When Will the West Stop Underestimating the Far Right?

In 2016, Vox won 0.2% in Spain. It's now polling at 23%.

by Ell Folan

1 March 2022

It might seem difficult to believe as an army led by a far-right dictator invades a European nation, but in recent years, the European far-right has been considered relatively marginal. In April 2019, for instance, the far-right Vox party won seats in the Spanish parliament for the first time – but even this was dismissed by Slate as “not the triumph Vox had hoped for”. Although Vox – an ultra-conservative party that opposes gay marriage and favours restrictions on migration – went on to gain more seats in the December election, they struggled to grow; one expert on the far right wrote in 2020 that none of the party’s strategies had “proved particularly effective in enhancing Vox’s political fortunes”.

In the past few months, that has changed. In recent polls Vox has risen as high as 23%, ahead of the centre-right People’s party, and are now propping up conservative regional governments in Madrid, Andalusia and Murcia.

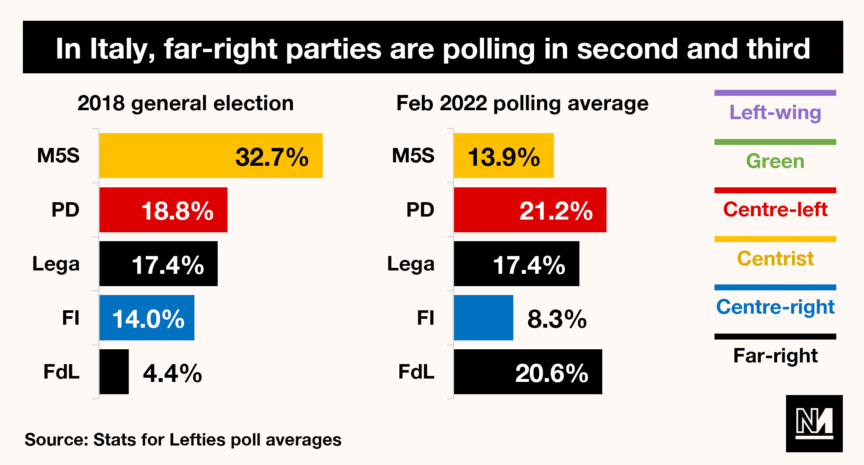

But Vox isn’t the only far-right party whose support is growing in Europe. In Portugal, Chega – whose leader invited France’s Marine Le Pen to join him on the campaign trail – grew from 68,000 votes in 2019 to 410,000 in February’s snap election. In Austria, the Freedom party has rebounded from an embarrassing 2019 defeat and is now polling close to a quarter of the vote; in Italy, meanwhile, both the Northern League and the Brothers of Italy are polling at or close to 20% each.

In Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, meanwhile, the far-right government looks likely to once again emerge victorious in April, even after all of the main opposition parties united behind a single slate.

Yet despite all this, across Europe and America, liberals and the media have a terrible habit of triumphantly pronouncing the defeat of the far right only to watch in horror as it returns stronger than ever before.

In the past two years, The Economist has dismissed the European far right as “inept”; The Week has said it was “running into its limits”; the Financial Times has stated it is “stumbling”; while Politico’s Europe branch has argued that far-right parties were “struggling to find a coherent message” on Covid-19.

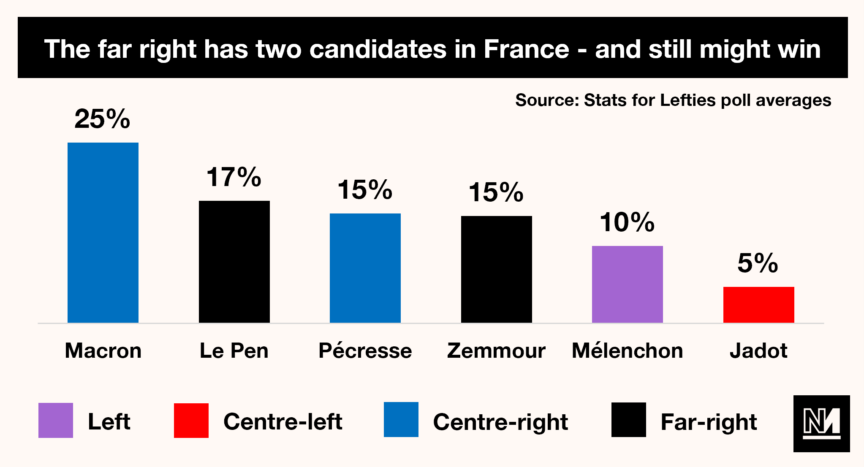

Yet they may be proven decisively incorrect. In France, the defeat of far-right candidate Le Pen by centre-right Emmanuel Macron in the 2017 presidential election was celebrated as a repudiation of the far right. Now, it looks like Le Pen and her far-right comrade Éric Zemmour may between them capture 32% of the vote in the first round, with Le Pen looking likely to win more than 40% of votes in the final round even if she ultimately loses to Macron.

The UK has its own bitter history of underestimating the far right, of course. In the 2010 general election, the failure of Nick Griffin’s British National party – which at its peak in 2009-10 held two members of the European parliament and a few dozen local council seats – to win Barking from Labour was held up as a devastating defeat for the British far right. Yet within four years, Nigel Farage’s UK Independence Party (Ukip) had two seats in the Commons. When in turn Ukip collapsed, Farage bounced back with the Brexit party, which swept the 2019 EU elections with 29 seats.

Yet perhaps the most concerning example of underestimating the far right occurred in the United States. In the aftermath of Donald Trump’s electoral defeat in November 2020, many liberals rejoiced at what they regarded as the banishing of a far-right ghoul. Politico declared that he would “fade away” whilst Joe Biden predicted that Republicans would have an “epiphany”. Yet more than a year after the presidential election, Trump’s grip over the Republican party is stronger than ever, with the man himself enjoying approval ratings of upwards of 80% among Republican voters. Equally robust is the movement he inspired: Trump’s rallies continue to attract huge crowds, while pro-Trump candidates challenge incumbents across the US.

The mistake we are making is to conflate the defeat of one party or politician with the defeat of their ideology or movement. The problem, of course, is that as long as the beliefs that drove those people or parties to prominence remain (racism, homophobia, sexism), there will always be someone willing to express them.

This is exactly what has happened throughout Europe and in America. In France, for instance, Macron has done little to repudiate the bigotry that powered Le Pen’s campaign – in fact, he even backed the continuation of France’s hijab ban and called for new caps on immigration. In Britain, the ideas that drove the BNP to prominence have gone virtually unchallenged by the nation’s leaders, with Boris Johnson – who has previously praised Donald Trump – abandoning Theresa May’s proposals to strengthen transgender rights and passing a borders bill that aims to discourage people from seeking asylum through irregular means. Joe Biden, meanwhile, has sought to keep many of Donald Trump’s immigration policies.

Across the west, the far right is on the rise. Defeating individual parties or politicians will not change this. Nor will piggybacking off of far-right rhetoric in the hopes of siphoning off votes. Instead, politicians need to challenge the bigotry that the far right leverages and incites, and enact socially liberal policies that make society more tolerant. The alternative, as we are seeing on the streets of Kyiv, is unthinkable.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties.