A Prestigious London University Has Suspended Four Latinx Cleaners for Protesting Racist Pay, Falsely Accusing Them of Violence

The good news is they may be suing.

by Polly Smythe

4 May 2022

On 22 April, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), a prestigious public health research institution that counts England’s chief medical officer Chris Witty as an alumnus, suspended four outsourced cleaners after they protested a racist pay gap, falsely claiming that the protesters were violent. The race scandal is the latest to hit the university in five months.

In a statement to Novara Media, LSHTM said it while it “wholeheartedly supports the right to peaceful demonstration”, the suspensions were justified as “our security staff were threatened and pushed aside as around 18 demonstrators … forced entry into the building”. Video footage from the protest (embedded below) shows no force being used to enter the building. LSHTM’s full statement is below.

A two-tier employment system.

Since August, workers at LSHTM, supported by the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain (IWGB), have been campaigning for the university to end its two-tier employment system, one that sees in-house staff treated far better than outsourced workers. After some early wins – annual leave, improved sick pay and paternity leave – LSHTM announced its intention to in-house cleaners, porters, post-room staff and security guards. There was, however, a catch: LSHTM planned to pay the newly in-housed workers £11.05 an hour, less than the lowest grade of the University’s pay structure – and substantially less than the £14.38 an hour university maintenance staff receive.

🚨BREAKING NEWS🚨

The IWGB union has given a deadline to @LSHTM : Bring your cleaners, security and porters IN-HOUSE NOW!

DEADLINE DAY is set for August 30👀

End OUTSOURCING or face a powerful campaign from LSHTM’S outsourced workers and the @IWGBunion 🔥

Whatch this space! pic.twitter.com/v0Hl7iFHET

— IWGB Universities of London (@IWGBUoL) August 4, 2021

After a series of in-housing meetings, the university refused further negotiation, though they confirmed that workers would not receive a pay cut upon being in-housed. Frustrated with this decision, the IWGB announced their intention to peacefully protest outside LSHTM on 21 April. Workers felt this was their only option: “All we were doing is asking for the university to listen,” Jenny Sanchez, 43, who is Colombian and has worked as a cleaner at the university for five years, told Novara Media via a translator. “This is the only way we have to make ourselves heard.”

“They treat us like nobodies.”

For Henry Chango Lopez – the general secretary of the IWGB and former cleaner for the University of London, where he was instrumental in a 10-year in-housing battle – the school’s refusal to improve pay for outsourced workers is a continuation of “the racist two-tier system LSHTM [has] presided over for years”.

The roughly 40 outsourced workers at LSHTM – most of whom are people of colour, many of them Latinx – are denied many of the benefits their employed colleagues enjoy. For example, LSHTM subsidises employees’ petrol and congestion charge, but when outsourced workers asked to be included in this scheme, they were told to walk or cycle. Outsourced workers claim they are the only ones exempted from the school’s six annual “director’s days”, holiday days granted to staff in addition to annual leave and public holidays. (LSHTM claims that all staff – including outsourced workers – receive full pay during the closure, although outsourced workers still have to work.)

“Because we’re cleaners, they treat us like nobodies,” Sanchez told Novara Media.

While the school played an instrumental role in guiding the government’s response to Covid-19, outsourced workers felt their ill treatment most acutely during the pandemic. At its start, Rene Lozano, a 56-year-old Columbian man who has worked as a porter at LSHTM for 14 years, was sent to clean a laboratory after a lab worker had become infected with Covid – without being informed of the protocols for disinfecting.

“From a university that has hygiene in its name, this is not okay,” he told Novara Media. He reckons that the vast majority of his colleagues became infected with Covid-19 while working for LSHTM. Multiple other workers who spoke to Novara Media said colleagues had been disciplined for sharing their Covid status with other workers.

Structural racism.

This is not the first time LSHTM has been accused of racism.

Founded by the UK government’s Colonial Office in 1899, the school was intended to provide training for colonial medical officers and to research tropical medicine to enable Britain to continue expanding its empire. Far from tarnishing its reputation, the university’s colonial origins have, according to staff and students, cemented its position as a leader in global health research. It has been far more detrimental to those inside the institution, however.

The suspension of four migrant workers comes just a few months after the publication of a damning review investigating structural racism at the LSHTM. The independent report, published in December, found that “the colonial attitudes inherent in LSHTM’s historical mission negatively impact students and staff of colour today”.

Narcisa Salgado, a 59-year-old Ecuadorian woman who has worked as a cleaner at the university for five years, notes that the review focused singularly on staff and students. “The report was just for themselves,” she says. “We’re invisible to them, they don’t count us as people. Most of the outsourced staff are migrants, but the report only looked at who is convenient for them.”

“We aren’t criminals.”

In the days leading up to the 21 April protest, LSHTM geared up staff for an onslaught. On the day of the protest, staff received an email from management informing them that they would need to present ID cards to gain access to university buildings and that additional security officers would be in place “to ensure your safety and minimise any potential disruption”.

This is how @LSHTM reacts to organised BAME workers demanding equality – treating us like criminals.

When UCU goes on strike the managers offer meetings. When we protest they refuse to negotiate and clamp down on us. Shame on LSHTM. pic.twitter.com/xbfbwFMgHT

— IWGB Universities of London (@IWGBUoL) April 21, 2022

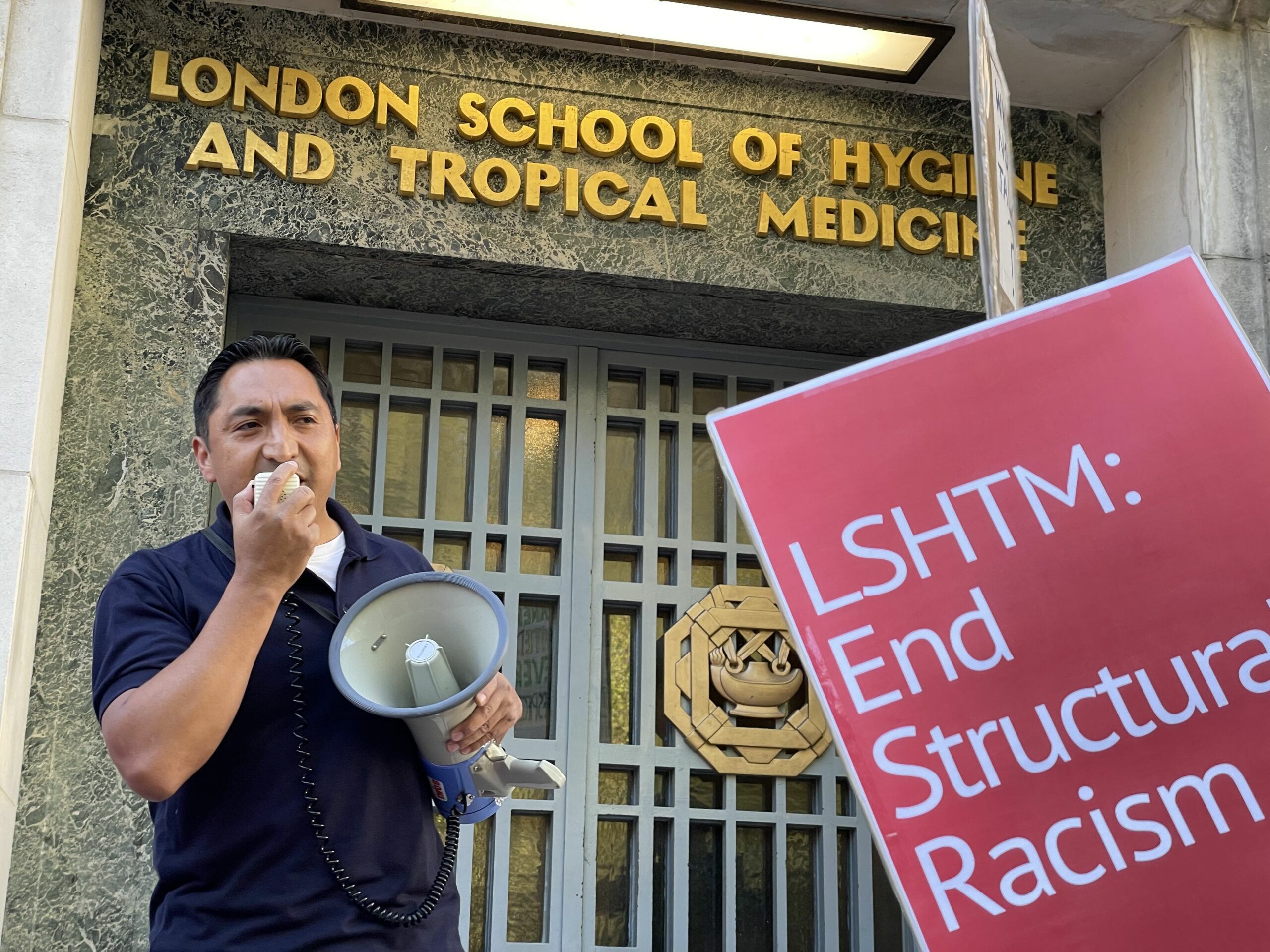

The disruption in question consisted of music, drumming and chanting; around 30 workers and their supporters waved banners with slogans like “Cleaners United Never Disrespected” and passed around a megaphone sharing stories of their mistreatment.

Today @IWGBUoL cleaners, porters & security at @LSHTM protested for fair pay.

LSHTM have promised staff they will be brought in house, but refused to pay them the same as their in housed colleagues.

We will not stop fighting until workers at LSHTM get the pay they deserve! pic.twitter.com/ksBaECC1fH

— IWGB (@IWGBunion) April 21, 2022

Sanchez had been nervous about taking action. Afterwards, she was glad she did, hoping that her boldness would inspire the same in others: “Some people are scared to join [the union],” she told Novara Media. “But we’re in the union, and we’re putting our necks on the line for others.”

Eventually, the protestors made their way inside the building in the hopes of speaking with LSHTM management who had refused to return to the negotiating table. They didn’t get far: soon after the protestors entered the building foyer, LSHTM’s head of security called the police; three police cars arrived not long after. Salgado was confused: “But we aren’t criminals, we’re just exercising our right to peacefully protest.”

A phone call in English.

On 22 April, the day after the protest, four workers who had attended the protest – Salgado, Lozano, Sanchez, and a fourth worker, Adrian Carlos – were suspended on the grounds due to their having participated in the protest. All were initially informed via a phone call in English, which Sanchez does not speak.

The suspension, which is indefinite, has thrown the workers into turmoil. “We’re in limbo […] the wait feels eternal.” Salgado says the stress has made her physically ill.

Still, she hopes the university will lift the suspensions – although she fears there may be strings attached. “They might put conditions on our return to work, telling us we can’t protest,” she told Novara Media.

Demonising protesters.

While the four protesters were informed that their suspensions were due to their participation in the protest, the university’s statement two days later offered a different reason.

Last week a demonstration organised by the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain took place at Keppel Street.

LSHTM is committed to making the School a great place to work and study for everyone, and the safety of our staff and students is paramount.

Our statement ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/pVjN2MEInM

— London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (@LSHTM) April 24, 2022

In the statement dated 24 April, LSHTM claimed that the suspensions were the result of workers entering the workplace without authorisation, as well as having “threatened” and “pushed” security staff to enter the building “by force”. IWGB categorically denies this claim, pointing to video footage showing protesters peacefully entering the building.

Despite this, university management has repeated its false allegation to students and staff, writing in an email that protestors “physically forced their way past security staff” to gain “unauthorised access” to the building, although “fortunately no one was injured”.

Lopez is unsurprised by the university’s divide-and-rule tactics: “They’re creating […] division between workers who all work in the same building. We’ve seen these tactics before.”

Foul play.

The IWGB believe the four workers have been penalised for their trade union activity – illegally so.

On the day of the suspensions, the union wrote to both the university and Samsic stating its intention, if the suspensions are not reversed, to take legal action against both parties, arguing they have breached section 146 of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992, which protects workers against unfair treatment from an employer over trade union activities, as well as article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which grants the right to form and join a trade union.

🚩 Solidarity guard 🚩 with the suspended LSHTM cleaners this morning outside the investigation hearings at Samsic offices.

We call on @LSHTM and @RegentSamLondon to reverse these unjust suspensions now! ✊🏿✊🏽✊🏻 pic.twitter.com/dgqJgVkYrG

— IWGB Universities of London (@IWGBUoL) May 4, 2022

In a public statement, Lopez described the suspensions as “a blatant act of aggression and an attempt to intimidate cleaners into backing down”. The workers appear unfazed: “Being a cleaner does not make one less-than,” Salgado told Novara Media. “LSHTM must drop their superior airs and treat us equally.”

A spokesperson for LSHTM said:

“LSHTM wholeheartedly supports the right to peaceful demonstration. Unfortunately, on this occasion our security staff were threatened and pushed aside as around 18 demonstrators (including 4 staff employed at LSHTM via Samsic UK) forced entry into the building.

“As a research-intensive university, LSHTM is home to high-risk areas including secure research facilities and microbiological laboratories in which certain restricted pathogens or toxins are handled. We therefore have rigorous security restrictions for entering our buildings, in line with strict requirements from the UK Government and our health and safety obligations. A breach of our security measures requires the police to be called.

“Four Samsic UK employees have been placed on suspension as a holding measure to enable the company to investigate allegations that they enabled access to the premises of the LSHTM during a protest organised by the IWGB union, when requested not to. Samsic recognises and supports the right to protest but cannot condone forcible entry. The company will comment further on the matter when its investigation has been concluded.”

Polly Smythe is Novara Media’s labour movement correspondent.