Like It or Not, New Labour Offers Important Lessons for Saving the NHS

The Blair government reduced waiting times by nine weeks. That's hard to argue with.

by Ell Folan

3 January 2022

In the run up to Christmas 2021, the National Health Service was in a sorry state. The average waiting time for patients had reached 12 weeks; nearly 40,000 nursing roles were vacant; and hospitals were being told to discharge as many patients as possible to free up beds, even as bed numbers fell to a record low. The CEO of NHS Providers, the membership organisation for NHS Trusts, warned that the service was “heading for the most difficult winter in its history”.

It wasn’t always this way. As recently as 2009, wait times were as low as 4 weeks; there were fewer than 12,000 unfilled nursing roles; and there were 170,000 hospital beds, compared to 130,000 today. How did things change so quickly? And what can we do to fix it?

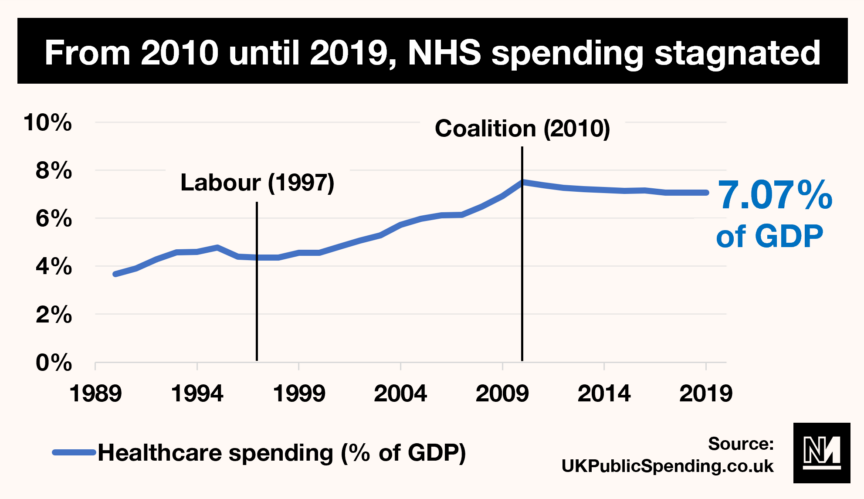

One of the major reasons for the decline in NHS services over the past decade is simple: money. Between 2010 (when the Conservative party took office) and 2019, government spending on healthcare declined as a share of GDP from 8% to 7%. By comparison, New Labour increased spending on healthcare by 56% in the preceding nine years, from 5% to 8% of GDP.

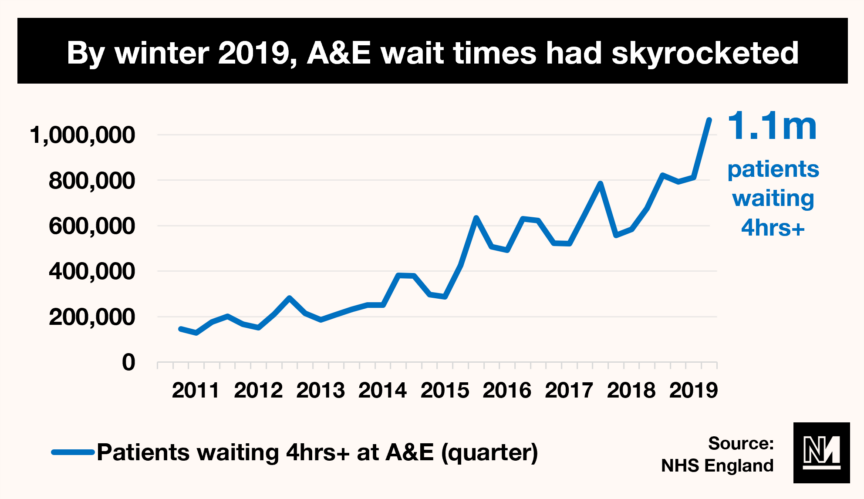

Since the pandemic began, healthcare spending has, unsurprisingly, risen substantially – it’s now 10% of GDP. But this was in response to unprecedented and overwhelming pressures, meaning the NHS is still treading water. Not only that, but a decade of low funding has had devastating impacts on the service that will not vanish overnight. In the third quarter of 2019, for instance, 1.1 million patients in England were left waiting for more than 4 hours in A&E due to pressure on services; in winter 2011, it was 176,000.

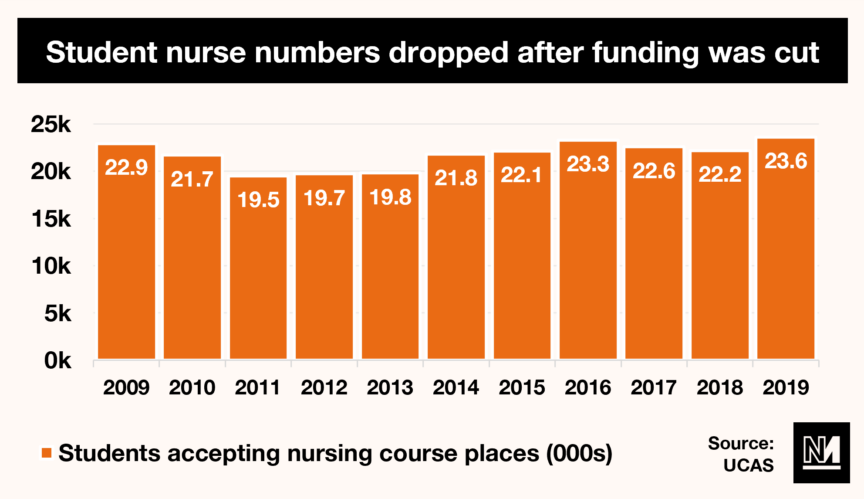

Cuts to service funding are easy to spot, but some cuts have been subtler. In 2011, the government reduced the number of nursing degree places they would fund, with ministers warning of a potential oversupply of nurses. Then in 2016, the government scrapped the NHS bursary for student nurses and midwives, which ministers argued would create more training places. Both of these changes led to clear and sudden declines in the number of student nurses. The Tories U-turned and restored the NHS bursary in 2019 – and lo and behold, nurse applications rose.

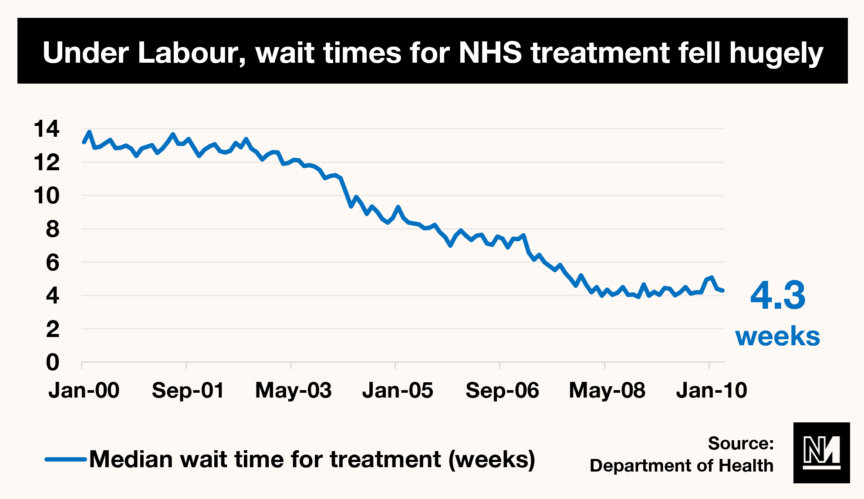

But funding changes are not the only policies that have affected the NHS since the Tories came to power. Between 1997 and 2010, New Labour introduced a variety of centrally managed targets for the health service, ranging from A&E waiting times to broader measures like life expectancy and inequality. Upon taking office, the Conservatives and Lib Dems scrapped many of these; just before the pandemic erupted, Johnson’s government was floating scrapping the A&E waiting time target entirely.

Whilst New Labour’s targets were not universally welcomed, they did bring about significant progress in treatment: between 2000 and 2010, the median wait time for hospital treatment fell from 13 weeks to four.

In addition to these cuts, the Conservatives introduced reforms that pushed the NHS into uncharted territory. The 2012 Health and Social Care Act brought more market mechanisms into the health service, made NHS England independent from government and created a byzantine series of new boards and bodies. Two years on, just 5% of healthcare professionals felt that the reforms had had a positive impact.

But if these are the problems, what can we do to fix them? The simple answer would be to rewind to2009, reverting to New Labour levels of funding, reintroducing targets and reversing coalition reforms.

But this should only be the first step in fixing the NHS. Things were not perfect under New Labour: the use of Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) to fund healthcare projects, for example, left the NHS and government owing tens of millions to private companies. The after-effects are still being felt today: 2019 data showed that some NHS trusts are now spending as much as one-sixth of their budget on PFI debt repayments. Moreover, it was Blair who introduced private market mechanisms into the NHS. Returning to the New Labour days is clearly not enough.

To bring the NHS back from the brink, a Labour government would need to return the service to its universalist principles. That means not only renationalising the NHS, bringing all of its various aspects back under direct public control, but also expanding its free-at-point-of-use principle to cover all elements of healthcare: prescriptions dental and eye care for a start.

Pumping more money into the NHS will suffice in the immediate term, but in the long term, it won’t. The next Labour government needs to be as bold as the one that created the health service, realising Nye Bevan’s dream of universal public healthcare, free to all at the point of use, controlled by and accountable to the public.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties.