Johnson’s Government is Rotten to the Core – But Does It Even Matter?

Tory corruption scandals don't make other parties seem more appealing – they just evaporate faith in the system itself.

by Samuel Earle

4 May 2021

It says something profound about our prime minister – and indeed the nation that elected him – that, even as a schoolboy in the gilded corridors of Eton, Boris Johnson’s sense of entitlement stood out. In a now-notorious letter to his parents dated 1982, Johnson’s school housemaster complains of how the 17-year-old “honestly believes that it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception.” Johnson has, the letter says, “a disgracefully cavalier attitude,” and “seems affronted when criticised for what amounts to a gross failure of personal responsibility.”

Almost 40 years later and, as Johnson fulfils his childhood dream of leading the country, the same traits are plain to see. With his government suddenly subsumed in scandal, Johnson’s moral character – his sense of entitlement, his recklessness, his disregard for anyone but himself – is once again under scrutiny. He is reported as saying in October that he would rather “let the bodies pile high” than call a third national lockdown (though in his typical have-your-cake-and-eat-it fashion, it seems he decided to do both), and a costly and suspiciously-funded refurbishment of Downing Street has now attracted the attention of the Electoral Commission.

The two stories have put Johnson under unusual pressure, and his impetuous response shows he is very much the same schoolboy described by his Eton housemaster. At Prime Minister’s Questions last Wednesday, as he was repeatedly probed about the scandals, he teetered on the edge of a tantrum. Images of a raging, red-faced Johnson went viral online, as ‘angry Boris’ became a meme.

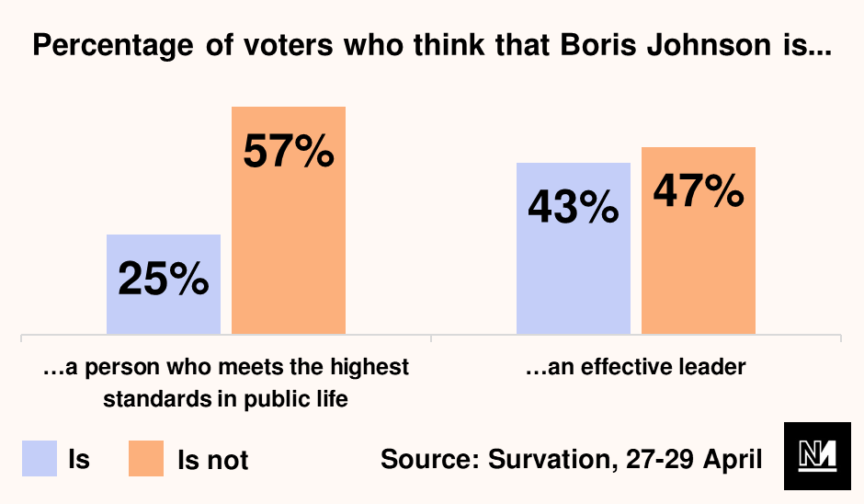

But while the left may revel in the rare spectacle of a Conservative prime minister being held to account – with the charge led, dizzyingly, by The Daily Mail – it would be a mistake to reduce the “stench of sleaze” currently emanating from Downing Street to Johnson’s odious character, or to see these revelations as any kind of mortal wound to his prime ministership. The controversies speak to much bigger problems at the heart of British politics, of which Johnson’s moral vacuity and his electoral popularity are grim symptoms.

A major reason why these scandals have struck a chord is not only their unlikely messenger, but that they fit a broader pattern. Johnson’s alleged comments crystallise his brazen handling of the pandemic, which has claimed over 150,000 lives. Meanwhile the flat renovation controversy – centring around a secret money transfer by multi-millionaire Tory donor Lord David Brownlow – is the latest in a long line of dodgy dealings. These include: assigning Covid-19 contracts worth hundreds of millions of pounds to friends and flunkies of Conservative MPs with no experience in the health sector; the likes of former prime minister David Cameron, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman and business tycoon James Dyson all enjoying a direct line to Downing Street to push their vested interests; the Greensill Capital scandal; the Jennifer Arcuri scandal; and so on.

Various names have been assigned to these revelations: ‘sleaze’, ‘cronyism’, ‘chumocracy’. But to many Brits, the most obvious word – ‘corruption’ – seems overblown. This is partly because in Britain’s gentlemanly self-image, the nation’s politics is uniquely clean: corruption is something that happens in other countries. On the rare occasions when politicians do cross a line, the tabloids often delight in emphasising – with pantomime rage – the quaint nature of the bounty. With the expenses scandal, for example, the most famous case was a Conservative MP claiming £1,645 for a floating duck house. Similarly, with the Downing Street refurb, the controversy is fuelled less by how it was funded and more by how much Johnson and his fiancé were willing to spend on wallpaper and curtains. What are they like!

But the reluctance to label these scandals as ‘corruption’ has as much to do with how we conceive of the term itself as how we conceive of Britain. We tend to imagine corruption as a matter of evil individuals exchanging suitcases of cash in dark rooms (bribery being perhaps the archetypal case). But as the political scientist Michael Johnston notes, there is a more quotidian type of corruption that happens in the plain light of day: elites acting to preserve and expand their power in ways that – via the workings of the press, politicians and the advertising industry – become accepted as the natural state of play. “In part because of corruption,” Johnston writes, “for millions ‘democracy’ means increased insecurity and ‘free markets’ are where the rich seem to get richer at the expense of everyone else.”

What counts as corruption, in other words, is a social question. So while Transparency International ranks the UK at an impressive 11 out of 180 for its low levels of corruption worldwide, it’s worth considering what isn’t included in this metric: the City of London being the world’s leading tax haven, for example, along with several of Britain’s overseas territories; the revolving door between Westminster, Fleet Street and the lobbying industry (of which Johnson, like so many of his colleagues, is a beneficiary); the banal process by which the likes of Lord Brownlow, along with 14 other Tory donors, are appointed to the House of Lords. We could also add to that list: the way a government can mismanage a pandemic, resulting in tens of thousands of avoidable deaths, with impunity. What word should we use for all this?

At the most basic level, all of Britain’s recent scandals share a single source: the cosiness of an elite bound by mutual back-scratching, the majority of which happens within the limits of the law. This cosiness is as much a feature of our political landscape as elections, and so there should be little surprise in what we see.

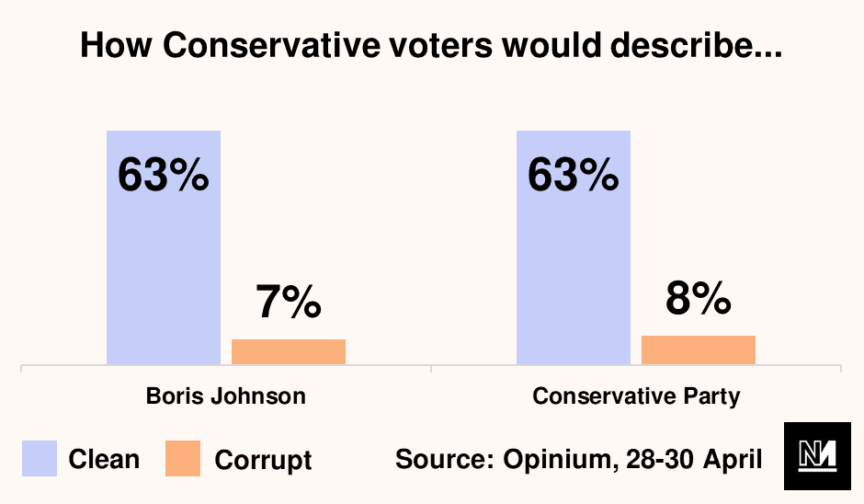

But it is one of the crueller consequences of corruption that the cumulative effect of exposure is not to make opposition parties more appealing, but rather to evaporate faith in the system itself. In a world where politicians are in it for themselves, the promise of a progressive Labour government is unpersuasive because people lose belief in the ability of any government to be a force for good. It is telling that when Johnson was questioned at PMQs on his Downing Street refurb, he invoked Tony Blair. The Labour prime minister spent far more on refurbishments, Johnson declared (omitting the fact that this was over a ten year period). The point was: we’re all as bad as each other – so what are you going to do about it?

This is politics for power’s sake, without hope or expectation – a context where Johnson, with nothing driving him beyond his own ambition, is right at home. His self-serving deceit isn’t the reason why levels of public trust in British politics are at historic lows; the void of trust is why Johnson’s untrustworthiness doesn’t matter: he is the ugly offspring of a broken political system. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word ‘corruption’ partly originates in the obsolete English ‘corrump’, meaning to decompose or rot. Johnson’s latest chain of scandals should remind us that the rot runs deep.

Samuel Earle is a writer based in London. His work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, the London Review Books and elsewhere. This piece is part of a series on the Tories and how they hold on to power.

Part one: Even Without the ‘Vaccine Bounce’, Boris Johnson Would Still Be Winning

Part two: Being an Opportunist Has Worked Well for Johnson. Why Not for Starmer?

Part three: By Stoking Britain’s Culture War, Boris Johnson is Playing the Long Game