Get Ready for Decisive Action From Liz Truss – but Don’t Expect It to Last

At least Thatcher promised real change.

by Aaron Bastani

5 September 2022

Now that Liz Truss has finally been confirmed as Conservative party leader and Boris Johnson’s successor as prime minister, you’ll read a flurry of pieces about her merits – and more often her deficiencies – for the top job.

The former will intone how Truss can mobilise the Tory base with a clear message on tax and growth. They will insist she is unafraid to embrace fracking and will happily tackle the disease of wokeness, where Boris Johnson apparently could not, primarily because of his wife.

The other side’s arguments are equally predictable. They will focus on the claim that Truss is intellectually underwhelming – that she lacks the requisite talent to pull her party out of the mire. Where supporters see a woman of conviction, critics point out that Truss was not only a Liberal Democrat in her formative years (she was even president of the party society at university) but backed remain as recently as six years ago.

But ultimately, it doesn’t matter what Truss’s supporters think. It doesn’t matter what her critics think. It doesn’t even matter what the likes of Rupert Murdoch or Lord Rothermere think.

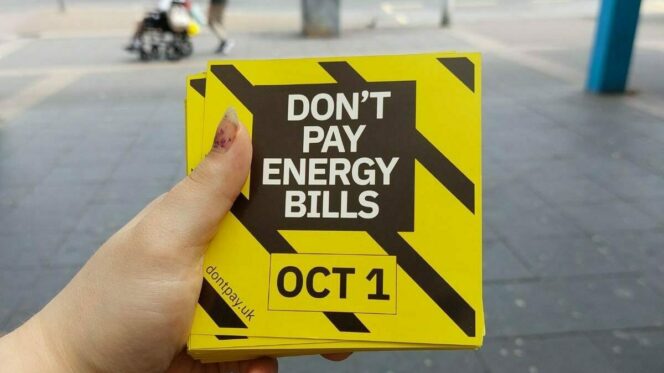

That is because the new prime minister inherits an economic situation without recent precedent. Investment bank Goldman Sachs has predicted inflation of 22% by early next year, while energy bills continue to rocket. We stand at the cusp of five quarters of economic contraction, as bad as the recession in 2008. Then there is the deepening social crisis, from average ambulance waiting times reaching an hour (the target is 18 minutes), to waterways being pumped with raw sewage a thousand times a day.

Worst of all for Truss, given the composition of the Tory electoral base, is the spectre of rising interest rates. Austerity under the Cameron premiership was possible because interest rates stayed low, along with inflation, giving a semblance of prosperity for just enough people. Should they even touch 5% next year, home ownership will fall further and the things that have so far satiated the middle class – business loans, home renovations and cars on credit – will evaporate.

This is all before mentioning the war in Ukraine, with Ben Wallace telling the Mail on Sunday that Putin’s ‘war on the West’ could last a decade. Or the fact that more than two-thirds of Tory MPs didn’t support Truss in late July. Given Johnson’s potential ambitions to return to front-line politics, and Sunak’s refusal to enter the next cabinet, internal divisions could quickly re-emerge.

Doomed to fail.

There is no recent precedent for a politician emerging triumphant against such adversity through sheer force of will. To suggest otherwise is nonsense.

The coalition tried to claim that a public debt of 60% was a national emergency (it is now 100% and climbing – though this is rarely talked about). But this was a confected crisis, done in league with much of the media because they were seemingly bored of Labour. Meanwhile Brexit, despite the gnashing of teeth, will be a slower process of divergence rather than a swift calamity.

The comparison to 1979, and the ascent of Margaret Thatcher, is more compelling. But while it’s true inflation stood at 10% that summer – the same as today – and the era was one of similarly high industrial tension, Thatcher inherited power at a tipping point with regards to consent for Britain’s economic model. She promised to dramatically change things. Truss, meanwhile, seems content to offer more of the same. Most importantly, Thatcher demonstrated her resolve through the trials of a general election. By contrast, Truss has just defeated Rishi Sunak, who would rather be in Palo Alto putting his Green Card to good use sipping frappes with Zuck.

Another major difference to 1979 is that long-term thinking has been absent in government for more than a decade. That holds for our growth model, energy policy and constitutional future. By contrast, the postwar arrangements against which Thatcher rallied had planning and foresight at their heart. Where Thatcher claimed the state did too much, today it does too little: Britain’s water companies, for example, haven’t built a new reservoir since privatisation 30 years ago.

Expect decisive action in 2022, then business as usual.

Faced with all of this, from popular discontent around the cost of living to potential rancour among her colleagues, it is critical for Truss to make an immediate, emphatic impression. This isn’t about cultivating an image (looking ‘prime ministerial’ as the London pundits like to say), but communicating policy that addresses problems. The Sunday Times has speculated on an emergency package ‘easily’ in excess of £100 billion, while the Mail quoted a Truss aide acknowledging they had to ‘hammer’ the energy companies to gain popularity. Elsewhere Team Truss has mooted a cut on VAT from 20% to 15%. That would reportedly save the average household more than £1,300 a year – although at a cost of £38 billion to the exchequer. A reduction to even 10% has been mentioned. In any case, dramatic, attention-grabbing changes could happen as soon as this month.

But alongside those decisive measures – and action on energy bills – Truss’s longer-term thinking is nothing more than a doubling down on a failed orthodoxy. We will be told how low tax, plus fracking, can save Britain. This discombobulating contrast to the extraordinary action we’ll see in the short term may please the party faithful, but it’s hard to see how it leads to rising real wages, addresses the housing crisis or cleans the country’s waterways.

For all the talk of the Conservative party being decimated at the next election, the party has an electoral floor as long as it can guarantee cheap mortgage borrowing and rising – or at least stable – house prices. Protecting property prices will therefore play a part in how Truss navigates the treacherous waters ahead, along with a massive intervention this winter and the use of fracking as a gesture towards energy independence (ignoring the reality: higher bills, compared to accelerating renewables and retrofitting homes).

All in all, what can we expect from Truss? Generous action now, Britannia Unchained later.

But dealing with the unfolding circumstances will probably prove beyond the powers of the prime minister. That is all the more likely given Truss starts the job with next to no political capital: more than half of British voters think she will be a poor or terrible PM, with little more than one in 10 expecting her to be good or great (‘great’ is just 2%). Most remarkable of all: less than half of Tory supporters believe she has the solutions to deal with the cost of living crisis.

In 1979 Thatcher promised painful, necessary medicine – a pledge which won her a mandate to govern. In 2022 the public is in no such mood. Austerity, then Covid, has destroyed any appetite for the kind of economic masochism that Truss, and her retinue, would like to inflict after this year. They ignore that at their peril.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.