No Job, No Rent: I Was a Full-Time Militant in the Nineties

There are many distinctions between political generations. None is more important than how material conditions underscore the opportunities and limitations of their activity.

I entered into radical politics in the late 1990s. I was inspired by a number of shifts: the then burgeoning anti-roads movement, whose innovative use of direct action was fast scuppering the Tories’ ecologically destructive road building scheme; the growth of rave culture and the free party scene. I was also motivated by opposition to new forms of legislation that sought to criminalise these phenomena – and by extension further criminalise and curtail the activity of urban squatters, hunt saboteurs, traveller communities, football fans and striking workers. The threat this legislation presented to each group only cemented the bonds of solidarity we felt for one another. Indeed, this solidarity provided the basis for the anti-capitalist ‘days of action’ that made international headlines in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

During this time, I existed in a radical counterculture predicated on direct action, political and cultural experimentation and a resistance to waged labour. The various projects that constituted this scene were based on ideological commitments, volunteerism and free association. If you didn’t like the direction of a particular project, you could go away and start your own. As such, the early 1990s saw an explosion in self-organised and militant anti-capitalist activity, ranging from radical ecology to anti-fascism and beyond.

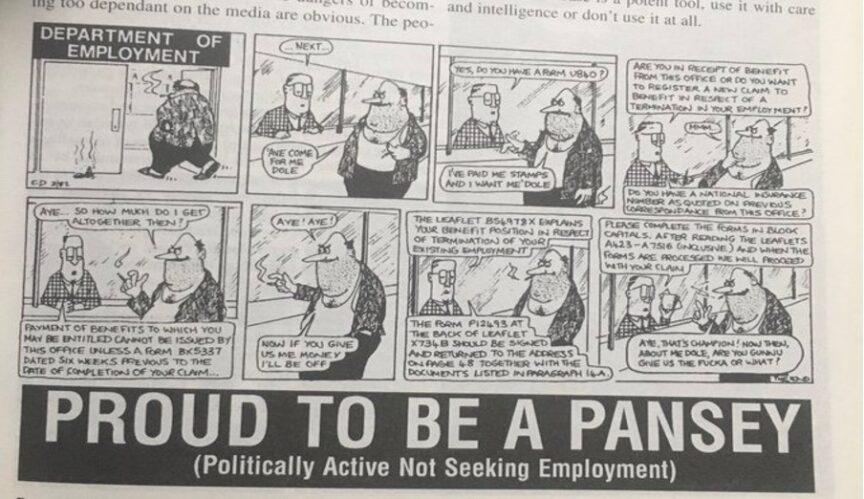

Two things made this possible. The first was the dole. Access to unemployment benefits meant that if we wanted to dedicate our lives to full-time activism, there were the financial means to do so. Of course, we weren’t the first generation to conceive of the dole as a social wage. By the time I entered the scene there was already a long precedent for that, stretching back to the late 1960s at least. But so prolific was the lifestyle within my generation it was rumoured the Department for Work and Pensions had introduced a new category of dole claimant – the ‘pansey’ (Politically Active Not Seeking Employment) – a badge many of us wore with honour.

The second was weaker anti-squatting legislation. In the late 1990s, London was still heavily populated with squats. This provided us with cheap housing, as well as spaces in which our ‘self-organised’ politics were lived and our social bonds re-enforced.

A week might look something like this. On Monday night, there’d be a cross-movement planning meeting in a squatted flat in Borough for an upcoming May Day ‘day of action’. On Tuesday, a meeting of local tenants and squatters in an occupied warehouse in Whitechapel about how to resist rent hikes. On Wednesday, a mid-week ‘squatters supper club’ organised at a friend’s flat in Lambeth, where we socialised and swapped information about ‘empties’. On Thursday, a film screening and discussion in support of the Zapatistas at a mate’s squat in Hackney. On Friday, a benefit for German anti-fascists featuring top European squatter bands in an abandoned pub. And on Saturday night, a large warehouse rave and benefit raising funds for… you get the picture.

And those were just the evenings. Free from the bondage of work, our days were spent producing radical bulletins and newspapers, flyposting local estates, organising protests and direct actions, frequenting radical bookshops, meeting comrades for informal gatherings and cooking collective meals. There were plenty of entry points through which younger activists could get involved in ‘the movement’, and, without the need to work or pay rent, were able to reproduce their lives as full-time militants.

By the time the 2010 student movement was in full swing, changes to both the dole and tighter anti-squatting legislation made this lifestyle increasingly difficult. However, the self-organised politics of London’s radical direct action movement nonetheless shaped the concerns and sensibilities of this generation, many of whom would, in 2015, redirect their efforts and resources to supporting Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party leadership bid.

The turn toward institutional politics heralded by Corbynism was seen by many within the socialist left as a means to escape the narrow, ‘noble heroism’ of direct action and political minoritarianism. While this may be true, one can’t help but think this turn – coupled with the near collapse of the dole and squatting – has, in many ways, had a negative impact on both the political imagination and political opportunities presented to younger activists.

If you’re a young militant today, what are the opportunities to dedicate your life to full-time anti-capitalist activity? If you were turned on to politics during the Corbyn years, what are the means by which you can live out your ideological commitments? Clearly, in order to be a full-time militant in 2023, you need a wage. And in the face of crippling rents and a cost of living crisis, that wage needs to be enough to make ends meet, with many people working multiple jobs. Little time remains for radical volunteerism, and as such, student campuses are one of the few spaces in which militants are able to dedicate significant time to political activism.

Another option for many young radicals is to get a paid organiser role within a professional NGO or trade union, with all the conservatism, compromise and ‘towing the line’ that this entails. After all, you’re less likely to challenge the political direction of a campaign if it’s also the means by which you reproduce your life. What’s more, this trend also shapes politics itself, with many young radicals joining such campaigns not because they feel these are the most important political projects to get involved with, but in the hope they too will be offered the next organiser job.

In the absence of the resources and spaces that allow people to come together, develop projects and experiment with ways to act collectively, the radical left has largely retreated to the online world. Here, it maintains its ideological commitments, yet broadly fails to turn these commitments into real-world action. By contrast, thinking through the means by which younger militants can create, grow and then regenerate their own projects – and on their own terms – is vitally important if we want to overcome the left’s malaise and stagnation. Indeed, how to achieve this remains the most important question of our time.

Seth Wheeler is a writer and activist. He is the contributing editor of ‘In and Against the State’ (2021 Pluto Books).