Lula’s Back, and Bolsonaro is Feeling the Heat

The former president’s return is one of many things making his rival sweat.

by Benjamin Fogel

26 April 2021

After spending 580 days in prison for corruption convictions which were annulled in March, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, better known as Lula, is free. Lula’s return to the political scene comes as Brazil increasingly finds itself a pariah state, thanks both to its state-sabotaged Covid-19 response – the country’s health system is collapsing under the weight of 380,000 coronavirus deaths, which together helped to bring down average life expectancy by 1.94 years in 2020 – and its appalling environmental record. It is perhaps unsurprising that almost immediately upon his release from prison, Lula became the favourite to win next year’s presidential elections.

Lula, Brazil’s first working-class president, left office in 2010 with an unthinkable 83% approval rating. Over the years, he has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to reach across political divides and find ways of governing in adverse conditions. His years in government saw rapid economic growth, millions lifted out of poverty, a historic expansion of higher education, basic services delivered to the poorest regions of the country and what seemed like the emergence of Brazil as a global player.

Lula’s political return to the political scene was made possible by two Supreme Court victories against the largest anti-corruption investigation in Brazil’s history, Operation Lava Jato (Car Wash). First, on 8 March, the court ruled that the federal court in the southern city of Curitiba that originally convicted him of passive acts of corruption and money laundering did not have jurisdiction to do so. Then two weeks later on 24 March came another ruling: that the judge in the original trial, Bolsonaro’s former Justice Minister Sergio Moro, had been biased against Lula, colluding with prosecutors to secure a conviction.

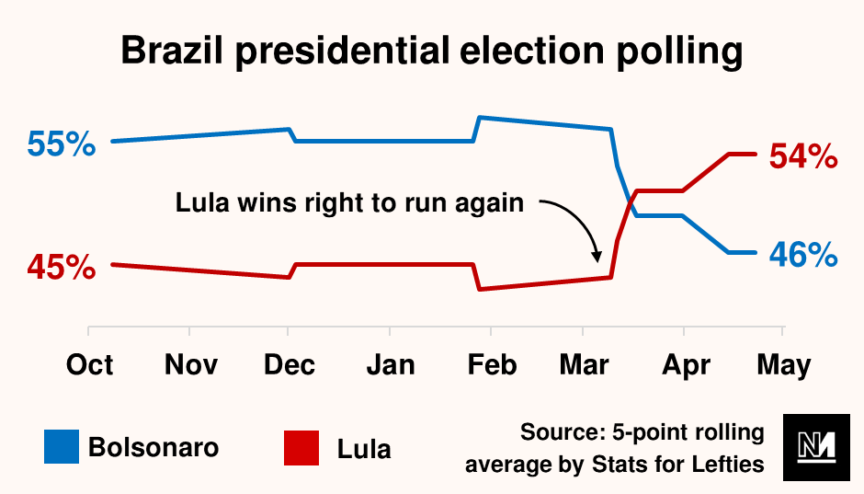

With Lula now eligible to run in 2022, the chessboard of Brazilian politics has been reset. The latest polling shows Lula leading by a significant margin – 52 to 34% – in a hypothetical second-round run-off. The reasons for this are twofold. First, Lula remains popular with much of the Brazilian electorate, particularly working class voters and those residing in the poorest regions of the country. Second, the effects of economic crisis, combined with an uncontained Covid-19 outbreak, are leading more and more Brazilians to blame Bolsonaro and his government for the devastating effects of the pandemic.

Lula’s strategy is to occupy the centre ground, rallying the left alongside everyone opposed to Bolsonaro, including centrists, conservatives and even sections of capital. While such a broad front is necessary, it is hard to imagine his election campaign will unfold without incident. Lula still faces the consequences of years of defamation campaigns, criminal convictions and irrational hatred from sections of the elite and upper-middle classes. Changes within the Brazilian political climate haven’t stopped elements of the domestic and foreign press from continuing to label him and the Workers’ Party (PT) he represents the “extreme-left” version of Bolsonaro, or invoking the dreaded spectre of populism (the irony being that Lula has already served two terms as president and governed from the centre-left, making him hardly some unknown entity or dangerous radical). Nor will he be getting any favours from the centre-right, who not only helped topple Dilma Rousseff’s democratically elected government in 2016 but used the opportunity to pass a series of historic attacks on social rights, and largely supported Bolsonaro in 2018 as the “lesser evil”.

Bloomberg really need to stop pushing this nonsense of Brazil being caught between two extremes and the “far-left” Workers Party as if they hadn’t already covered 4 terms of PT governmentshttps://t.co/OBSEwHGNal

— Benjamin Fogel (@BenjaminFogel) April 21, 2021

Still, with every coronavirus death and food price hike, anti-Lula sentiment will fade, and memories of the relative prosperity and stability of his term in government could grow stronger in the minds of voters.

Then there are the other challenges facing the incumbent. Besides struggling to adjust to the new realities of the Joe Biden administration after tying his political fortunes so closely to Trump’s, Bolsonaro also faces a Senate investigation into his handling of the pandemic, beginning on 27 April and led by one of his most ruthless critics, Senator Renan Calheiros. The investigation is clearly making the president sweat. “Bolsonaro is scared to death of the CPI (Congressional Investigation),” Humberto Costa, a former Health Minister and PT senator told Al Jazeera, “of the denouncements that will come and what will be revealed … of the possibility of impeachment and not getting re-elected next year.” Meanwhile, 60 impeachment requests sit on the desk of the speaker of Brazil’s lower house.

Bolsonaro’s allies still control both the Senate and Congress, after he bought support from Brazil’s numerous rent-seeking parties. However, if these opportunists see their fortunes better secured by breaking with the government, they will not hesitate to jump ship. There are already signs of this happening: since Lula’s corruption charges were annulled on 6 March, cabinet ministers and the heads of all three branches of Brazil’s armed forces have quit.

Taking together Brazil’s long history of military coups and revolts, Bolsonaro’s frequent threats to use the armed forces against the Supreme Court and Congress, and the increasing radicalisation of the rank and file, there is a very real threat of insurrection from Brazil’s security forces. A number of such moves have been attempted recently by members of the military police in defiance of lockdown measures. Meanwhile, just this weekend, Bolsonaro threatened to deploy the military in order to restore order if the lockdown measures implemented by state governors, and which he opposes, cause “chaos”.

Given the vaccine-resistant variants created by uncontrolled Covid-19, the stakes in next year’s Brazilian elections couldn’t be higher. The fact that Lula is now the favourite testifies not to only his abilities as a politician (Perry Anderson once called him the most successful politician of our time) but also the failure of the opposition both on the left and right to present a credible alternative to Bolsonaro.

if lula wins the presidency, it will be because of thishttps://t.co/j4mkAHTrVD

— ☀️👀 (@zei_squirrel) April 23, 2021

Yet for all the hope that Lula may have generated on the Brazilian and international left, it’s important to bear in mind that Bolsonaro is down, but not out. His base of around 30% of the electorate is holding, and he still has the support of much of the country’s businessmen and security forces. A year is a long time in the viper’s nest of Brazilian politics. For now, however, Bolsonaro and the far right are on the defensive, leaving a space for the left to advance an alternative politics that could transform Brazil and perhaps the entire region for the better.

Benjamin Fogel is a PhD candidate in Latin American History at New York University and a contributing editor for Jacobin.