To Avoid Another Pandemic, We Need to Eat Less Meat

Intensive animal farming is breeding deadly diseases.

by Jack McGovan

29 November 2022

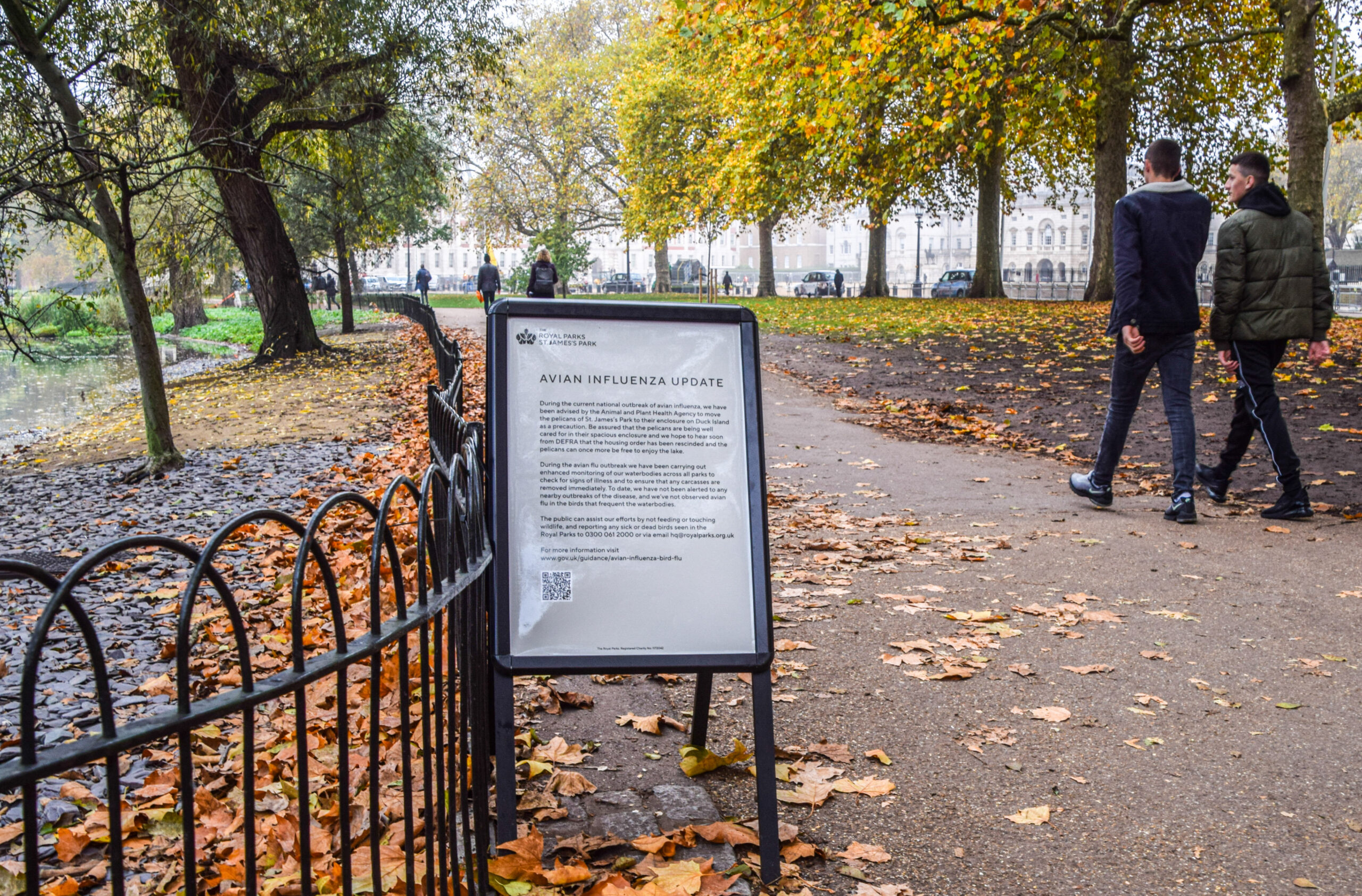

With Covid-19 in retreat, another virus is currently tearing through the UK, albeit with much less fanfare: bird flu. In fact, we’re in the midst of the union’s largest bird flu outbreak in history.

In an attempt to contain the virus before it mutates – with the potential to become a deadly human disease – the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) have implemented mandatory housing for all poultry, programmes deterring wild birds from approaching bird enclosures, and enhanced cleaning protocols. Consumers are feeling its impact via egg supply issues and a potential turkey shortage this Christmas.

Though human transmission of bird flu is rare – there have only been 868 confirmed cases since 2003 – the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control says that the H5N1 strain, which is currently circulating in the UK, has a mortality rate of 50%. On 3 November, it was reported that two poultry workers in Spain were infected with the virus – the second known cases of human transmission in Europe since 2003.

Devi Sridhar, a professor in public health, writes in The Guardian that a “mutation that makes this virus circulate more easily between humans is possible”, and the more chances the virus has to mutate, the “more likely it is [that] a dangerous strain will emerge that could set off the next pandemic.”

These prevention efforts also mean examining the causes of virus spread. So far, the current outbreak is being blamed on wild birds. In a document released to press in early November, Defra stated that: “The main route of infection into our poultry and captive birds has been through direct or indirect contact with wild birds”. A similar update from the UK Health Security Agency also pointed to wild birds as the preeminent flu carriers. In reality, the H5N1 strain emerged in commercial geese in Asia in 1996.

“It is undoubtedly the case that bird flu can be spread by migratory birds,” says Sam Sheppard, a professor in microbiology at the University of Oxford. “But I don’t think that the underlying research yet supports exactly the narrative that’s being told.”

A troubled industry.

In 2006, around the time that bird flu became a global virus, an article in The Lancet implicated the poultry industry in the spread of the disease, as the pattern of outbreaks followed major roads and railways rather than migratory flight paths. In 2005, Mike Davis, author of ‘The Monster at Our Door’ which examined the spread of bird flu, told a reporter: “A Thai-based [livestock] firm called C.P […] was directly involved in the Thai government’s cover-up of the initial outbreak of avian flu [last year]”.

“The important thing here is to think about the impact of intensive agriculture on the emergence of new variants,” says Sheppard. Globally, the animal agriculture industry occupies more land than forests, and over 70% of animals are factory farmed. In the UK, 94% of chickens are intensively farmed, though half of eggs sold are free range. Worldwide, we keep more birds as livestock than there are wild birds, so there’s a larger number of hosts available for viruses on farms, giving more chances for mutations to occur and create a highly infectious strain. Cramped, stressful conditions promote the spread of disease, and this phenomenon has been seen in pigs too.

Government mismanagement of animal disease outbreaks doesn’t help either. A House of Commons Committee report published at the end of October found that “the UK’s main animal health facility at Weybridge has been left to deteriorate to an alarming extent” due to inadequate management and underinvestment by Defra, impacting the facility’s ability to effectively respond to disease outbreaks.

While less intensive agriculture might seem like an easy solution to stopping the spread of viruses, that can lead to disease emergence through different mechanisms. More land is required to rear animals without factory farms, meaning more deforestation and habitat destruction to maintain the same level of animal product consumption as in our current system. This subsequently leads to a reduction in biodiversity which is linked to the emergence of diseases from wild animals. Only one solution tackles disease emergence across the board: reducing animal product consumption.

Avoiding the answers.

The UK government is strongly averse to that strategy, though. Instead, they’re turning to tech.

One solution the government seems to be focusing on is breeding bird flu resistant chickens as part of their Genetic Engineering Bill. The bill, currently going through the House of Lords, will remove plants and animals produced through precision breeding technologies from regulatory requirements applied to GMOs. This essentially means that technology can be used to aid and speed up the breeding process.

Sheppard isn’t opposed to technological solutions like gene-editing. He says, however, that the government’s plans would only treat flu symptoms; birds could still carry the virus asymptomatically. “We could vaccinate for bird flu and that would help,” he explains, but would require a booster programme and wouldn’t confront the increasing problem of antibiotic resistance – exacerbated by livestock farming.

Reducing overall consumption of animal products is the only real long-term option to confront animal disease emergence, say experts. “If we all were vegetarian, we wouldn’t have a problem with livestock related diseases,” says Sheppard. “[Though] it’s not up to me to tell people what to eat […] but less meat, of higher quality [is an option]”. This would mean higher prices for consumers to cover the costs of stricter biosecurity measures, as well as a noticeable reduction in animal product consumption. But this is a western focused strategy, Sheppard admits.

The UK government seems unlikely to push for less meat consumption. In the run-up to COP26 last year, a research paper was uploaded to a government website recommending a reduction in meat consumption. This is because the livestock industry is responsible for around 32% of global greenhouse emissions and alone occupies more land than forests do globally. It was swiftly deleted and followed by a statement that the government “has no plans to dictate consumer behaviour in this way.”

A refusal to tackle excessive meat consumption is a global problem. At COP27 this year, reducing meat consumption wasn’t on the agenda. Instead, one proposed solution included changing cattle feed to reduce the methane content of their burps, which has been debunked. In comparison to COP26, more than twice as many delegates linked to agribusiness interests were at COP27.

The government’s refusal to confront the problems of animal agriculture has led to a situation where the UK public misunderstands the costs. British adults were found to blame the wildlife trade more than factory farming for infectious disease spread, with those “highly committed to eating meat” wilfully ignoring the risks of intensive farming.

Activists take the initiative.

“The government hasn’t just failed to reduce animal agriculture, it has actively promoted it through subsidies, paid advertising and direct market manipulation,” says Joel Scott-Halkes, campaigns director of RePlanet, an environmental network.

During COP27, RePlanet launched their ReBoot Food campaign, calling for a move towards precision fermentation – the use of bacteria to grow food in vats. The organisation is lobbying the government to help animal farmers transition to plant-based production and to make precision fermentation open source, to prevent corporate control.

Another initiative launched during COP27, Beans is How, is aiming to double bean consumption by 2028. Similarly, the Plant Based Treaty are advocating for a shift to plant based wholefoods like beans, lentils, and tofu. While there are differences between different groups fighting for an end to excessive animal farming, there is at least a consensus that the industry must be stopped.

“It’s time for the government to think of animal farming as previous governments thought of smoking,” says Scott-Halkes. “Is it deeply embedded in our culture and supported by the majority of the population? Yes. Is it slowly killing us? Also yes. So the course of action needs to be the same.”

Jack McGovan is a writer based in Berlin, covering politics and climate.