Banning Puberty Blockers Won’t Stop Young People Taking Them

It’ll just make it riskier.

by Vic Parsons

15 June 2023

On 9 June, NHS England announced it plans to stop providing puberty blockers to young trans people who want them, unless they take part in a clinical trial. The decision came in a report setting out the future of healthcare provision for young trans people in the wake of NHS England closing Gids – the only gender clinic for under-18s in England and Wales – saying there’s “not enough evidence” puberty blockers are safe or effective to continue prescribing them.

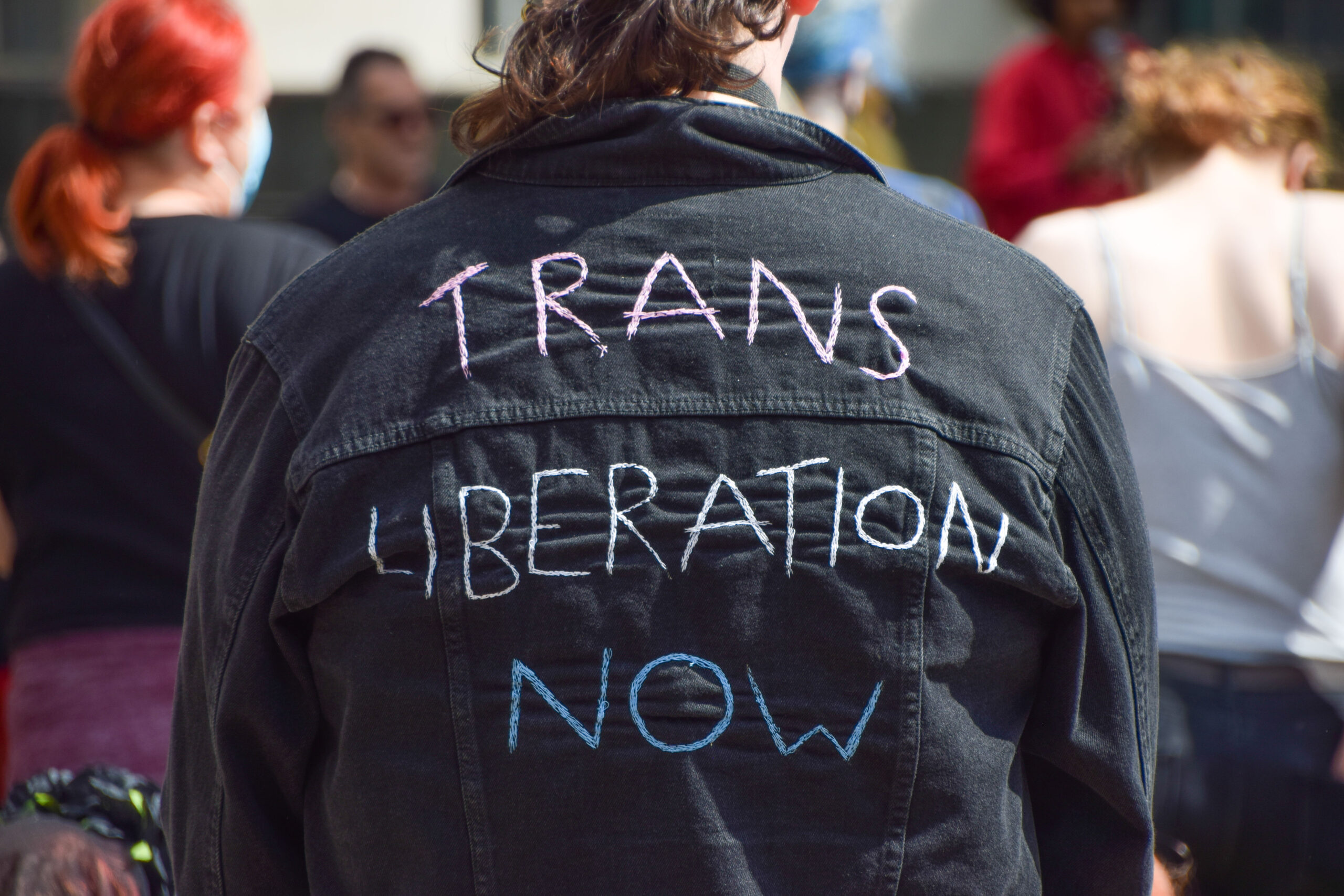

This decision to take away young trans people’s bodily autonomy is situated in a global context of rapidly escalating transphobic moral panic and rising fascism. Indeed, rightwing groups lobby against trans healthcare and abortion access simultaneously, with hard-won rights for women and LGBTQ+ people being destroyed by conservative ideals of women as child-bearers and queer people as deviants.

In the UK, access to puberty blockers has been under attack for years, from transphobes branding them “experimental” and “dangerous” to the infamous Keira Bell court case in 2020 that attempted – and initially succeeded – to stop them being prescribed on the NHS. But despite this laser focus on puberty blockers, very few young trans people actually access them. During Bell’s case, it was revealed that in 2020-2021, just 131 young trans people across England and Wales were prescribed puberty blockers by the NHS. The attention given to puberty blockers by the media ignores the fact that many young trans people don’t want to take blockers at all. By medicalising transness, the media stigmatises us and tells young trans people that their identity is tied to taking puberty blockers – and that they can’t have them.

Unsurprisingly, NHS England’s decision flies in the face of abundant evidence that transitioning is good for trans teens. Moreover, outside the realms of medical research into transness, it seems obvious that accessing the healthcare you want at the time you want it is better than being denied it, or forced through a gruelling and pathologizing years-long process to get it. That’s not to say that all young trans people want to or should take puberty blockers – only that the option should be there for those who do, just as the availability of free and safe abortions for people who want them doesn’t prevent others from having babies.

There are many implications of NHS England’s decision. Some young trans people will no doubt enter long-running clinical trials, trading their privacy for healthcare. Young trans people who want puberty blockers and have supportive, wealthy parents will get them through private trans healthcare providers, with professional oversight. Those with supportive but poor parents might buy puberty blockers from unregulated online pharmacies – cheaper, but riskier. And for young trans people without supportive parents (more than four in ten trans and non-binary people have been abused or rejected by close family because of their gender identity), the increase in stigma associated with puberty blockers compounds their inability to safely access them.

Finally, just as people in Ireland long travelled to the UK for abortions, it’s also likely that some parents with trans kids will travel abroad to access trans healthcare, or move to friendlier countries. Trans Rescue, a non-profit that helps trans people flee countries where it’s unsafe to be trans, doesn’t yet support people to leave the UK – but does advise making an escape plan.

The NHS England report instructs doctors to refer young trans people who’ve accessed puberty blockers through non-NHS routes – online pharmacies or private healthcare providers – to local safeguarding teams, which include the police. This quasi-criminalisation of puberty blocking medication for all except the few who get onto the clinical trial is a worrying development.

Making puberty blockers harder and less legal to access for the hundred or so young trans people each year who want to take them won’t stop them wanting and trying to get them. Criminalisation doesn’t work: sex work is criminalised in the UK, which just means women are forced to work in more risky and dangerous environments; abortion is criminalised, yet people who need an abortion will still procure one. This week, a 44-year-old mother of three, Carla Foster, was jailed for 28 months for having an abortion after the legal time limit – a tragic case highlighting why abortion, like sex work, must be decriminalised. Forcing people to go through illicit routes doesn’t stop them, or make them safer.

The NHS England report also states – bizarrely – that gender dysphoria usually stops once puberty is reached, an argument undermined by the existence of hundreds of thousands of trans adults living in the UK, many of whom experience gender dysphoria. Studies show that at least 90% of people who come out as trans when they’re young remain trans into adulthood, with transphobia and family rejection often major factors for the 10% who do detransition. By contrast, 42% of UK marriages end in divorce. Where’s the clinical trial testing the sanity of marital wannabes?

Research shows the benefits of transition for trans people. In 2018, Cornell University looked at 55 studies of trans healthcare over two decades and found 51 concluded that transitioning – be it socially, medically or legally – improves trans people’s overall wellbeing. A 2022 US study of 104 young trans people found that those who could access gender-affirming healthcare were 60% less likely to be depressed and 73% less likely to be suicidal than those who couldn’t. Another recent US study found that trans people who wanted but didn’t get puberty blockers as teenagers were 1.5 times more likely to be mentally distressed and 1.2 times more likely to have been suicidal than trans people who wanted and got puberty blockers.

Trans youth who want puberty blockers badly enough will procure them from sources other than the NHS. Like Foster, they’ll just do so outside of what’s legally permitted. That hasn’t stopped those in need of healthcare before – and there’s no reason to think it’ll do so now.

Vic Parsons is a freelance journalist.