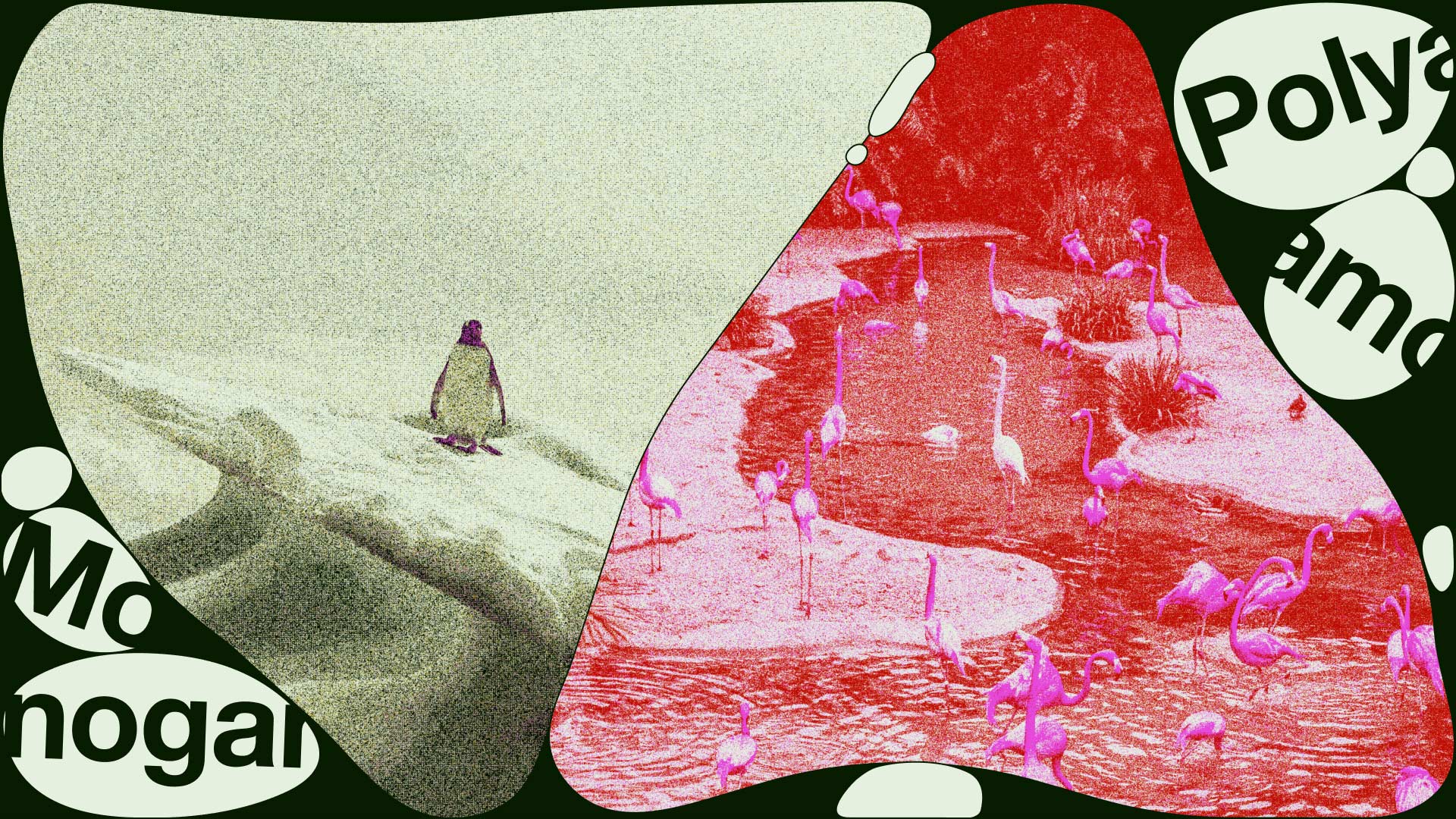

Monogamy Is Cool, Actually

As we’ve got used to browsing for new partners on our phones, we’ve also got used to stating our preferences in advance, whether we’re looking for LTRs, threesomes, Air signs or “no Tories”. If you’ve spent any time on “the apps” lately, you’ll know that increasing numbers of suitors are flagging their interest in polyamory, or more often “ENM”, which stands for ethical non-monogamy, the practice of having multiple consenting partners at the same time. If you’ve noticed that and you’re reading this, you may also harbour suspicions that a significant number of single lefties are into polyamory.

So what’s the connection between politics and pleasure? Is non-monogamy meant to be a political act? Practitioners often argue that relationships outside of monogamy are inherently subversive, not only for committing the mortal sin of adultery, but because the heterosexual couple is the first stage in the process of creating the patriarchal nuclear family, a basic cog in our oppressive system. Rejecting monogamy, they claim, must be an affront to that system. If it’s true that reorganising our private relations can disrupt the injustice of the social and economic order, then all of us progressives should be considering ethical non-monogamy as a form of praxis, right? But the poly proselytisers have got it backwards.

Fordist families.

The surge of interest in non-monogamous relationships first has to be couched in the understanding that monogamy has only ever been a demand made on women. In modern times adultery and prostitution are spoken of as shameful secrets, but for the Greeks and Romans it was out in the open. Husbands were expected to engage in “hetaerism”, the ancient mode of playing away with prostitutes, concubines and slave women, but their wives were not afforded the same sexual freedoms. Speculating on the evolution of marriage customs, Friedrich Engels thought that monogamy emerged alongside slavery and private wealth in order to “procreate children whose fatherhood is indisputable […] because children, as direct heirs, will one day enter into the possession of their father’s goods.” In making the connection between monogamy and property, he proposed that monogamous marriage emerged alongside the beginning of class oppression, an era in which prosperity for the few would be won through the misery and frustration of the many.

As economic models changed, so did our idea of the ideal relationship. By the early twentieth century, the monogamous family was the bedrock of the Fordist economy, with the archetypal husband going to work in a factory and coming home to his wife, whose cooking and cleaning was the unpaid, unrecognised work that enabled him to clock in on time every day. This cosy setup held no appeal for Engels, who described such “Protestant monogamy” as “a conjugal partnership of leaden boredom, known as ‘domestic bliss’”.

When the era of picket-fence Fordism was swept away by flexible production, the rise of global finance and the destruction of the unions, the monogamous nuclear family came under pressure. As women acquired new reproductive, workplace and financial rights – such as the ability to take out a mortgage, which even in the 1970s often required the signature of a male guarantor – the customs of marriage and monogamy became less relevant to capital and more likely to be perceived as a personal and moral matter.

Free agents.

Engels also predicted that in a communist society, when we are rid of “all this anxiety about bequeathing and inheriting”, people will be free to enter into any kind of relationship they want: “They will care precious little what anybody today thinks they ought to do.” Freedom is certainly one of the motivating principles of polyamory. “I’m my own person and no one owns me. I don’t own any of you, either. We’re all free,” explained one polyamorist in a Guardian profile in 2018. Their vision of individual freedom is well-suited to a capitalist understanding of human beings as both autonomous, rational actors and self-involved, pleasure-seeking consumers.

Think of polyamorous partners negotiating the terms of an open relationship: two or more free and equal agents making a rational decision based on their own desires, openly shared with each other. Is this radical? Or are these polyamorous lovers something more like niche-market consumers, with specific proclivities and an almost solipsistic sense of independence? In response to the Guardian article, one reader wrote in to point out that all modern relationships, whether monogamous or polyamorous, are spoiled by “the values currently celebrated in capitalist culture: narcissism and hedonism.”

Alternatives to individualism.

For polyamory to offer a progressive alternative to traditional monogamy, it needs to propose an alternative to the individualism which is both a bedrock of capitalism and its tragic effect. Instead, it can end up doing the opposite – especially when polyamory is reduced to a badge on a dating profile, or worse, used as a fig leaf for philandering tourists with no interest in deconstructing relationship norms.

The benefits of being in a polycule are often framed in utilitarian terms, where the ideal romantic arrangement produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Instead of seeking out one ideal partner, you relax your expectations and take the best bits from multiple partners. If your polycule provides you with hot sex with one person, intellectual sparring with another and tell-all intimacy with a third, then congratulations – you’ve grabbed a deal. In this bargain hunt, any product found to be defective can be easily exchanged for a better one.

This is a risk mitigation strategy, not a radical new vision of love. Far from being anti-capitalist, it’s rooted in the same relentless pursuit of pleasure that reduces us to consumers in every facet of life. In comparison, monogamy – with its emphasis on the boring work of compromise and coalition – starts to look like the more radical option. It might not have the sexy, slippery flexibility of the polycule, but the stolid monogamous unit has its own austere appeal. It signifies a commitment not just to the things you like about someone, but the things you don’t like – all their annoying habits and the unfortunate traits, their needs and liabilities.

Declaring your devotion to just one imperfect person is a refusal of a disposable attitude to relationships. That doesn’t mean subordinating yourself to someone else’s demands or getting bogged down in abusive power dynamics. But monogamy does suggest a dedication to something bigger than yourself, something known to be extremely difficult. When a third of marriages end in divorce, it takes a weird kind of zealotry to stroll up the aisle and promise to stay together, in sickness and in health. They declare themselves “off the market”. In refusing other options, they acknowledge that love and care are impossible to calculate or price up, and are often complicated by feelings of boredom, irritation, anger and jealousy. The challenge is to stick rather than twist.

Just as monogamous marriage came about as a reaction to emerging notions of property ownership, so the prospect of ethical non-monogamy arises in time for a new cohort of sexually liberated, economically independent consumers to take advantage of it. Which leaves us with the question: what kind of sexual relations would emerge if capitalism was overthrown? Engels, whose own love life was certainly unconventional, admits he has no idea. “That will be answered when a new generation has grown up,” he writes. “They will make their own practice and their corresponding public opinion about the practice of each individual – and that will be the end of it.”

Chal Ravens is Novara Media’s head of audio.