Labour Is Bracing Itself for a Rough Ride Next Week. What’s Actually Going to Happen?

The opposition usually wins big in local elections. Starmer probably won’t.

by Ell Folan

27 April 2021

Next Thursday, Britain will vote in its first electoral contests since 2019. The 6 May local elections will be a key test for Starmer’s Labour – in order to have a shot of winning the next general election, the party must perform well.

Yet sources within Labour have already begun briefing the media that they expect a disappointing result. Starmer himself recently referred to the upcoming local election as “tough”. One shadow cabinet member was even more explicit to the Financial Times: “Our expectations are that we’re going to really struggle.”

Indeed, some polls currently have Labour trailing the Conservatives by double digits. However, others show a closer race, with the Tories just 3 points ahead with Ipsos MORI and 6 points ahead with Survation – both of which would suggest clear swings to Labour. But what would a good result for Labour look like? And what can we actually expect?

What’s up for election?

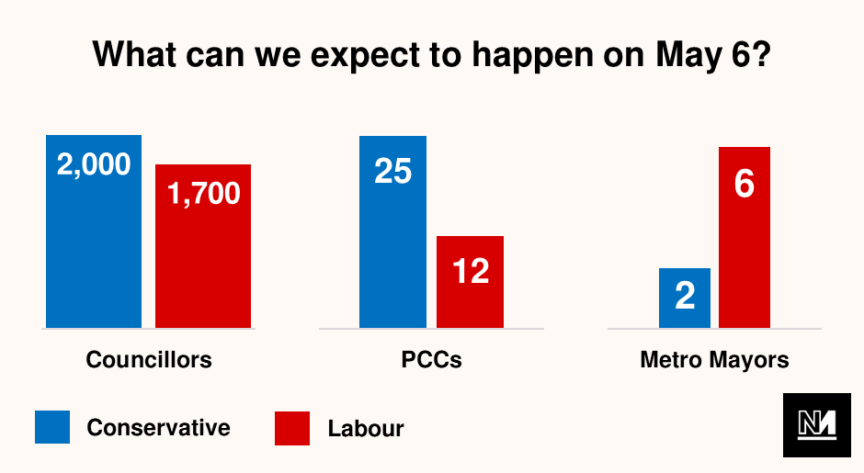

In May, every eligible voter in Great Britain will get the chance to vote. Those in Scotland and Wales will elect devolved parliaments. In England, nearly 5,000 seats in a total of 150 councils will be contested. English and Welsh voters will also elect regional leaders, including 40 Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs), eight Metro Mayors, five local mayors and the London Assembly.

What was the result last time?

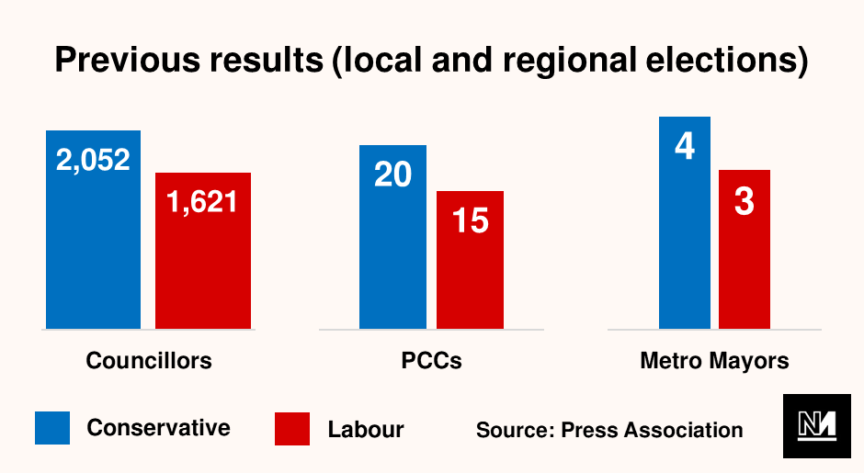

Due to the 2020 elections being deferred a year by the pandemic, some of the areas up for election next week were last contested in 2016, others in 2017. The below graph shows the previous result for the two major parties in local and regional elections in England and Wales:

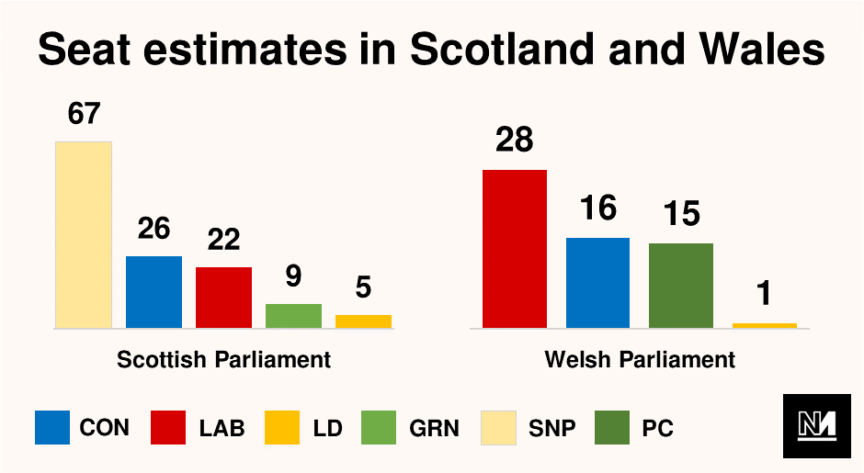

In Scotland and Wales, the previous election saw minority governments returned in both nations. The SNP lost their overall majority but continued in power with the support of the Scottish Greens, whilst in Wales, Labour won 29 out of 60 seats and formed a minority government with the Welsh Lib Dems.

What would a good result for Labour look like?

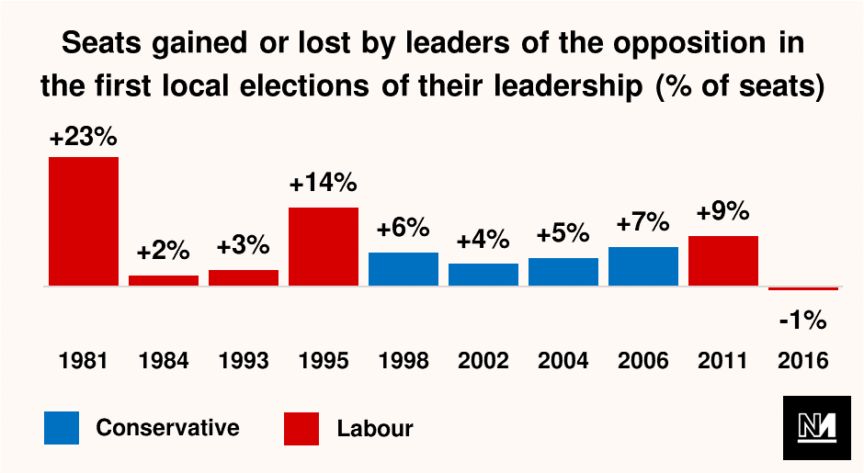

History suggests that, in order to have a shot of winning the next general election, the opposition needs to perform well in local elections. Of the last 10 opposition leaders, nine gained seats in their first set of local elections. Indeed, the two who became PM (Blair and Cameron) gained over 7% of the seats up for election.

The graph below illustrates these figures. As the number of seats up for election varies year to year, I have shown the changes as a percentage of total seats.

From this, we can say that a good result for Labour would be to make gains representing over 5% of the seats for election (240 gains). This would not be an exceptional performance, but a better one than Neil Kinnock managed in 1984 (+2%), John Smith in 1993 (+3%), Ian Duncan Smith in 2002 (+4%) and Jeremy Corbyn in 2016 (-1%).

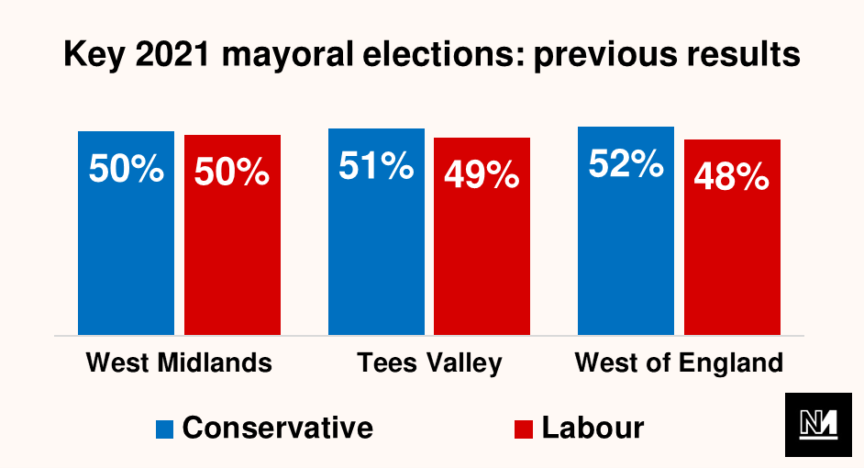

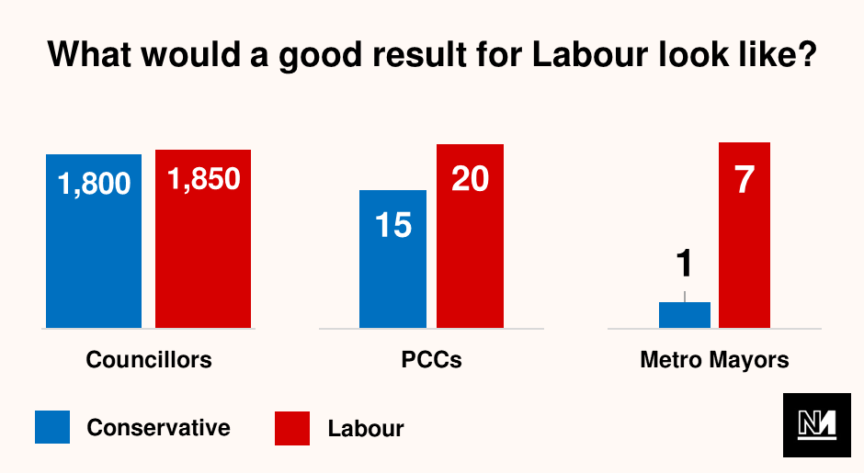

Local councillors aren’t the only roles that will be up for election, however. English voters will also elect regional mayors, and on a good night, Labour could achieve a decisive victory. Of the eight mayors up for election, Labour has a real chance of winning all but one. Labour will almost certainly win West Yorkshire and hold Greater Manchester, Liverpool and London; the key battlegrounds are the West Midlands, West of England and Tees Valley.

Labour could win all three, and together with its expected victories elsewhere, this would give Labour a landslide 7-1 victory. It’s a similar story in the PCC elections; the Conservatives won the most PCCs by a 20-15 margin in 2016, but Labour only needs a 4% swing to reverse that margin.

In Scotland, Labour has no real prospects of winning, having finished third in 2016. Returning to second place and denying the SNP a majority is the best Labour can hope for.

In Wales, Labour is seeking re-election after more than two decades in government; in that context, simply staying in government would be an impressive achievement. Whilst an overall majority is possible, it is unlikely, so a top-tier result for Labour would be to win 30 seats as it did in 2003 and 2012.

In summary, a respectable showing for Labour would look something like this:

What can we expect?

That’s what a good night for Labour could look like. Given that Labour is currently behind in the polls by an average of 8 points, what should we expect to actually happen?

39% of council seats were last contested in 2016 (when the Tories were 3 points ahead), 44% in 2017 (when the Tories were 14 points ahead). There has been a swing to Labour in some areas since then, but a swing away in almost as many others. My prediction would be that little will change in terms of council seats, with Labour gaining a few dozen, but less than 1% of seats changing hands overall (as in 2016 and 2018).

We can be slightly more precise with PCCs and Mayors. Since 2016, there has been a 3-point swing to the Conservatives, suggesting that they will gain between 4-5 seats. Meanwhile, there has been a 3-point swing to Labour since 2017, suggesting that Labour mayoral candidates will win back Tees Valley and the West of England. However, two recent polls show Labour losing the West Midlands Mayoral election.

In Scotland, polls suggest a small SNP majority with Labour coming third. Welsh polls, meanwhile, indicate that Mark Drakeford will return as first minister, leading a minority Labour government.

Conclusion

Opposition parties historically perform well in local elections. However, Labour has not won more than 80 seats in a local election since 2014. Meanwhile, the government is riding high, with Boris Johnson’s approval rating at its highest since last May. Not only that, but the areas up for election were last contested before Britain left the EU, many before Britain even voted to leave.

Keir Starmer was elected as Labour leader specifically because he was seen as the most electable candidate. Yet it is entirely possible that his first election as leader will be an embarrassing defeat. If so, the leadership will need to seriously rethink its strategy – because emphasising new leadership while offering little in terms of policy can only get you so far.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties and a columnist for Novara Media.