Filth: Space Junk Is Always Somebody Else’s Problem – But Eventually Someone Is Going to Have to Clean It Up

by Eleanor Penny

8 May 2020

Five hundred miles above Siberia, a dead Russian satellite crashed at breakneck speed into a US-based communications satellite.

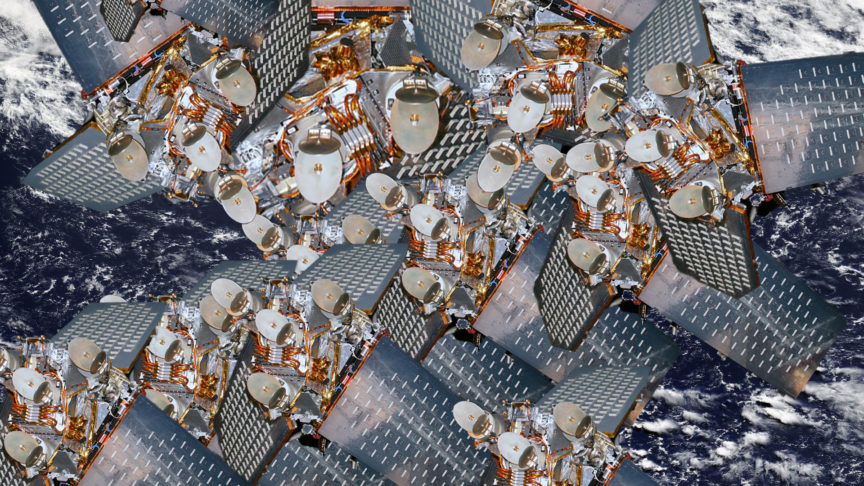

Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33 collided at over 22,000 miles per hour, instantly shattering into thousands of pieces. Now, over a decade since the crash, shards of Cosmos and Iridium are still whirling around the stratosphere. They are not alone. Earth’s orbit is cluttered with space junk, the flotsam and jetsam of a decades-long arms-race for extra-terrestrial territory, and a new commercial scramble for supremacy in the satellite-dependent markets (like telecommunications) which regulate our earthly economy from the skies.

Zombie satellites drift through the heavens, along with scattered shrapnel from countless re-fittings, collision detritus, nuts and bolts, casings and paint flakes; an estimated 130 million pieces – not counting the micro-debris which can elude the tracking mechanisms of those trying to get a handle on extra-terrestrial trash.

Some of the debris looses altitude and harmlessly burns up when it re-enters the atmosphere. But at such high speeds, even the tiniest scraps of metal or flecks of paint can pose a major engineering problem. According to Nasa, a “1-centimetre paint fleck is capable of inflicting the same damage as a 550-pound object travelling 60 miles per hour on earth. A 10-centimetre projectile would be comparable to 7 kilograms of TNT”.

And collisions create more shrapnel, which creates more, which creates more, in a chain reaction that Nasa scientist Donald Kessler predicted could one day render the earth’s orbit unusable, inhospitable for the tens of thousands of satellites being readied for launch, untraversable for off-world probes. Theorised in 1978, the Kessler Syndrome once sounded outlandish – but looks increasingly like a serious prognosis, as the new Silicon Valley space race gathers furious pace, and the problem of how to sift garbage out of the stratosphere remains unsolved.

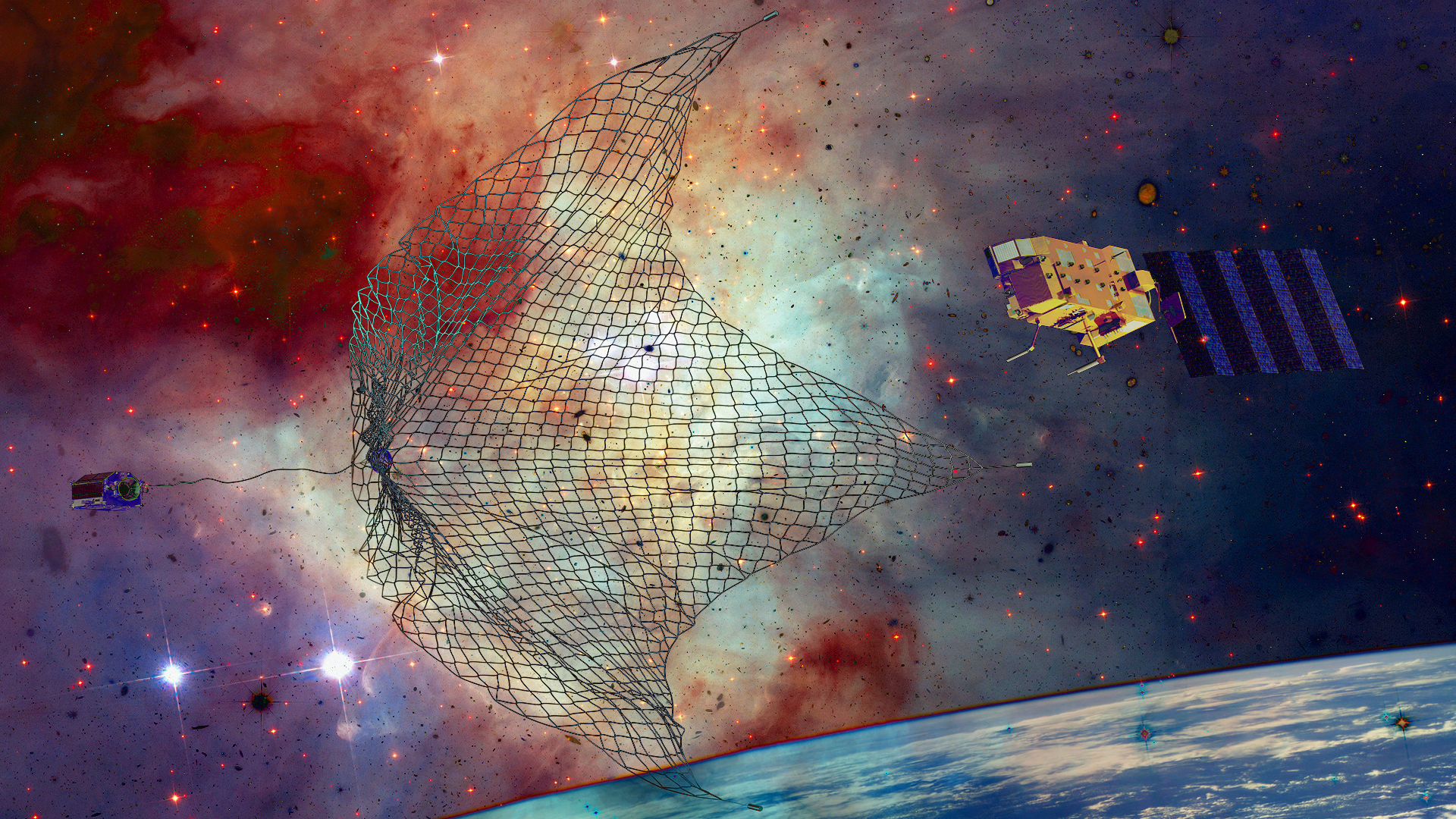

Some solutions have been tested – ranging from lasers to space harpoons, from drag nets to giant magnets to garbage disposal robots charged with swiffering up the smaller particles. Every single one dangerous, difficult and wildly expensive. More recently, satellites have been fitted with end-of-life engines to propel them into the atmosphere where they can burn up – or into the ‘graveyard zone’, out of the main traffic lanes, where retired satellites can go to while away the earth’s lifespan in peaceful contemplation of a job well done – without wandering into the path of a major communications hub and unwittingly tanking a major piece of the human planet’s infrastructure.

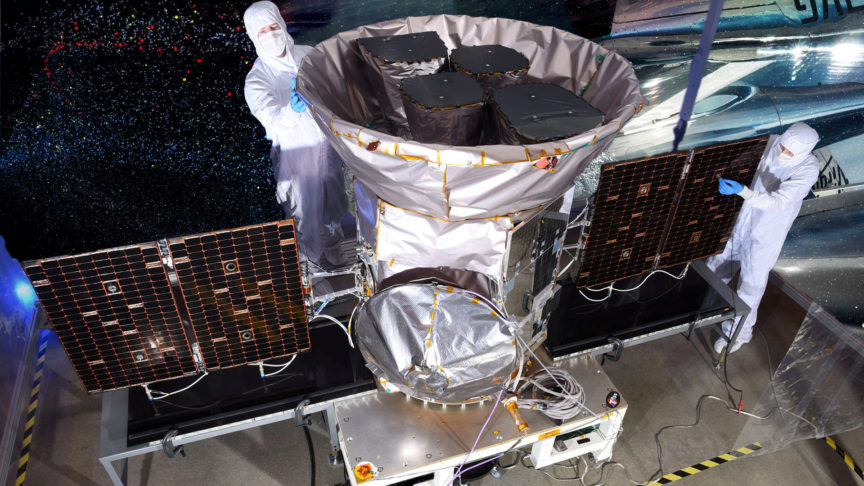

Some determined efforts are being made to start tackling the problem in earnest. Research into possible solutions is heating up.

Califorian space-mapping company Leolabs has started tracking smaller debris.

Last year, the European Space Agency contracted a private Swiss company to develop the world’s first mission to shift the debris, with what essentially amounts to a kamikaze robot designed to grab on to space junk before plunging towards the earth.

But there is no universal requirement for nations or private companies to build in anti-junk strategies. And space debris has a nasty tendency to stray out of the immediate zones of the satellites which birthed it, mixing indistinguishably with other pieces of flotsam until it reaches a critical state economists like to call ‘somebody else’s problem’.

At the best of times, it’s hard to get governments and companies on the hook for clearing up their terrestrial messes. It’s that much harder when the problem of space junk is so tricky, so costly, and so, well, everywhere. A determinedly social problem is very hard to solve via the airless, grinning mechanics of profit-making, and through private companies with a tendency to offshore responsibility for their own filth. Particularly when there aren’t international bodies capable of drawing up or enforcing universal standards on space clear-up.

And as the tectonic plates of global geopolitics shift, the cold war power ententes which underwrote the reluctant interstellar cooperation of the last century become so much space junk.

We are at the beginning of a new scramble for space. Billions of dollars are being ploughed into private space going enterprises, as a shining generation of moonshot venture capitalists train their sites on the boundless commercial possibilities waiting beyond the grip of the Earth’s surface.

The trillion-dollar fortune of rare metals lurking in near-earth asteroids, the promises of engineering in low-gravity, the delicious commercial ventures of dominating internet provision, GPS services, surveillance, weather systems monitoring; where the scions of earthly fortunes vie for a throne among the stars. Market capture is the name of the game, as companies and nations vie for control of off-world resources and mining rights, for the ability to charge rent on satellite infrastructure and tolls on the silk roads of space.

They have to shell out a lot for a place at the gambling table, but with one eye on a digital economy increasingly reliant on tech infrastructure and rare earth metals – they can win big.

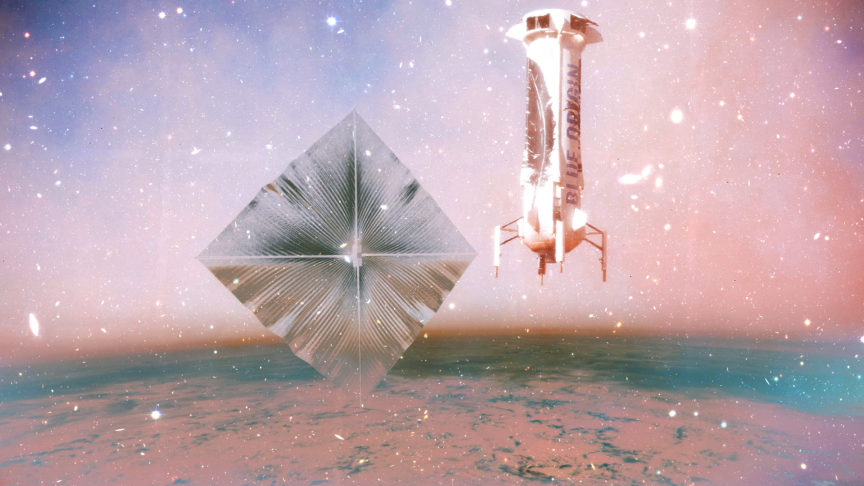

Blue Origin has talked about off-world living and heavy engineering on the moon, SpaceX has plans to launch tens of thousands of micro-satellites to provide unitary worldwide internet coverage, and (creatively) destroy the competition. Some predictions warn that these micro-satellites might block out astronomical equipment peering into the universe. Yet more warn that the ramping number of satellites sharpens the question of the trash they tend to create.

Cold War era treaties once prohibited profiteering in space, declaring it a neutral zone belonging to no earthly nation. Though it sounds delightfully utopian, it was mostly about trying to prevent nuclear powers stationing rockets in space. But with the fall of the USSR – and the moonshot potential of astral profiteering – the power balance underwriting the treaties shifted. Since then, signatories have been quietly dismantling its power.

Trump has made good on Obama-era legislation declaring the right of private companies to profit in space. China, Russia and the USA are all developing specific military forces for space, in anticipation that they might once again have to duke it out for privileged access to the most profitable sites. The head of China’s space programme has compared the moon to the Diaoyu Islands; a collection of sparse rocks in South China Sea – with key strategic, military and economic importance.

This is state-building in space; expanding the military, legal and practical capacities of the nation to enshrine the mechanisms of profit-making. This is capturing the terra nullus of the atmosphere and bending it to the logic of the warring nations of the planet below.

But the question of space-junk remains unanswered, requiring the kind of multilateral cooperation and commitment to regulation of commerce hard to achieve between nations gearing up to win big in the new wild west.

You might think that a threat to the long-term viability of these billion-dollar ventures, not to mention a threat to some of the basic infrastructure of the global economy, might concern everyone. But when it comes to commerce, ‘everyone’ is not an obvious or natural category. Shareholder dividends are uninterested in the fate of ‘everyone’.

This is where organisations of accountability ideally come in to make sure that companies clear up the mess for which they’re responsible. This is where governments and civil society organisations repeatedly refuse to protect a natural commons which cannot survive the machinations of organisations blood-bound to protect the private and profit, whatever the cost.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the third instalment in a new series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.

Part one is here: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground

Part two is here: Racist Scaremongering Around Covid-19 Is Nothing New. We Have Always Blamed Racial Others for Disease