Taken for a Ride: Inside Uber’s New Race to the Bottom

Welcome to the algorithmic nightmare.

by Polly Smythe

6 March 2025

Natalie had just dropped off a customer at the Ritz Hotel in central London when her phone started aggressively bleeping at her with offers of new fares. “I couldn’t concentrate. I nearly drove over people. You had pedestrians, cyclists, tuktuks all over the place. It was extremely overwhelming.”

Natalie – who chose to give only her first name to Novara Media – has driven for Uber for four years, but this was something new. “It was a really scary experience”, she said. “Uber is putting people’s lives at risk with this.”

This is a relatively new innovation from Uber: Trip Radar. Introduced in 2022, the feature was sold by the tech giant as part of its plan to be “the best platform for flexible work in the world”. Three years later, drivers on a Valentine’s Day strike over low pay, arbitrary deactivations and violent customers added another grievance, chanting at their protest outside London’s City Hall: “Oh Trip Radar, why do you enslave us?”. What went wrong?

As drivers attempt to safely navigate busy roads, accommodate passengers and avoid traffic and diversions, they now have to contend with Trip Radar, which notifies them of offers of new fares to take with a bleeping sound. They have seconds to respond to a cascading list of trips and work out if they’re worth accepting, before quickly bidding against other drivers for them.

Uber states that the feature had been designed to “minimise distractions while out on the road,” and only kicks in when cars are stationary or moving below four miles per hour and never while on a trip – which is the same as the normal experience of getting fares on the app. However, drivers say Trip Radar is inherently more dangerous.

Unlike standard trips, which are directed only to the driver, drivers say that Trip Radar places them in competition with other drivers for trips. That leaves them feeling forced to take their eyes off the road to click on rides as quickly as possible.

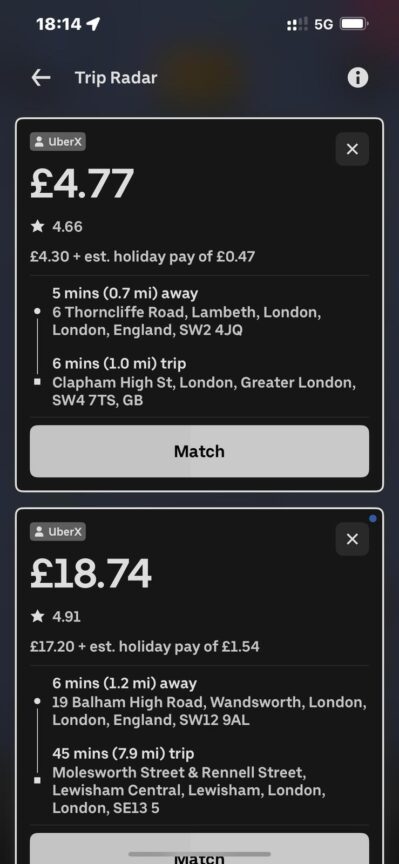

Also unlike standard trips, which present drivers with one trip at a time, Trip Radar bombards drivers with up to five trips at once, who then have to make split second decisions about whether or not to bid, taking in information about distance, length of the trip, and pay.

When Uber launched back in 2011, the platform would directly assign “exclusive” rides to drivers, who could then choose to accept or decline each journey. Trip Radar’s innovation has been to move away from sending drivers individual trips, instead pooling rides and offering them simultaneously to multiple drivers, who can then “bid” in real-time for the same trips.

Uber said that Trip Radar would help drivers to see “more trips to choose from in your area.” But drivers say that the offers listed on Trip Radar are the offers that have already been rejected by other drivers. They argue the feature is just another tool for Uber to systematically lower pay, by forcing drivers to compete to see who will accept the lowest-paid offer.

Chris, who chose not to give his name for fear of reprisal, has been driving for Uber for over a decade. “Trip Radar is designed to pay the driver less,” he said. “It’s about finding whoever is happy to do a job. But if you accept that kind of job, you’re training the algorithm that this level of fare is okay. It’s like Uber is saying ‘How low can you go?’”

Alex Marshall, president of the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB), said: “Trip Radar has turned an already exploitative sector into a dystopian AI nightmare, whereby drivers, struggling to survive, are pitted against each other in a cruel and dehumanising race to the bottom.”

Because of Uber’s secretive algorithm, drivers have no way of knowing why they are assigned or miss out on rides they’ve bid on. In one blog post, Uber claims that the trips go to the “most optimal delivery person.” In another blog post about the feature, Uber said “tapping quickly helps, but it’s not the only thing that determines a match.” Yet in an episode of Behind the Wheel – Uber’s very own podcast – the company’s head of driver operations Neil McGonigle rejects the idea that drivers “compete for offers.”

“It’s not fastest fingers,” McGonigle says. Instead, he states that the algorithm works on proximity, dispatching “the trip to whichever driver happens to be closest with the lowest ETA.”

But drivers have a different explanation. Although Trip Radar offers drivers the exact same trip, it does so for different pay. Uber says that this is only fair – a driver that has to travel further to pick up the passenger may be offered a higher amount.

In 2024, American media non-profit More Perfect Union conducted an experiment to discover whether Uber’s algorithms facilitate wage discrimination. It gathered seven experienced Uber drivers together in a high-traffic area in Los Angeles and asked each of them to open up the app and place their phones on a table next to each other. It found that Uber offered the same rides 46 times to multiple drivers, and that there was discrepancy between fares for 63% of those trips. Uber refuted that this was discrimination, saying in a blog post that differing pay was due to GPS discrepancies. “Fares are calculated using estimated times of arrival based on GPS location, which doesn’t always perfectly match a driver’s physical location,” the blog post said.

Drivers suspect that rides are then assigned to the person willing to accept the lowest paid fare – although Uber denies that this is how it works.

“It seems that the driver willing to accept the lowest fee is given the trip,” said Marshall. “But many fear that the less money they accept, the less they will be offered in future, since the algorithm digests every decision to understand just how hard it can push each driver.”

Last year, Novara Media revealed that Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi told investors on a conference call: “I think what we can do better is targeting different trips to different drivers based on their preferences, or based on behavioural patterns that they are showing us.” Uber continues to deny the claim that it uses data gathered from drivers to determine their pay.

With drivers desperate, it’s easy to push them to accept lower and lower fares. “Let’s say a driver has to pay £500 or £300 a week for the car and insurance before he has even thought about feeding his family, paying his rent, paying his mortgage, clothing his children, or heating his house,” said Natalie. “If Uber gives him a stupid fare, he’s like, ‘You know what? I need to make money.’ You have no choice. I believe that Uber is very aware of the predicament that 99% of the drivers are in.”

Trip Radar’s rollout could be one answer to a problem that’s been plaguing Uber: plummeting driver acceptance rates. When Uber launched, it relied on investor capital to subsidise incentives and bonuses that attracted drivers onto the platform. Then, once it had established a big enough network of drivers, Uber began systematically removing the incentives.

The ride-hailing app admitted as much in a public filing to the American Securities and Exchange Commission in 2019: “As we aim to reduce Driver incentives to improve our financial performance, we expect Driver dissatisfaction will generally increase.”

Cuts to driver pay means that many of the low-paying trips offered on the platform have no value to drivers. By the time drivers have factored in the distance to the passenger’s pickup point the fare isn’t worth the trip. That’s before expenses, like insurance, tax, vehicle fees and maintenance, fuel, licenses, carwash, repairs and phone bills have been factored into working out pay-per mile.

Drivers Novara Media spoke to reported declining pay and plummeting trip acceptance rates. Now, even when driver supply is high, customers might not be able to get a taxi. For Uber, whose market dominance is based on the reliability of its service, this is a problem. Enter Trip Radar, which many drivers see as an experiment in whether the ride-hailing app can prod drivers into accepting rejected jobs without increasing their pay – although Uber refutes this claim.

“The damage done to drivers’ mental health by these constant battles – with the clock, with each other, and with the algorithm – is hard to overstate,” said Marshall.

Poor pay means that drivers have to work for longer. “Physically, it takes its toll on your body,” said Natalie, who’s been an Uber driver for four years. “You get pain in your knees, and mentally it’s draining. It’s draining on the family. I’ve got two little ones, and I constantly have to say to them, ‘No, mommy has to work.’”

An Uber spokesperson denied that Trip Radar is designed to move drivers away from individual trips and said: “Trip Radar provides additional flexibility for drivers and is designed to improve earning opportunities, not decrease them. Trip Radar considers factors like proximity and wait times, before assigning the trip to the best match.

“However, we always listen to drivers, and as a result of some of the feedback received, improvements have been made to ensure Trip Radar provides the best possible earning experience.”

Update, 06/03/2025: This article has been updated to better reflect Uber’s response to some of the allegations made about its practices

Polly Smythe is Novara Media’s labour movement correspondent.