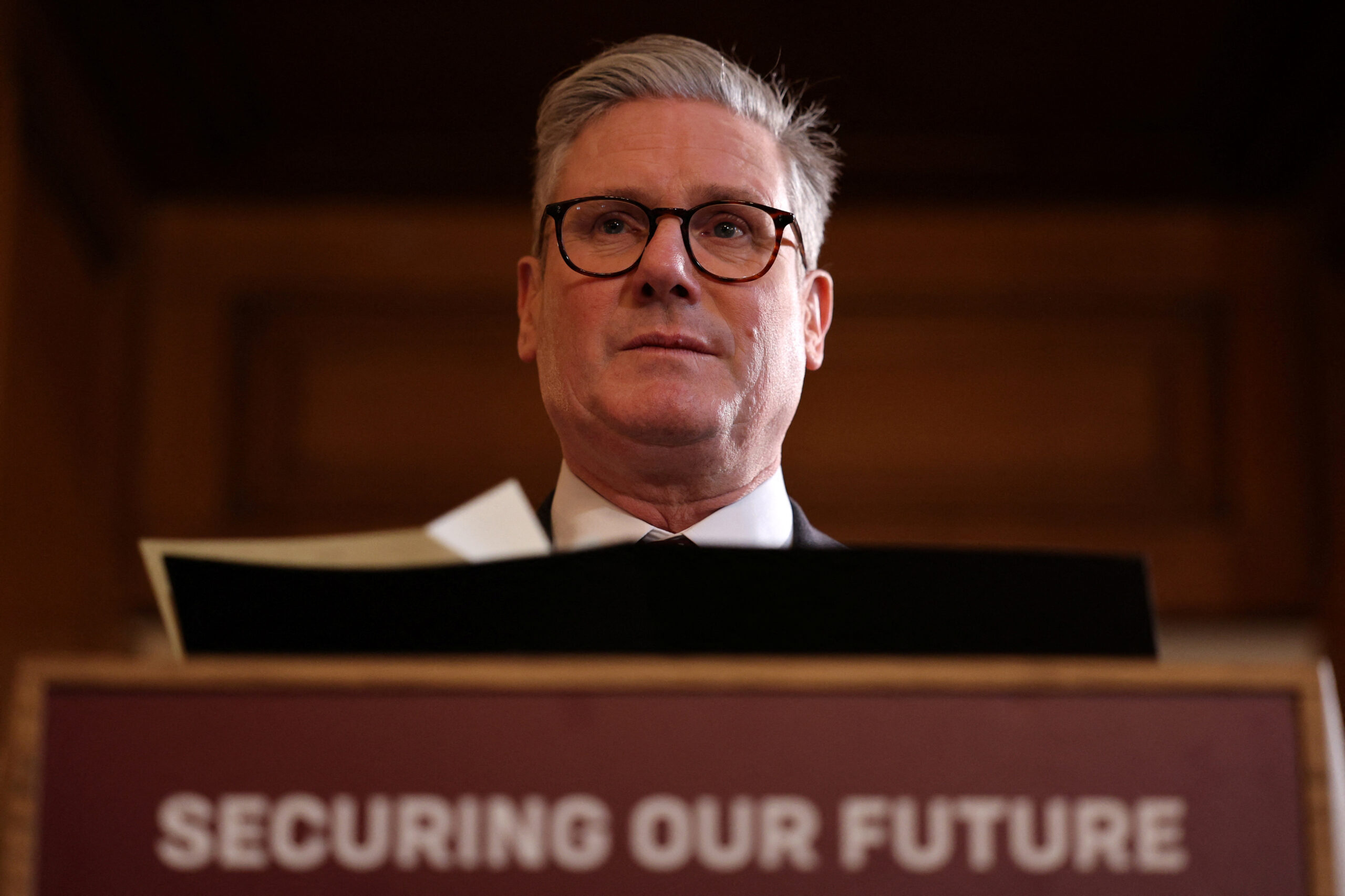

The Real Reason Behind Starmer’s Military Spending Drive

Trump’s lieutenant in Europe.

by Khem Rogaly

13 March 2025

Billionaire-backed? Not us. Unlike mainstream media, Novara Media runs on the support of 12,000 people like you, which keeps us editorially independent. Chip in today and help build people-powered media.

According to Keir Starmer, Europe faces an “existential” moment. Supposedly to preserve the existence of a continent, Britain’s prime minister has embarked on a new agenda, a pale imitation of Washington policy with the same slogan: “peace through strength”.

After more than a decade of pressure from Washington for the UK to increase military spending, Donald Trump has accelerated a redrawing of the US relationship with Europe. Last month, Starmer announced an extra £6bn in annual military spending from 2027, funded through direct cuts to overseas aid. Boxed in by its own fiscal rules, the government has trailed cuts to health and disability benefits. Explaining his plans to slash financial support for disabled people, Starmer told Labour MPs that military spending was central to a government initiative to encourage work rather than welfare.

Far from an attempt to juice the economy through massive defence contracts, this is more akin to George Osborne bombing the welfare state in an F-35. Military spending only supports 0.83% of jobs in the UK – too little to be relevant to most of the population. This agenda is rooted in geopolitical choices rather than economic vision and, despite the rhetoric, it has little to do with national security.

In flight as a foreign policy and fiscal hawk, Starmer is positioning himself as Trump’s lieutenant in Europe. Ramping up military spending is not an attempt to replace the US with an independent European security architecture, but a bid to retain the “special relationship” with Washington by doing as instructed. The new agenda is to maintain Britain’s global military presence and its alliance with the US, and to spend more while doing so.

Starmer’s use of Iraq war imagery by declaring a “coalition of the willing” in Ukraine reveals the nature of the project. Britain’s military is already an expensive and expeditionary global force that operates as a junior partner to the US. Increasing its budget without any attention to this is a recipe for supporting American global dominance.

The best way to understand the composition and purpose of Britain’s military power is through its operation since the turn of the millennium. Between 2001 and 2014, more than a quarter of a million British troops were deployed to support the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, wars in which between 457,000 and 491,000 people were directly killed and hundreds of thousands more died from the devastation of health and economic infrastructure.

Since October 2023, the British military has turned over the colonial territory it controls on Cyprus to a US-led airlift of military cargo used by Israel to commit genocide in Gaza. From the data available on flight logs, Britain has flown more surveillance aircraft over Gaza during the genocide than either Israel or the US.

Cyprus is part of a network of British bases across the world that have nothing to do with national or regional defence. Britain is set to pay Mauritius £9bn to lease Chagos Islands territory for a shared base with the US air force. In the 2010s, new naval bases were opened in Oman and Bahrain to support the deployment of British aircraft carriers in the Asia Pacific.

The government’s latest military strategy called for a global response force that can deploy anywhere in the world via air, land or sea – a further commitment to the capability to intervene “in the place and a time of our choosing”. Meanwhile, Britain will spend £117.8bn over the next decade to keep nuclear weapons continuously at sea in any part of the world even though they rely on the US to be used.

This global strategy has not been touched by Starmer’s announcements. Instead, the government is playing on the fantastical idea that Russia would extend its immensely costly invasion – which has led it to occupy a fifth of Ukraine – across the rest of the European continent.

Even the idea that Britain should ramp up military spending for a new regional security project does not make sense in its own terms. The most likely British contribution to a peace settlement in Ukraine will be further arms exports. During the war, Britain has supplied Ukraine with approximately £3bn of military aid each year while spending more than £30bn annually to equip its own global force. At no point has the debate on rearmament addressed the resources Britain commits to its global posture.

European countries may gesture towards independence, but the rearmament agenda has so far meant much deeper ties with the US military industrial complex. Between 2020 and 2024, European countries doubled their arms imports – nearly two thirds of which came from the US. Over the same period, the UK was Europe’s second highest arms importer, with 86% of its imports American-made. These imports turn over government money to a US military industrial base that pumps cash to shareholders at a much higher rate than commercial business.

In the eyes of Downing Street, we have entered a “Falklands moment” that can turbocharge the Starmer project. Greeted with feverish excitement by the press, the government’s posturing has garnered some support in the polls. More than two in five respondents to a recent Ipsos survey supported increased military spending even if it meant higher borrowing, taxes or less money for public services. The medium-term picture is more complicated: a late January poll suggested that slightly more respondents saw public services as a higher priority than military investment. With a Ukraine peace deal ordered by Washington and harsh cuts on the horizon, the drums of war may be less resonant when met with economic costs.

This is unlikely to matter to Downing Street. The “rearmament” agenda is being pursued regardless of the cuts demanded in return. Green energy development is the latest candidate for the Treasury’s axe. No matter that investment in domestic green industries and public services would leave the country stronger, Starmer’s Labour is determined to prioritise Britain’s global military presence at any cost.

Khem Rogaly is a senior research fellow at Common Wealth think tank.