Spain’s Democracy is Being Undermined by Deep State Actors

‘Catalangate’ has rocked Spanish politics.

by Eoghan Gilmartin

5 May 2022

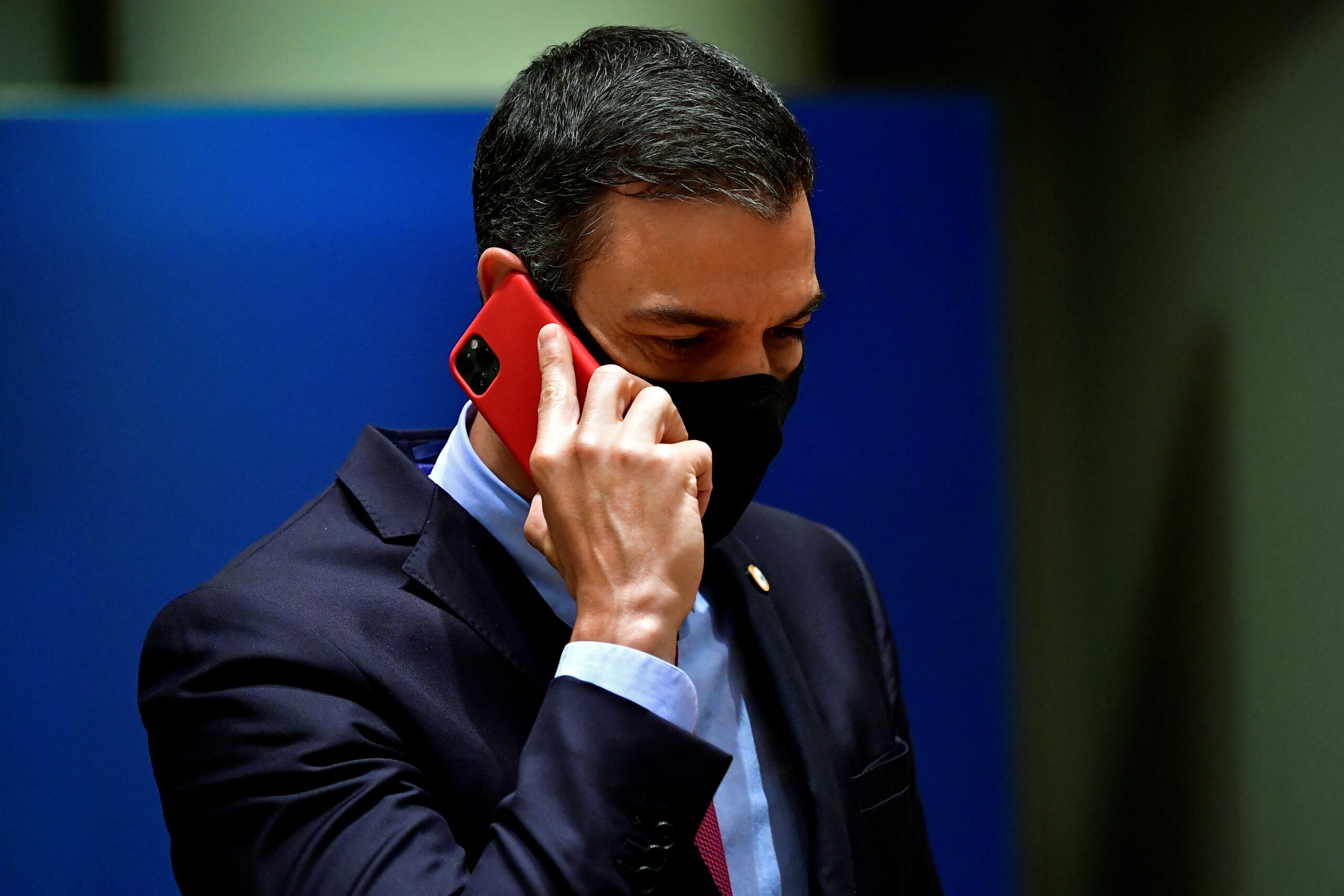

On Monday Spain announced that Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s phone had been hacked using Pegasus spyware, in what is the first government-confirmed case of an attack against a national leader anywhere in the world. Yet this was just the latest incident in a much wider political espionage scandal that has rocked Spanish politics and once again laid bare the democratic deficiencies of the country’s post-Franco constitutional regime.

The case broke in mid-April when it was revealed that 65 prominent figures within the Catalan and Basque independence movements had been targeted by Pegasus. A product of the Israeli cyber-arms company NSO Group, the spyware is sold exclusively to government agencies in order to carry out surveillance by infecting phones with malicious software. According to a report from University of Toronto’s CitizenLab, between 2015 and 2020 not only were the phones of leading Catalan politicians hacked (including those of the last four regional presidents), but also devices belonging to Catalan activists, lawyers and journalists.

“I have no doubt it was the Spanish authorities who hacked my phone,” Jordi Solé, a Left Republican member of the European Parliament, tells Novara Media. “This is ideological persecution. There is no legal basis for this under Spanish law and it seems unlikely that the intelligence services obtained the necessary court authorization to target me.”

Such outrage is also echoed by centre-right Catalan MP Ferran Bel, another of the confirmed victims: “This is a wholesale invasion of my personal and family life, as well as an attack on my status as a democratic representative. We are not talking about simply bugging a phone line. Once Pegasus infects your mobile, it copies all of your emails, WhatsApp messages and photos as well as having the capacity to turn on your microphone and camera. But beyond my own right to privacy, ‘Catalangate’ raises serious questions more generally about the rule of law in Spain.”

The spyware attacks span three governments, beginning during the rightwing administration of Mariano Rajoy but with the majority of the infections taking place under the two terms of Socialist Party (PSOE) prime minister Pedro Sánchez. He and other PSOE ministers initially sought to downplay the scandal, denying that the intelligence services had engaged in any illegal activity and casting doubt on the CitizenLab report.

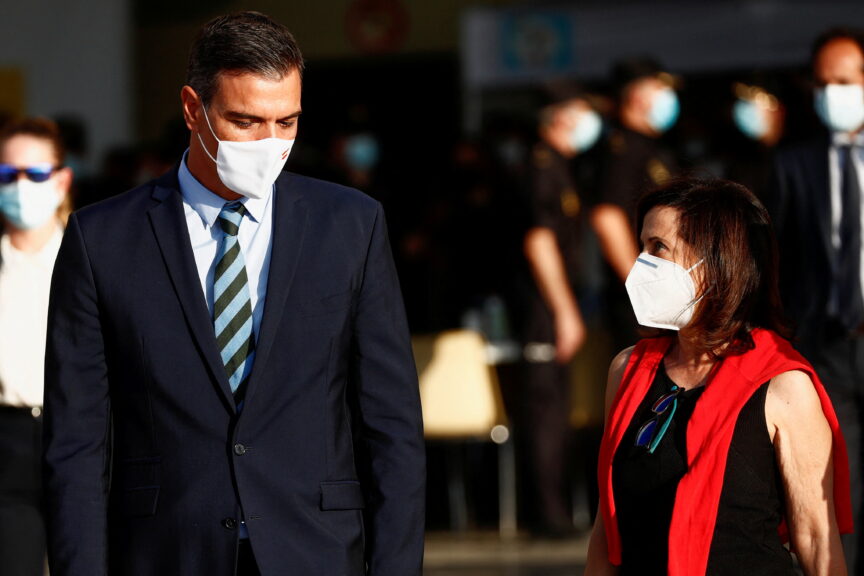

Yet revelations on Monday that Sánchez’ own phone and that of his defence minister Margarita Robles were also targeted by Pegasus further deepened the crisis. They also raised fresh questions about who was ultimately responsible for such espionage. “Is this a [government] smokescreen designed to give persecutors the appearance of being victims and to divert attention abroad?”, tweeted the anticapitalist Catalan MP Albert Botran. “Or is the CNI [National Centre for Intelligence] itself spying [on Sánchez’s administration] in the name of defending ‘the unity of Spain’?”

No conclusive answers are possible yet. Leaks to the press suggest, at the very least, that Sánchez’s first short-lived caretaker administration authorised (with judicial clearance) a smaller number of spyware attacks in 2019 against Catalan activists organising a campaign of mass civil disobedience. Yet the scale of Catalangate increasingly looks to stretch far beyond any government (or court) sanctioned operations. Instead, such mass surveillance seems further proof that beyond the electoral rise of the neo-Francoist Vox party, Spain’s basic democratic standards are being undermined from within by a series of reactionary actors within the upper echelons of the state.

The state sewers.

Spain has a strong record on social liberal reforms, being among the first states to pass equal marriage and gender violence legislation, while equality minister Irene Montero is currently finalising a landmark trans rights law. It is also the only major European nation in which the radical left sits at cabinet, with Unidas Podemos holding five ministries within the PSOE-led coalition. Yet for all this, Spain now finds itself on a list with illiberal Poland and Hungary as the only confirmed EU states who have used Pegasus to spy on its own citizens for political ends.

For Unidas Podemos MP Txema Guijarro, “Catalangate is a further effect of Spain’s badly executed transition to democracy [in the 1970’s], with elements within the intelligence services still capable of acting beyond democratic control.”

Basque senator Gorka Elejabarrieta, whose leftwing EH Bildu party was another victim of the Pegasus attacks, also points to the failings of the Spanish transition, telling Novara Media: “Rather than a rupture or clean break with Francoism, there was only a reform of the existing state regime, with no purging of the Francoist judiciary, police or security services. No one was made to pay for what happened during the dictatorship and this culture of impunity was carried over into the post-Franco era, most brutally in the Basque country. You have a state anchored in a series of opaque and unaccountable institutions, beginning at the top with the monarchy.”

Over the last decade these state elites have come to take an increasingly active role in politics, particularly in response to two anti-establishment movements that surged in the polls in the 2010s: the Catalan independence movement and the radical-left Podemos. The clearest example of this is the judicial crackdown on Catalan sovereignists since 2017’s outlawed independence referendum. 12 Catalan leaders were handed punitive jail sentences in a highly politicised trial after they were convicted of sedition for their part in organising the vote (though they were later pardoned by Sánchez’s left-leaning coalition). Dozens more officials are currently facing prosecution over the referendum, while others, such as former president Carles Puigdemont, sought exile in Belgium and Switzerland.

“We now know that during the sedition trial, four of the Catalan leaders’ lawyers were also targeted by Pegasus”, Left Republican [ERC] MP Carolina Telechea Lozano tells Novara Media. “This represents a dangerous precedent for political dissidence more broadly in the Spanish state. We have to ask: did the prosecution receive information about the defence strategy? Were these leaders’ right to a defence violated? At the very least, there are major concerns around client/attorney confidentiality being breached.”

Yet probably the key precedent for understanding Catalangate was the creation of the so-called Patriotic Brigade, a group of high-level police officers and Interior Ministry employees who were tasked with damaging the political rivals of Mariano Rajoy’s People’s Party (PP) government (2011-2018). As the name suggests, with its nod to the Francoist secret police, this was a group of reactionary state officials who saw themselves engaged in an ideological war with Spain’s enemies, i.e. Podemos and Catalan and Basque parties.

Overseen by the disgraced police chief José Manuel Villarejo, the group was involved in the theft of the phone of Pablo Iglesias’ assistant and the fabrication of police files smearing independentist parties and the radical left, as well as engaging in illegal wire-tapping and corporate spying for various Spanish oligarchs. A 2017 Spanish parliamentary inquiry found that the brigades’ “investigation and persecution of political adversaries” took place with “the knowledge and consent” of the PP’s Interior Minister Jorge Fernández Díaz, who is currently awaiting trial.

Yet this issue is systemic, with various ministers in the current PSOE-Unidas Podemos coalition also having been subject to bogus criminal investigations which have seen public prosecutors, judges and police repeatedly collude to undermine the authority of the executive. In one instance, Sánchez’s administration was forced to fire the commanding officer of the Civil Guard in Madrid for faking incriminating data in a report aimed to take down the country’s Interior Minister.

Political espionage.

“We don’t have all the facts but my thesis on Catalangate is that there is a similar type of ‘patriotic brigade’ operating within the CNI intelligence services to that of the national police”, explains Guijarro. “Guided by the sacred principle of defending the unity of Spain, which for them trumps any question of democracy and due process, these soldiers of the state are acting on their own autonomy. But in the past when we have had these deep state operations, there was always a political godfather behind it, who opened certain doors and facilitated such operations.”

A recent report in La Vanguardia newspaper backs up his thesis, pointing to the CNI’s creation of a Unit for the Defence of Constitutional Principles during the Rajoy years. This special unit was initially set up “to protect the monarchy” from further corruption scandals after the abdication of Juan Carlos I in 2014, but “soon turned to concentrate its investigations on the [Catalan] independence movement”.

Lozano also points to the dark underbelly of the Spanish state: “These unaccountable apparatuses ultimately count for more than the party in government. But I also find it hard to believe that no one in the current administration was conscious of what was happening.” Her ERC colleague Solé agrees, noting that “even if those who are politically responsible for our surveillance were themselves also being spied on, this does not absolve them of such responsibility or diminish the seriousness of the situation”.

Guijarro, who is head of the Spanish parliament’s budgetary committee, would not be drawn on who he thought this “political godfather” is, but he rules out Sánchez as being behind the Pegasus attacks. Bildu MP Jon Inarritu, who is one of the 65 victims, does too: “My sense is no, it was not him who ordered it”, he told Spanish media. Yet Sanchez has repeatedly chosen a non-confrontational stance with these deep state actors, installing very conservative figures as interior and defence ministers in an apparent peace gesture. Now many Catalan politicians see these two ministers as heavily implicated in the scandal.

Emboldening the extreme right.

“We independentists gave our parliamentary backing for the formation of the current progressive coalition”, Elejabarrieta notes. “This was partially due to an agreement around democratic reforms of the state, which still have yet to materialise. We now need a serious and independent investigation of these spying cases and a wholescale cleaning-out of those involved in such illegal activity. We are also convinced this spying is still ongoing right now, and that it has involved many more cases than those which have been confirmed.”

Yet PSOE’s stance since the scandal erupted has been to avoid confronting these abuses of state power directly, even breaking with its coalition partners and other allies to vote down a parliamentary commission into Catalangate. “The Socialists’ cynicism and unwillingness to engage with us is incredible”, Solé laments. “They are refusing to acknowledge the gravity of the violations. In the European Parliament we also had to overcome their opposition to secure a debate on the affair”

Even the public confirmation of the spyware attack on Sanchez’s phone seems largely a diversionary tactic to deflect heat away from the government. Indeed, it is far from clear that these government breaches are directly related to the mass surveillance of the Catalan independentists but instead could be the work of Moroccan intelligence, given that the two countries were locked in a diplomatic standoff at the time of the hack.

This is disputed, however, by Sánchez’s former deputy prime minister and Podemos’ historic leader Pablo Iglesias. The latter has insisted that it is more likely it was the government’s own intelligence services who targeted ministers, not least because the spyware attacks also coincided with sensitive negotiations over the pardoning of the jailed Catalan leaders. Many of those in the defence and judicial hierarchy were up in arms over this decision and sought to shatter such dialogue between Madrid and Catalonia.

In either case, these powerful actors within the state ultimately view Sánchez’s government, with its “communist ministers” and depending on the support of Catalan and Basque parties, as illegitimate. But against their constant aggression, Sánchez seems incapable of anything more than appeasement – even if this means he risks losing the votes of the pro-independence forces on whom his parliamentary majority rests. His government will likely struggle on, but with Vox now waiting in the wings, this failure of conviction could have tragic consequences.

Eoghan Gilmartin is a writer and translator covering Spanish politics.