Mental Health Diagnoses Are Capitalist Constructs

Your experience is real. But the way we label it is influenced by systems of power.

by Micha Frazer-Carroll

24 July 2023

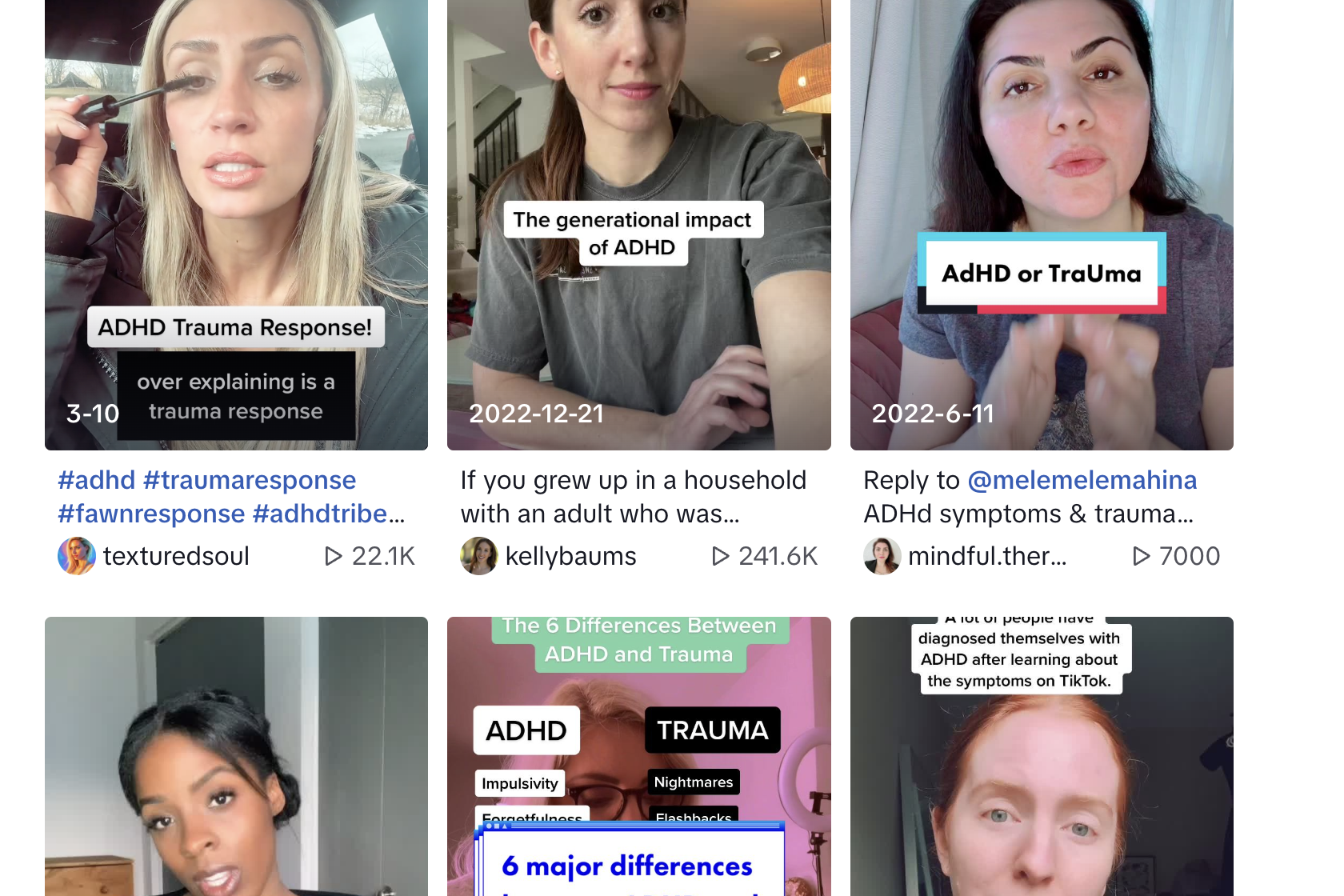

TikTok teens diagnosing themselves with autism and ADHD, rising depression rates, an ever-growing awareness of trauma and an ongoing dispute around the validity of conditions like borderline personality disorder (BPD): psychiatric diagnosis is a hot topic right now. It seems like there’s a general anxiety about diagnoses that relate to our minds, as if we instinctively understand that certain categories are political, and precarious. But with discussions about diagnosis usually restricted to debating whether specific categories are “real” or “fake”, “overdiagnosed” or “underdiagnosed”, “good” or “bad”, we often lose sight of the fact that diagnosis is a system of power, which is closely linked to capitalism and the state.

Mental and physical diagnoses aren’t objective facts that exist in nature, even though we usually think of them this way. While the experiences and phenomena that fall under different diagnostic categories are, of course, real, the way that we choose to categorise them is often influenced by systems of power. The difference between “health” and “illness”, “order” and “disorder” is shaped by which kinds of bodies and minds are conducive to capitalism and the state. For example, the difference between “ordinary distress” and “mental illness” is often defined by its impact on your ability to work. The recent edition of the DSM, psychiatry’s comprehensive manual of “mental disorders”, mentions work almost 400 times – work is the central metric for diagnosis.

When we look across history, it becomes even more obvious that diagnosis is tied to capitalist metrics of productivity: certain categories of illness have come in and out of existence as the conditions of production have changed. In the 19th century, the physician Samuel A. Cartwright proposed the diagnosis of “drapetomania”, which would describe enslaved Black people who fled from plantations. While we might think of drapetomania as a historical outlier among “true” and “objective” diagnoses, it is underpinned by the same logic as other diagnoses: it describes mental or physical attributes that make us less exploitable and profitable. In the 1920s, medical and psychological researchers became interested in a pathology called “accident-proneness”, which was applied to workers who were repeatedly injured in the brutal and dangerous factory conditions of the industrial revolution. Dyslexia, a diagnosis I have been given, also didn’t emerge until the market began to shift from manual labour towards jobs that relied on reading and writing, when all children were expected to be literate. Despite having problems with reading, I understand that in a world where reading and writing weren’t so central to our daily life, there would be no need to name my dyslexia, no need to diagnose it.

As a system of state power, many of us rely on diagnosis to get the material things that we need to survive in the world. When illness or disability interferes with our ability to work, we often need a diagnosis to justify our lack of productivity – and for some, diagnosis is the necessary pathway to getting state benefits. If we want to get access to medication, treatment or other healing practices provided by the state, diagnosis is also the token that we need to get there. This is made all the more complicated by the fact that doctors have the power to dispense and withhold diagnoses, regardless of our personal desires. When it comes to psychiatric diagnosis, most of us know someone who has had to fight or wait for years for a diagnosis that would improve their quality of life – particularly in the realm of autism, ADHD and eating disorders. The internalised racism, sexism, classism or ableism of doctors often gets in the way of our ability to access the diagnoses that we want and need. Then there are those of us that are given diagnoses that we reject, a process that we also have no say in. I have friends who have had to battle professionals to get, for example, a diagnosis of BPD taken off their medical records, because the diagnosis has severely negatively impacted their experiences within mental health services. In the sphere of psychiatric diagnosis, these issues are all the more pressing considering that there is no blood test, brain scan or other physical measure to determine diagnosis – they are entirely socially decided by professionals who hold power over us.

When we understand that psychiatric diagnoses are constructed, contested, and aren’t grounded in biological measures, the idea of “self-diagnosis” starts to feel less dangerous or controversial. Self-diagnosis is grounded in the idea that, while the institution of medicine may hold useful technologies and expertise, we also hold valuable knowledge about our bodies and minds. I know many people who have found solace and respite in communities for various diagnoses, even if they don’t have an official diagnosis from a doctor. These spaces, which respect the wisdom offered by lived experience, can be valuable forums of knowledge-sharing and solidarity. Self-diagnosis also pushes against an oppressive diagnostic system that is so centred around notions of productivity. For example, I have friends who have been denied a diagnosis of depression because they are seen to be “high functioning” (meaning that they are still able to work). For these people, claiming depression can feel like a way of affirming their experience of distress, even if it doesn’t impact on their productivity. Similarly, many autistic communities are reshaping the historically pathologising concept of autism, and reclaiming it for themselves. Their notions of diagnosis actively subvert psychiatry’s approach – because they centre the idea that people themselves should be able to accept or reject diagnoses as they see fit. When we think about self-diagnosis, it’s important to remember that most forms of diagnosis actually involve some element of self-investigation already – we all have experience of noticing, monitoring and researching our symptoms before we even set foot in a GP’s office.

Moving beyond divisive debates about diagnosis involves acknowledging the extent to which diagnosis is shaped by systems of power. Diagnosis isn’t an adjective (something we are) or a noun (something we have), it is a verb – an active process that is always moving, always serving an end. It can be wielded by the state in ways that are extremely harmful, but we can also break it apart and use it in ways that are liberating for us. In thinking about a different way of doing diagnosis, I want to dream big, and start with a utopian mindset. Would diagnosis matter so much in a world where all people and patients had more power – one where we did not have to constantly prove ourselves to employers, to medical professionals and to the benefits system to get our fundamental needs met? A system of social organisation in which healthcare and other healing processes centred informed consent, rather than medical gatekeeping? One that valued life over bureaucracy? Could we create a world where we don’t only describe our bodies and minds against the metric of profit? This future is uncertain and could take a number of forms, but it must be one where diagnosis can never again be the difference between care and punishment, life and death.

This piece is drawn from Micha Frazer Carroll’s new book, Mad World: The Politics of Mental Health.

Micha Frazer-Carroll is a writer and journalist who has worked for gal-dem and the Independent.

She is the author of Mad World: The Politics of Mental Health, out now from Pluto.