Cramming 40 People Into a Four-Bed House Wasn’t Enough to Get This ‘Rogue Landlord’ Added to the Government Database

Not one person has been added to the list this year, FOI data shows.

by Hajar Meddah

13 September 2023

What does a landlord have to do to get banned from renting and managing property in the UK? No less than cramming 40 tenants into a four-bedroom house, it seems – and even then it’s unlikely they’ll make it on to the government’s so-called ‘rogue landlord database’.

In August, Jaydipkumar Rameshchandra Valand was handed Brent council’s first-ever landlord banning order for packing dozens of people into a semi-detached house in Wembley, north-west London. The unsafe property was so overcrowded that Valand reportedly had one tenant living in a shack made of pallets in the garden, with a tarpaulin roof and no lights or heating. Yet he’s only been banned from renting for five short years and he hasn’t even been added to the rogue landlord database, Novara Media can reveal.

In 2018 the Tory government created banning orders and set up the database to record bad landlords. Today, both are woefully underused, amid generally dismal returns on an arsenal of enforcement tools that are technically available to local authorities in tackling slum landlords.

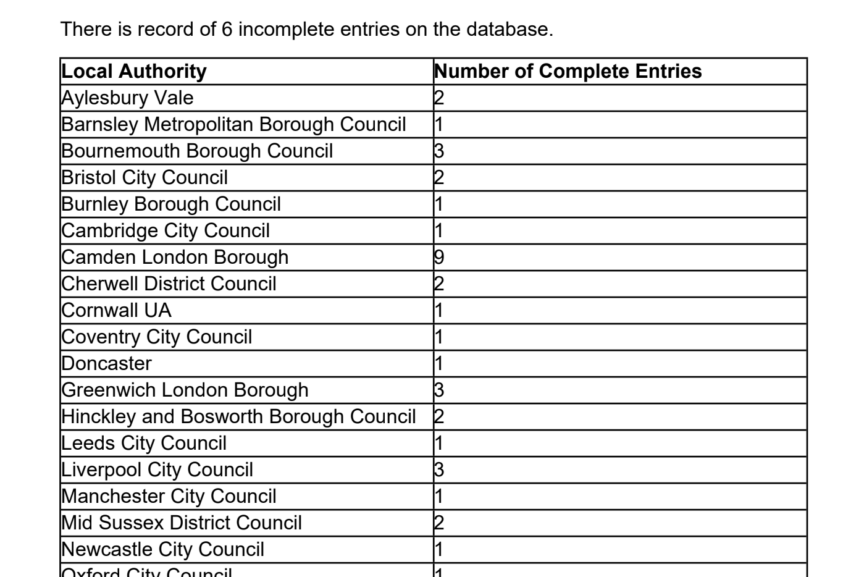

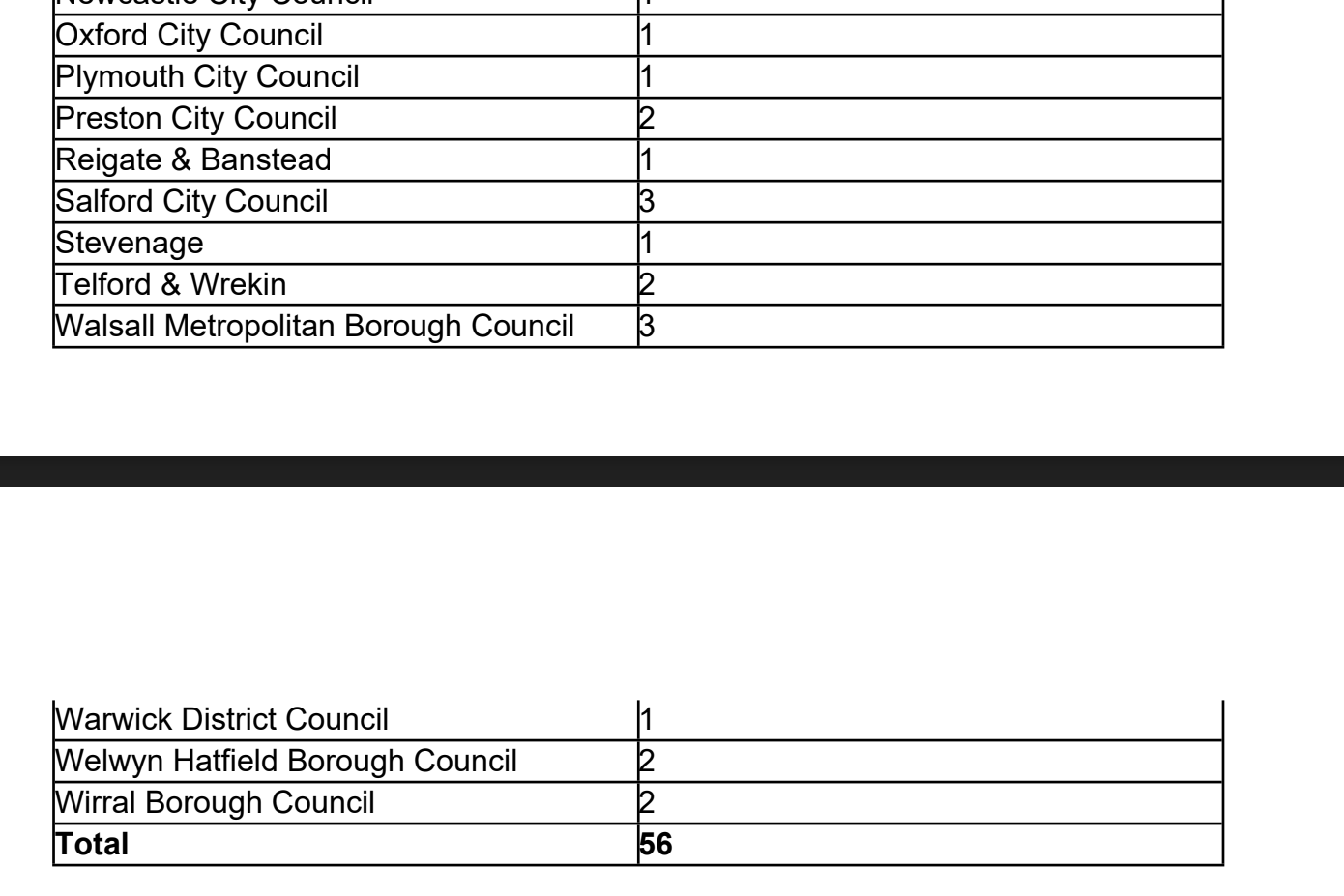

Valand is one of at least six individuals who have received banning orders but not been added to the database, Novara Media can reveal. According to a freedom of information response from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, the number of entries stands at 56; unchanged since the Metro last investigated in 2022.

To qualify for a banning order, a landlord or letting agency must first be convicted of one of more than 40 relevant housing, immigration, or criminal offences. A local authority can then apply for a banning order and if successful, must enter the details into the national rogue landlord database but some councils simply aren’t doing so.

Gavin Barwell, the former housing and planning minister, stated in 2018 that “These measures will give councils the additional powers they need to tackle poor-quality rental homes in their area”. So why, despite government estimates that there are approximately 10,500 rogue landlords operating across England, are there only 16 active banning orders? And why haven’t all of these made it on to the database?

When councils apply for a landlord banning order, they can only do so on the basis of convictions committed after April 2018. As a result, it can take several years for landlords to rack up sufficient convictions before councils can begin the resource-intensive banning order process. And, though the legislation is intended for the “most serious offenders”, nobody can actually agree on what that means.

In a landlord banning order hearing in May, Newcastle City Council hoped to ban Gerard Johnson from letting and managing properties. Johnson had at least 15 convictions and council representatives made clear that he was a repeatedly negligent property manager. The judge was unconvinced of the seriousness of his behaviour and ruled in Johnson’s favour.

The financial future of the landlord also complicated matters. For Johnson, court officials indicated that stripping him of his woefully over-leveraged housing portfolio would be “catastrophic”, despite his compromising of tenant safety by disregarding fire safety requirements.

If successful in their application, councils have a duty to enter the details of a banned individual into the rogue landlord database. The tool was intended to centralise access to information about banned landlords and those convicted of qualifying offences. But housing team employees at three separate councils told Novara Media it takes too long to upload data for every qualifying landlord. Though they’re expected to check new licence applications against the database, usually only a handful of employees have access to it and even then, it’s borderline impossible to verify landlord identities because the entries don’t include unique data such as their date of birth. In

In December 2017, the Greater London Authority launched the publicly accessible rogue landlord and agent checker. Councils were required to upload enforcement records, ensuring data was both recent and much more exhaustive than the national rogue landlord database. As it became clear that the checker was a better tool, the database faded further into obsolescence for many London authorities. However, the checker is not without its flaws as the Evening Standard recently revealed that landlords are finding ways to remove themselves from it.

For Ben Reeve-Lewis, co-founder of Safer Renting, it is also the wider context that makes landlords unaccountable; namely austerity cuts and the Localism Act of 2011 which allowed local authorities to discharge homelessness duties into the private rental sector.

Over the years, as the private rental sector expanded following the launch of buy-to-let and right-to-buy schemes, councils became increasingly beholden to a new bloated class of landlords-cum-mass-housing-providers. Ben knows of one council that spent taxpayer funds intended for enforcement on handing out free city centre parking permits to local landlords.

Communication between council teams is also poor, both because of a tendency towards working in silos and GDPR concerns which impose strict limitations on data-sharing. When coupled with “procedurally unwieldy” legislation and a lack of technical expertise following an austerity-driven brain drain in the sector, it’s no surprise that enforcement rates are so disappointing nationally. Approximately half of local authorities have not prosecuted a single landlord in three years, according to an investigation from OpenDemocracy in 2022.

The lack of magistrate sentencing guidelines for housing-related offences also means prosecutions can yield abysmally poor results. In his day-to-day work, Reeve-Lewis supports tenants facing the threat of illegal eviction. In a recent case, he told Novara Media that the letting agent pulled a gun on a woman and her children during an illegal eviction. Following two and a half years of work to get the agent into court, he received a paltry fine of £400.

Zero-tolerance councils, like Brent, Waltham Forest and Camden, that are willing and prepared to crack down on rogue landlords, are increasingly turning to alternative and much more effective legislation to do so.

Al Mcclenahan, founder of Justice for Tenants, believes that civil penalty notices (CPNs) can help councils turn enforcement around. Speaking to Novara Media over Zoom, Mcclenahan said that there are several local authorities generating millions from licensing and enforcement activities. Among them is Brent Council, which told Novara Media that since 2018, it has administered 270 CPNs and raised approximately £900,000.

Licensing schemes mandate the licensing of all privately rented properties in a designated area, even some not previously licensable. The scheme enables councils to proactively inspect properties, simplifying the enforcement process and, according to an independent review, focuses “resources on areas of concern whilst simultaneously generating revenue to contribute to the costs involved”.

Similarly, all income generated from the CPN, a fine with an upper limit of £30,000, is ring-fenced for meeting the costs of future and current private rental sector enforcement activities.

In 2022, OpenDemocracy found that over 200 councils had never issued a CPN but Justice for Tenants is looking to remedy this. By training some 100 councils in administering CPNs, the organisation expects to improve the effectiveness of the tool, lowering appeal rates so as to maximise funds raised for enforcement.

Despite the organisational focus on CPNs, Mcclenahan doesn’t expect other enforcement tools to fall by the wayside. Instead he believes that they serve an additive purpose, further deterring rogue landlords from pursuing criminal models of operation.

And, nor does he believe that working with non-profits will engineer a path to dependency for councils. He views the outsourcing as a temporary balm while councils recover in the aftermath of the enforcement expertise exodus, allowing them to raise requisite funds and expand capacity to operate independently.

The renters reform bill is also looming on the horizon. It promises a new landlord database that centralises all documentation submitted by landlords, acting as a one-stop-shop for enforcement teams across the country. Reeve-Lewis hopes the database will be in some way publicly accessible like the London rogue landlords database.

For Mcclenahan, Section 58 of the bill has truly transformative potential. It makes landlord legislation a duty for councils, meaning that tenants will no longer have to rely simply on the good political will of councils. By opening them up to strategic litigation, enforcement is set to become a greater priority than before.

Despite these forthcoming developments, the challenges of the private rental sector will not disappear overnight. As Mcclenahan tells Novara Media:

“The evidence so far has been that it is very difficult to drive out the majority of rogue landlords, as once you start enforcing, you realise that you only know about the tip of the iceberg. We are so far from that point that it would be a nice problem to have.”

Hajar Meddah is a reporter at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism.