialogue in the build-up to the referendum, the hardening of loyalist discourse, and France’s own abandonment of any pretence to neutrality does not augur well for the future. Independence leaders may seek another referendum, but will not discuss future political or institutional arrangements until after France’s 2022 presidential elections.

Parisian and settler worries block the path forward.

In its Pacific context, New Caledonia’s situation may seem surprising given that the main independence parties do not seek a hard break from France and have expressed the desire for a “partnership” or “association” agreement. Such arrangements exist elsewhere in the region, notably between New Zealand and its former territories of the Cook Islands and Niue, but also between the US and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. None of these countries, though, has a large non-Indigenous population that perceives the idea of association as a downgrading of relations with the metropole – as the politically powerful and wealthy elite of Nouméa do.

In advance of the referenda the pro-independence parties sought to discuss with France what such an arrangement might look like, but Paris and its local loyalists refused to engage, arguing that such discussions could only meaningfully take place after a successful independence vote.

A document prepared by French authorities for this month’s referendum on the implications of voting ‘yes’ or ‘no’ offered a stark contrast based on the (as yet) improbable assumption of a radical break following a pro-independence result. Evidently, French officials were concerned that any fleshed out ideas on independence-in-association might make a ‘yes’ vote more attractive to wavering loyalists, many of whom may be beginning to worry that their leaders are unable to find a way beyond an impasse of their own making.

Adrian Muckle is a senior lecturer in Pacific History at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.