We Tried to Shut Down Drax Power Station. Spy Cops Stopped Us

Around 2am on the morning of 26 August 2006, I found myself lying in a ditch with 20 other people in the countryside near Selby, North Yorkshire. We were hiding from a car that had pulled up several fields away. It was my job to lead this group from our drop off point several miles away, through the pitch-dark night, to a field that was to be squatted for the first ever Camp for Climate Action.

Some comrades and I had recced the route a few nights before. I had a map, a torch, and a general idea of the direction we should go. So once the car moved off, so did we. The timing and secrecy were important. We had to reach our destination and secure the site just before the arrival of a lorry carrying the equipment we needed: tripod lock-ons, fencing, marquees and more. As the first light of dawn cracked the horizon, the mission was accomplished. We built our nascent camp, and a team set off to visit the farmer whose field we were in. He accepted the envelope of money they offered him as rent. Now the police couldn’t shift us.

This memory came to mind a few days ago when I saw Drax power station back in the news. In 2006, Drax was the largest coal powered power station in Europe and the single biggest emitter of carbon across the whole continent. We were there to protest Drax, and if we could, to shut it down.

In 2006 I helped to establish the first climate camp near Drax. That week there was a failed attempt to symbolically shut down the power station. Four years later we discovered the reason for the failure. Two activists I knew were revealed as uncover cops. This is their legacy. https://t.co/NfXS0zWqCh

— Keir Milburn (@KeirMilburn) October 4, 2022

The camp carried on for ten days, but the 600 people it attracted were far outnumbered by police brought in from several forces. It proved impossible to approach the power station itself. While we had garnered some favourable media attention, we needed something more spectacular if we were to spark the kind of social movement that climate change demanded. So on 2 September, groups of trusted activists filtered out of the camp and made their separate ways to a social centre in Bradford. Once there, we went over the plan for another night operation. The aim was to get a group into the power station and close it down. By occupying precarious positions high off the ground, we thought the occupiers could hold out for several days and garner worldwide attention.

This time I had a driving role in the operation, but as we approached the drop-off point, it was obvious we’d been rumbled. Police vans dotted the route. When the team reached the power station fence, they were surrounded and pushed back. One activist from Nottingham, Mark Stone, was severely beaten by police officers causing long term injuries to his back.

Robbed of our moment, the climate camp movement was forced to build the hard way with a series of annual camps over the next four years. A camp at Heathrow in 2007 was followed by one at Kingsnorth power station in Kent in 2008. It was there that hostile policing reached a whole new level. I arrived with my eight-year-old daughter just as a group of riot police pushed their way into the camp, shields and batons in hand. I approached an officer and said: “Look mate, are you about to start cracking heads because my daughter is over there, and I’m scared for her.” He turned to me and answered: “Do I look like the sort of person who cracks heads?” I replied: “The way you’re dressed, you can’t do anything else.” Soon, the camp attendees surrounded the patrol, hands in the air, shouting at the police to leave. Eventually, they were forced to do just that. I remember my daughter asking: “Are we meant to be free here, dad?” I said we were, and she started cartwheeling down the hill.

The police broke numerous laws that week and were forced to pay out thousands of pounds in compensation, but the repression of protest continued to ramp up. The 2009 climate camp in the City of London was viciously attacked by riot police and street vendor Ian Tomlinson was killed by a police officer as he tried to leave the protests. His death prompted a scandal around the police, which rolled into further revelations about undercover policing.

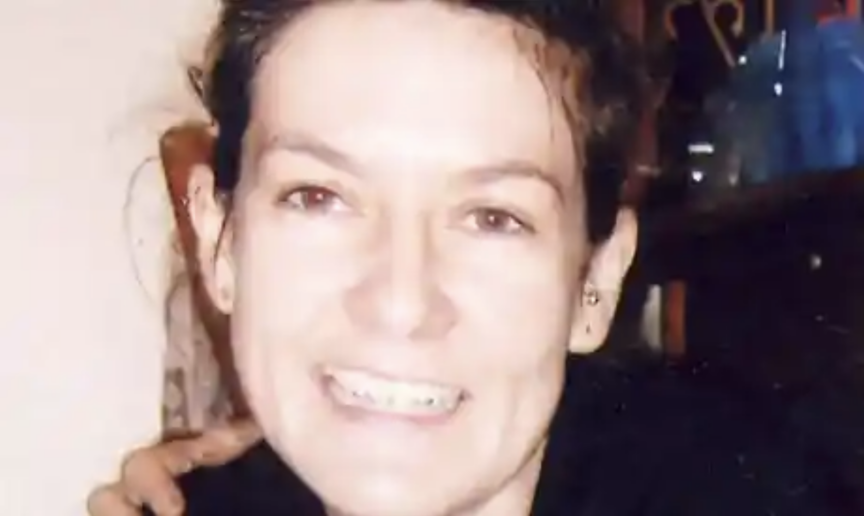

In January 2011, I was at a meeting in Manchester with some climate camp veterans. We opened the paper and there was Mark Stone, now revealed to be undercover police officer Mark Kennedy. We already knew of this revelation. Kennedy had been confronted by activists in October 2010 after they’d found his real passport, but it was still a shock to see him pictured in his police uniform. The frenzy that followed uncovered a whole network of undercover cops across the left – a scandal that led to the ongoing government spy cops inquiry.

Among the first to be outed was Lynn ‘Watson’, whom I’d known for five years. Our mission to squat the site of the 2006 camp had departed from Watson’s house in Leeds. This means at least some in the police knew our intentions in advance. So, did I yomp across the dark fields of Yorkshire in vain? I don’t think so. Our efforts to use secrecy and instil a security culture within our organising meant the police were reluctant to act on the information they received for fear of revealing their sources. Indeed, this eventually led to Kennedy’s downfall: a 2009 preemptive raid to prevent the occupation of Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station cast suspicion onto Kennedy which was later confirmed. This was no shock to me. A friend had told me of his suspicions about Kennedy several years before, but we kept this close to our chests. Premature accusations and the distrust they cause can be far more harmful to movements than the actions undercover officers undertake.

In 2011, the climate camp network decided to disband. The undercover cops had certainly hampered the growth of the climate justice movement. Throughout this whole period, the police acted as the armed wing of the fossil fuel companies, paying scant regard to the legalities of their own actions. But this wasn’t the main reason for the climate camp’s dissolution. In truth, times had changed. The financial crash of 2008 had transformed the political environment, and by 2011 ‘generation left’ was being born in the camps of Occupy and occupied lecture theatres of the student movement. History contains moments of rupture after which movements must change shape and recompose themselves. The climate camp disbanded to allow that to happen. I suspect another such moment is in the post right now.

Watson and Kennedy were undercover for six and seven years respectively. When we include the costs of their support staff, the price of their deployment runs to several million pounds. Of course, there were other prices to be paid. The sense of betrayal when friends are revealed not to be who we thought they were is nothing compared to the experiences of the many women manipulated into sexual relationships by undercover police officers. Some cops even fathered children with women they were paid to spy on. There are other legacies too. These can be seen in the floods of Bangladesh, the forest fires in California and the other extreme weather events occurring with increased frequency.

But what of Drax? In 2012, some of the generating units at the power station were converted to burning biomass. On that basis, Drax now claims to produce 12% of Britain’s renewable energy and has received £6bn in green energy subsidies for its trouble. This week an investigation by Panorama has implicated the company in cutting down ancient forests which hold huge quantities of carbon, making a mockery of their renewable claims.

This is just the latest in a long list of scams and frauds plaguing the schemes of green capitalism, and it will keep happening while energy production remains in private hands and so is driven by the bottom line. We need to bring our key infrastructure under democratic public ownership, and the only way to get there is to bring business as usual to a halt. The climate campers were right. If we are to keep the planet as liveable as possible, we must spark a climate justice movement bigger than we’ve ever seen before.

Keir Milburn is the co-director of the Abundance think tank. He is also the author of Generation Left (2019) and Radical Abundance (forthcoming in 2025), and co-hosts Novara Media’s #ACFM podcast.