‘I Feel Like an Uber Slave’: The Illnesses Affecting Private Hire Drivers

‘Mini cabbing, mini killing, and eventually mini dying.’

by Polly Smythe

18 June 2025

Paywalls? Never. We think quality reporting should be free for everyone – and our supporters make that possible. Chip in today and help build people-powered media that everyone can access.

Jonathan Omolewa, 68, began working in London as a private-hire driver in 2005. The 20 years he’s spent behind the wheel of a car, dropping passengers to their airports, nightclubs and hospitals, has been hard on his body: he’s been diagnosed with chronic pain, back problems, diabetes and joint issues. “When you do this kind of work, pain is normal,” he said. “Mini cabbing, mini killing, and eventually mini dying.”

Omolewa isn’t alone. Alex Marshall, president of the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) trade union, said health issues are “pervasive” across the private-hire industry.

“Ask any driver privately and they’ll tell you about how common poor health is in the industry, whether that’s physical injuries from spending hours sitting down, or mental health issues caused by the isolation and exhaustion of working extreme hours for such low pay,” he said.

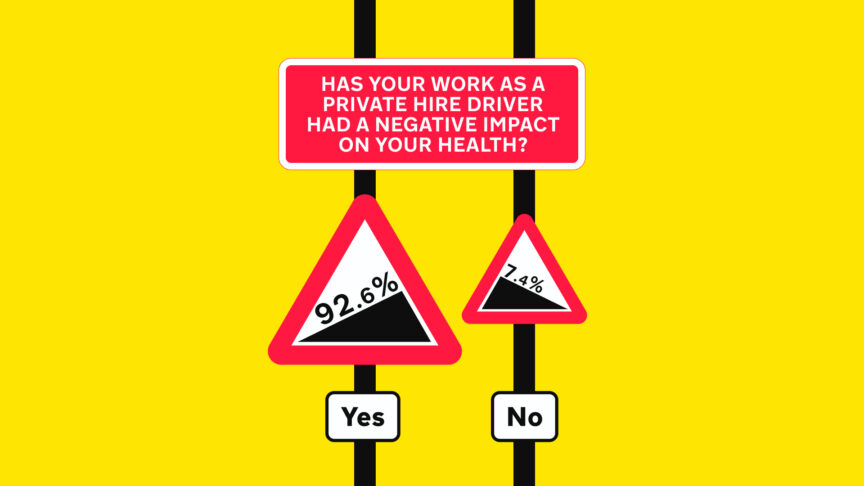

A survey done by the IWGB of 120 private-hire drivers, shared exclusively with Novara Media, found that more than 90% of drivers who responded felt that work had a negative impact on their health.

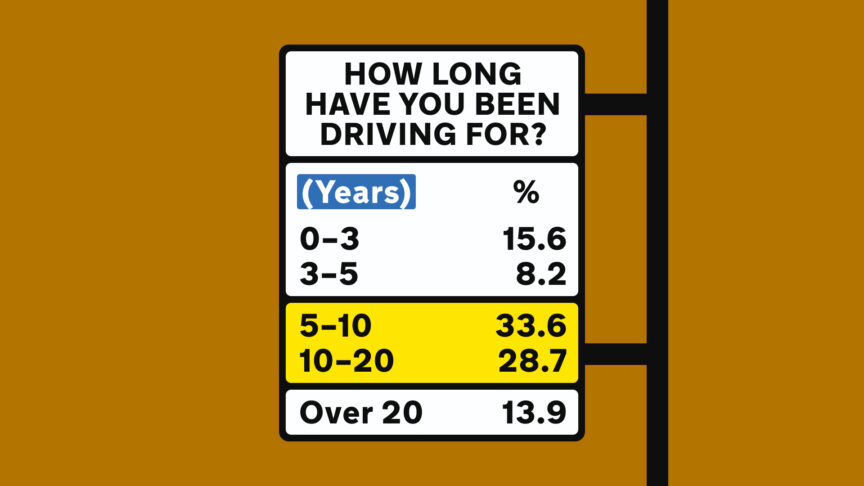

Marshall said the survey offered a rare glimpse into the under-reported crisis of poor health among drivers, who can spend up to 100 hours a week in their cars, desperately trying to earn enough to make a living.

While there has been reporting into the poor health of workers who drive for a living, including taxi-cab drivers and lorry drivers, little attention has been paid to how these health conditions could be turbocharged by the specific dynamics of the gig economy.

Gathering data on the health of private-hire drivers is difficult, as drivers feel a stigma attached to poor health. They are under constant pressure from licensing authorities to prove their fitness in order to continue working.

Dr Joe Kearsey, an academic with a focus on private-hire drivers, said the data “helps to build a clearer picture of an often-under-reported aspect of platform-based private-hire drivers’ work.”

Since Uber’s UK launch in 2012, the number of drivers working for ride-hailing platforms, including Bolt and Addison Lee, has swelled. But hidden behind the language of “innovation” and “disruption” deployed by the companies to describe their business models is a largely migrant workforce who have endured often dire working conditions.

A rare health-related blog post addressed to drivers about their health from Uber in 2016 details tips on making “conscious healthy choices” – exercising for 15 minutes a day, taking short walks, and tracking your fitness. Drivers should remember to eat breakfast: preserving your health “can be as simple as an egg”.

However, the survey reveals that for some drivers, the reality of private-hire driving is aching bodies, passenger violence, destroyed family lives, suicidal thoughts, loneliness and medication.

The toll: ‘It’s the worst job ever.’

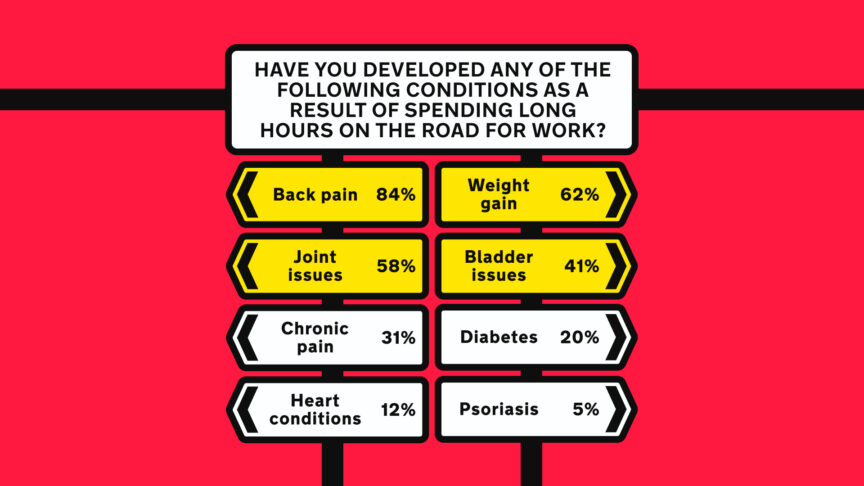

The most common problem reported by drivers was back pain, with nearly four in five respondents describing symptoms. Sitting down for up to 17-hours at a time, for seven days a week, places an immense pressure on the lower back, and puts drivers at risk of a herniated disk, pinched nerves and muscle strain.

Prolonged sitting in one spot for hours can also cause joint pain, reported as an issue by three out of five drivers. As hours spent at the wheel outpace time spent clocked off, it’s harder for drivers to find the time to exercise, or to cook at home, with 62% returning weight gain as a problem of work.

It’s not easy for drivers to take a bathroom break, and just under half of the drivers surveyed reported bladder issues (41%). Public toilets are few and far between, and drivers find themselves unwelcome in cafes and restaurants if they don’t buy food or drinks first.

If a public toilet can be found that’s open and clean, there’s no guarantee it will come with a parking spot, and stopping the car without one means running the risk of blocking traffic, losing out on a good trip, or getting a hefty ticket. If facilities can’t be found, drivers are forced to resort to plastic bottles. Left unable to urinate when necessary, drivers report bladder infections, kidney stones, and prostate issues.

Kearsey said: “Without a dedicated physical workplace, spaces where platform-based private-hire drivers can stop and take a break are often few and far between, especially in busy cities like London.”

“Given that platform companies and private-hire licensing authorities are facilitating a model which relies on the constant availability of thousands of drivers, it is incumbent upon them to provide the rest places and facilities which all workers are entitled to.”

Other health conditions reported were psoriasis, heart conditions, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, tennis elbow, high cholesterol and blood pressure, sleep problems, eye issues, fatty liver, restless leg syndrome, and cellulitis, an infection of the skin and soft tissue.

While many of the ailments reported by drivers are those associated with traditional cabbing – termed “taxi cab syndrome” in a 2014 paper – they are being uniquely turbocharged by the algorithm pressures of gig economy work.

In the UK, private-hire drivers are classified as workers and not employees. That means that platforms can’t enlist drivers to work at particular times and locations, or dictate set schedules. To ensure that the supply of cars is always high enough to match rider demand, companies have developed sophisticated algorithms that keep drivers on the road for as long as possible.

But while these algorithms rely on data generated by drivers’ interactions with the app’ s interfaces and with passengers, details of how they exactly function remains a mystery to the workers.

This secrecy means that drivers are left to speculate on the fundamental dynamics that govern their work. Of particular concern to drivers is what their acceptance and cancellations rates – the number of trip requests accepted divided by the number of ride requests received, and the number of trips accepted and then cancelled – means for them.

Drivers say they fear that rejecting trips will result in them being offered fewer or worse trips in the future, or even in their accounts being deactivated, which pushes them to stay online for longer.

One tool deployed by the apps to nudge drivers into accepting trips is “forward dispatch”, which asks drivers if they would like to accept a new trip before they’ve completed their current one.

This automatic queuing of trips has been compared to Netflix’s loading up of another episode while the current one finishes, leaving drivers and viewers in a position where it takes “more effort to stop than to keep going.”

Just as people binge-watch Netflix, so too does the scheduling feature make it harder for drivers to go offline, and pushes them to drive for longer, without breaks. While forward dispatch can be paused if the driver logs off, it will automatically start back up again once they log back in.

Kearsey said the data highlighted how the “toxic combination of deteriorating pay and punitive algorithmic management has impacted the health of platform-based private-hire drivers.”

“These drivers increasingly have to work longer hours to make enough money to get by,” said Kearsey. “All while platform management forces them to maintain low cancellation and high trip acceptance rates while at work.”

Independent contractor or employee: ‘None of these operators care about your health.’

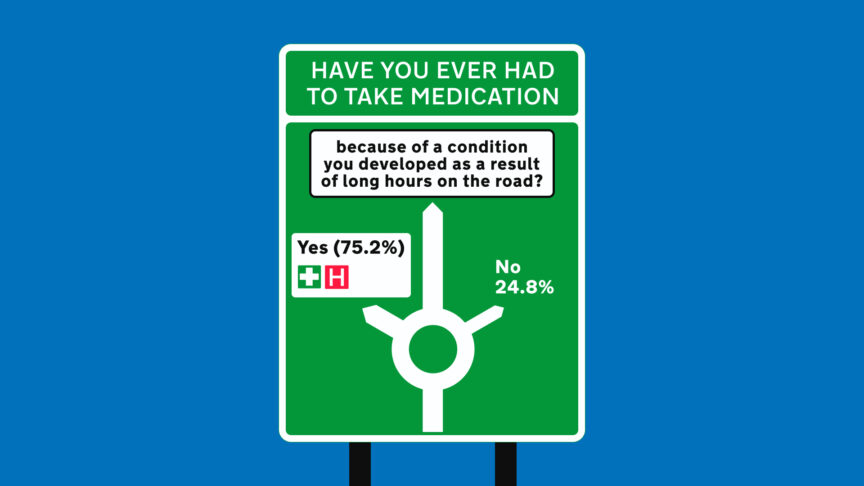

Classed as “workers” – as opposed to employees or contractors – private-hire divers are not legally entitled to sick pay.

This leaves drivers to manage their conditions themselves, and almost 90% said that they had felt pressure to return to work before being fully recovered from illness or health problems. Over 90% said that they felt pressure to keep working whilst unwell.

While Uber does offer a form of sick pay, drivers say that it’s extremely difficult to claim and that it tends to be inadequate.

Despite the severity and scope of health problems experienced by drivers, it’s difficult for them to talk about their health openly. In order to legally work, private-hire drivers have to be licensed. For those working outside of the capital, licenses are granted by the local council, with Transport for London granting them for those in it.

Generally, they require drivers to be assessed by a medical practitioner with full access to the applicant’s medical records, and pass a medical exam. That requirement – to be medically fit in order to be licensed – can prevent drivers from seeking help when they are sick or distressed.

And they get little help from their employers: drivers say that efforts by private-hire companies to address the occupational hazards that plague them are uneven at best, and practically non-existent at worst.

Drawing people to driving by the initially high wages and welcome bonuses, the app-based platforms worked hard to attract a critical number of vehicles in order to maximise their growth. Once a network of drivers was firmly established, facing investor demands for profitability, platforms began eliminating the incentives and cutting the pay that had attracted drivers to them in the first place.

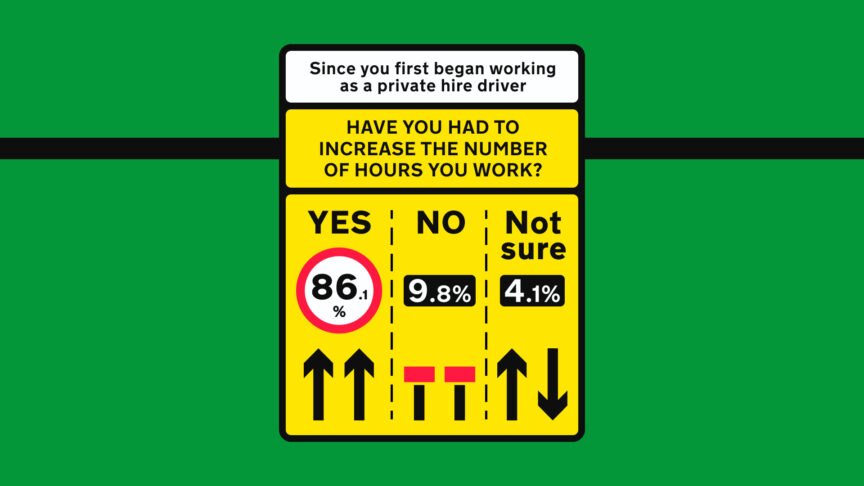

As private-hire drivers’ pay has fallen, the costs of working – insurance, petrol, carwash, vehicle fees and maintenance, licenses, carwash, repairs and phone bills – have shot up. Where it once took drivers seven or eight-hour shifts to make enough money, hours like those are now a thing of the past, and doing enough jobs to earn the same amount as a few years ago can now mean working for up to 16-hours a day.

“After working 12 hours, when I see my earnings, I get more mental stress,” said one driver.

Nearly 30% of drivers surveyed said that they worked over 60 hours each week. With lower fares meaning longer hours, drivers reported that the health problems detailed in the survey were more acute as a result of the ever-extending shifts they had to work in order to cover bills and rent.

“Renting a car and covering fuel expenses alone cost me over £500,” said another driver. “To make that money back, I’m forced to work long, exhausting hours – just to cover basic living expenses.

“On top of that, Uber and Bolt continue to take a significant portion of earnings through high commission rates. It feels like drivers are being exploited rather than supported. This isn’t sustainable work – it’s modern-day slavery.”

Mental health: ‘The future certainly is not bright.’

Drivers said that one result of the solitary nature of the work, long hours and stress brought on by economic desperation was often depression.

This was exacerbated by night-work, frequently preferred by drivers, as there’s less traffic and a guarantee of work due to the night-time economy. But night-work also means sleeping during the day, keeping drivers from their children and partners. Multiple drivers reported work impacting on their relationships, with one reporting that work was “destroying my family life” and another that he’d been left with “not enough time to spend with family.”

One driver reported that they didn’t have “enough time for sleep due to working 12-17 hours doing shitty jobs,” while another said that they were “not resting enough due to low pay and trying to keep up.”

Another said that working unsociable hours had resulted in “a very lonely life.”

Many drivers reported feeling trapped and hopeless. Having borrowed money to pay for or lease newer and better cars to secure better ratings from customers, or to benefit from electric vehicle incentives, drivers now find themselves deeply in debt.

“It’s the worst job ever,” said one driver. “But once you are in you can not get out because you have car costs.” “It feels like I’m chasing my tail on a daily basis,” said another. “I literally don’t see no light at the end of the tunnel and constantly in a life loop where I’m not getting nowhere. I have been to my GP to speak to him about it, he confirmed that I was clinically depressed.”

One driver reported that his mental health had “suffered immensely,” having in turn a “knock on effect with everything else in life […] The outcome is not good and the future certainly is not bright.”

Attacks: ‘Always in danger.’

In 2021, Bolt driver Gabriel Bringye was stabbed to death by a group of teenagers. Despite his vehicle sitting stationary for six hours while booked on a job, Bolt had no system to detect and raise an alarm. That same year, Uber driver Ali Asgha was murdered by his passengers after he dropped them at Coco’s Grillhouse and Desserts instead of Koko Lounge in Rochdale. Two years later, an Uber driver was stabbed twice in the chest in Balham.

The threat posed by passengers contributes to the anxiety and depression of drivers. One driver said: “Taxi driver life is always in danger[ous] conditions, too many bad stories have happened to taxi driver[s].” Another said that they had to deal with a constant “fear of being discriminated against dealing with racial abuse. Very stressful and depressing job not worth the money.”

“I’m sure they will come up with something when someone falls off the cliff from this Uber exploitation,” said one driver. “I feel like an Uber slave. I have had it with Uber, but it feels like an abusive husband you can’t get rid off and keep going back [to].”

A Bolt spokesperson said: “Drivers who earn through Bolt have complete freedom to choose when, where and how they work, and their wellbeing remains our priority. Drivers operate as self-employed entrepreneurs, choosing which trips they accept, and we never penalise drivers based on acceptance or cancellation rates.”

Uber and Addison Lee did not respond to requests for comment.

Polly Smythe is Novara Media’s labour movement correspondent.