Students Are Occupying Schools and Universities in Protest at Climate Chaos

In November, in one of the oldest courtyards of the University of Barcelona, something strange happened. Tents were erected. A banner was strung up in a stone archway. For seven days, students led workshops on movement-building and political struggle. At night they ate, talked and sang together.

The students had two clear demands of their university: that it cut ties with fossil fuel companies, and that it introduce a compulsory module on the climate crisis.

“They [the university management] didn’t want us there,” Gil, 21, tells Novara Media. “We weren’t able to predict what was going to happen.”

The students stayed put, and before long, the university caved to one of their demands. From 2024, the University of Barcelona will be the first in the world to run a mandatory climate course for all students.

“This was a big achievement,” Gil argues. “It was a beautiful experience, and it pulled us all together.”

School strike 2.0?

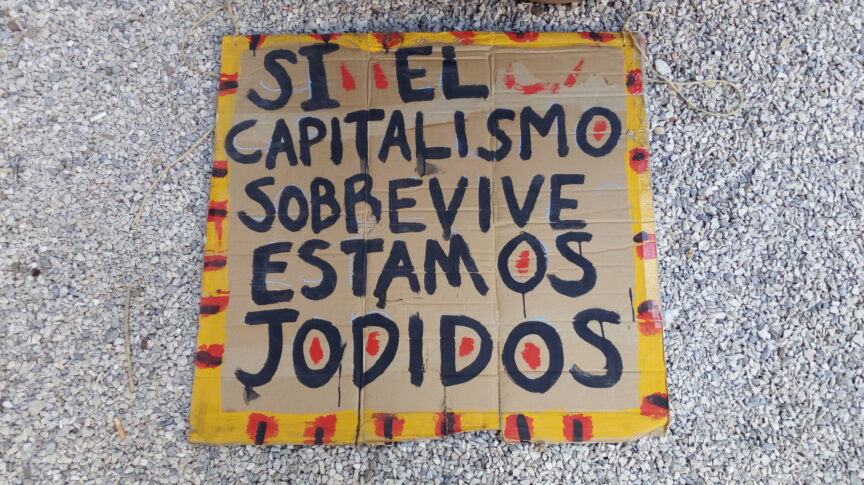

The occupiers in Barcelona weren’t alone. Over the last few weeks, students around the world – particularly in Europe – have staged occupations at their schools and universities. In Lisbon, highschoolers blocked school entrances and glued themselves to doors. In Vienna, hundreds of university students occupied a lecture theatre. In Granada, activists camped in the corridors.

The group behind these protests is End Fossil – an international, youth-led coalition intent on taking down the fossil economy.

Matilde Alvim, a 21-year-old student from Lisbon and co-founder of End Fossil, explains that the movement was borne out of frustration with the declining momentum of the ‘school strike for climate’ which, at its peak in 2019, drew millions of young people out onto the streets and forced climate breakdown onto the global agenda.

“We were too comfortable with what we were doing as a movement,” she tells Novara Media. “We weren’t pushing ourselves to think, like, ‘is this what this climate emergency demands? Or are we just pretending we’re doing something?’.”

Towards the end of 2021, Matilde and other strikers started having conversations about how to “radicalise the youth movement”. For inspiration, they looked to radical youth movements throughout history: the student occupations in France in May 1968, the Penguin Revolution in Chile in 2006, and the Primavera Secundarista in Brazil in 2016, amongst others.

End Fossil launched in March this year, with a wave of occupations announced for between September and December. While it cohered around a tactic – occupying schools and universities until at least some of its demands were met – it encouraged students to establish their own demands of their universities, from rejecting funding from fossil fuel companies to calling on the government to take the fossil fuel industry into public ownership.

Activists see a number of strengths to occupations over strikes. If, as one put it, the strategy of the strikes had essentially been “to go out into the streets and beg our leaders to not kill us”, with occupations, the strategy is to “disrupt the normal functioning of society”.

End Fossil had hoped for between 50 and 100 occupations this autumn. But while in some countries they achieved significant wins – or at least high levels of disruption – elsewhere, things didn’t take off to the same extent. In Britain, only two occupations took place – one at the University of Leeds, the other in Cornwall – both of which went largely unnoticed. Why?

First attempts.

Hannah, a 22-year-old student at Leeds, and Ethan, a 21-year-old student at Exeter, first heard about the plan for occupations via Zoom over the summer. They each pulled together a small group of would-be occupiers – the latter in collaboration with students at Falmouth University, with which Exeter shares a campus – and within a few months, they were ready.

Getting the occupations started was relatively easy. “We just walked into the building with all our bags and our masks,” says Hannah. “We had someone run down to the lower door and lock it, and we blocked the top one.” Once the doors were secured, the Leeds students invited others to join them.

Both the Leeds and Exeter occupiers found the wider community was generally supportive. Over 100 students joined a rally in support of the Leeds occupation, which was also backed by local trade unions. Meanwhile, in Exeter, students tried to push past university security guards to join the occupation.

University management, however, was much more hostile. At Leeds, students received a letter warning that occupiers would be expelled. “People were really concerned about this,” says Bear, 20. “Half the group left the day after.” At Exeter, students were threatened with a court order. “If that had happened, I think everyone who occupied would have been brave enough to take that on,” says Phil, 22.

Neither came to pass, however. The Exeter and Falmouth students ended their occupation after both universities agreed to hold public assemblies on the students’ demands. The Leeds occupation ran out of steam – although once the occupation was already over, the university promised to hold an event on “sustainability”.

Though their victories were only partial, both groups of students think their occupations achieved important things. Firstly, students felt there was a valuable prefigurative element to the occupations. Whilst the climate strikes were about demanding a different kind of world one day every few months, the occupations were about bringing that world into being.

“You’re not just occupying as in taking a space,” says Ethan. “You’re also, like, creating a new space sort of modelled on the change that you want to make. For example, all the decisions made during the occupation were made unanimously.”

Secondly, both groups feel they’ve really changed the conversations at their universities – and have a much stronger foundation on which to build.

“There’s a real air of change on campus that sprung from the occupation,” says Phil. Hannah senses a similar shift at Leeds: “We mobilised a lot of people outside the occupation, and we’ve got a really consolidated local group,” she explains. “We’ve now got a community of people who will get involved in lots of other stuff.”

Still, the fact remains that only two universities in Britain held occupations. This is no doubt partly because there’s a higher barrier to entry with an occupation than a strike – particularly with the threat of expulsion and legal action. “It’s definitely a step up in the youth-led climate action space,” Ethan explains. “You need a real strong team to, like, go into resistance like that.”

Another reason for the lack of take-up may be that students at universities including Sheffield and Manchester staged other occupations during the pandemic, meaning there was perhaps less appetite for more so soon. It could also be that most universities don’t have a recent history of occupations. “Most people just can’t get into that straightaway,” Hannah argues.

Activists also wondered whether the fact that the UK youth strikes disintegrated, while movements across Europe stayed active, made it harder to drum up interest in the occupations. But now they’ve been done, the Leeds and Exeter occupiers hope the tactic will catch on. Indeed, they’re keen to make this happen by actively pitching the tactic to others and organising skillshares on how to stage occupations.

“It’s definitely something I think we could mobilise a lot more people for next time around,” says Hannah.

A taste of disobedience.

Matilde agrees that the number of occupations this time around isn’t a cause for despair.

“The truth is that the climate strikes didn’t start on 15 March 2019,” she argues. “There was also a strike in 2018, but it wasn’t as known about. Sometimes things need a prototype, so people can see what it looks like. And then from that prototype, you create energy to grow.”

After a period of evaluation – and some much-needed downtime – End Fossil is hoping to hold an international congress in the new year to discuss how to build the movement into something truly disruptive. Matilde says we could then see a second wave of occupations in the spring.

As for Hannah and the other UK occupiers, there’s already interest in another occupation.

“I think what’s really important with this stuff is giving people a first taste of disobedience,” she argues. “You realise that the authority we see is just a mirage. You just kind of have to push the line a little bit, and you’ll find it gives way.”

Clare Hymer is head of articles at Novara Media.

Sam Knights is a climate justice activist and the editor of This Is Not A Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook.