Students’ Unions Are Demanding a Covid-19 Discount. They Should Be Demanding Much More

Students aren’t consumers who’ve been mis-sold a product.

by Sarah Cundy

8 June 2021

Last Monday, 31 May, 17 students’ unions wrote to education secretary Gavin Williamson and universities minister Michelle Donelan requesting a tuition fee rebate of 30% (or around £2,700), paid for by an increase in the student loan interest rate from 3% to 6.2%. The letter is striking, and not just for the timidity of its demand, but also its acceptance of the marketisation of higher education.

We’re disappointed that some SUs have taken the approach of demanding tuition fee rebates.

These demands strengthen neoliberal narratives which tie monetary value to learning.

We need free education for all and forever – not just during the pandemic.https://t.co/2NZw3eFW8I

— Green Students (@gpew_students) June 1, 2021

Since Labour introduced tuition fees in 1998, and particularly since the coalition government uncapped them in 2010, universities have relied heavily on student fees for funding, and so treated students increasingly as customers. Starved of government support, universities’ priority is to get as many students through the door as possible, often with little regard for the impact on teaching, research and the wellbeing of staff and students. High-paid bureaucrats use client satisfaction metrics such as the National Student Survey to justify forced redundancies, while students find themselves in full-to-the-brim lecture halls with dwindling pastoral care.

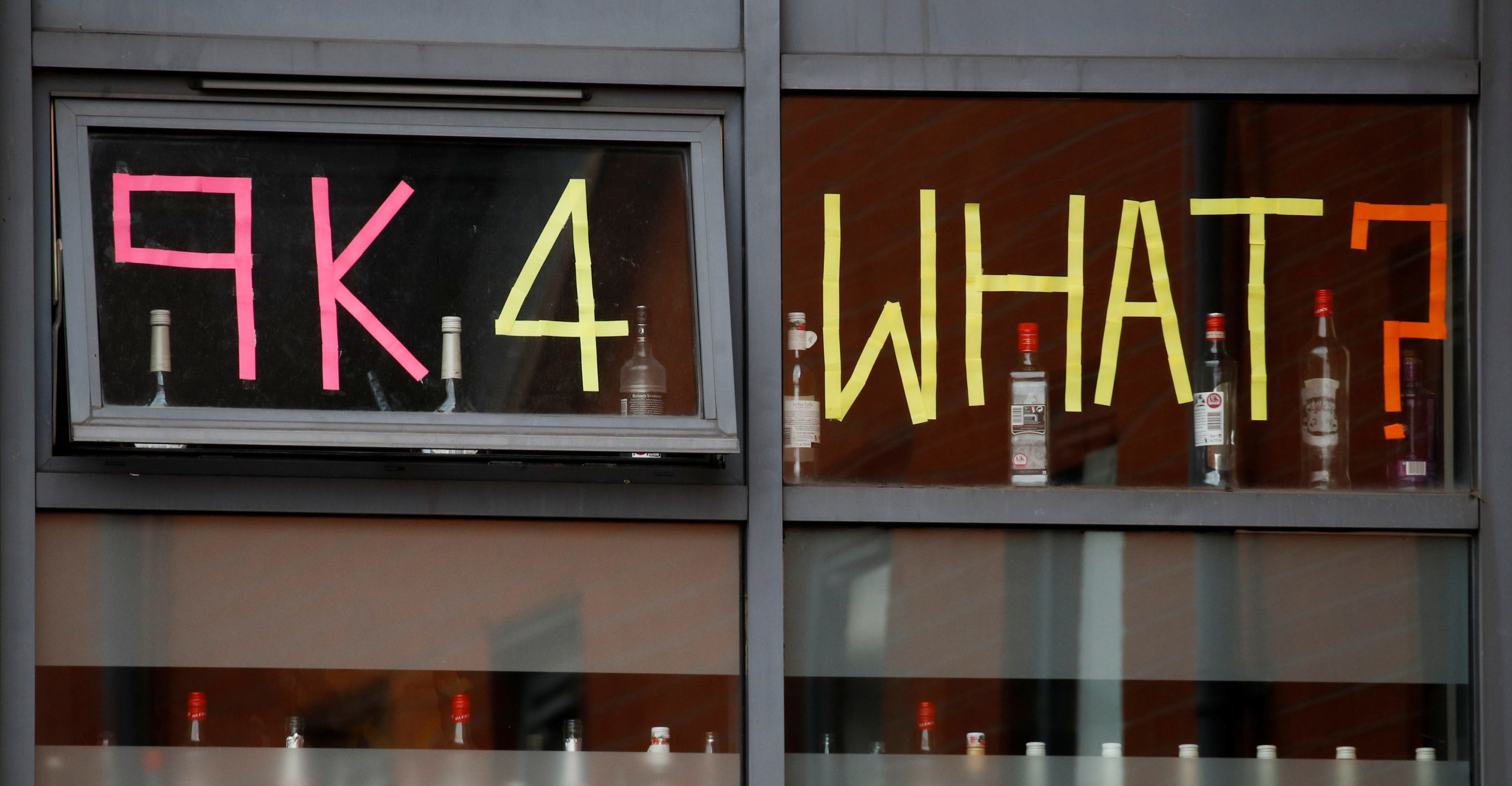

The pandemic has exposed the ongoing crisis of this system. Students have been made painfully aware of their status as cash-cows, lured back to campus by corporate landlords, university management and the government on the promise of “blended learning”, only to be marooned in unaffordable accommodation without economic, mental health or indeed coronavirus support. At the University of Manchester, students were literally fenced into their accommodation, while self-isolating students at Lancaster were charged £17.95 a day for food.

Students are paying £9k fees for the privilege of getting coronavirus, held hostage in halls, and lecturers who still can’t take themselves off mute. https://t.co/czO0hadf5c

— Ash Sarkar (@AyoCaesar) October 2, 2020

As this crisis unfurls, most students’ unions seem incapable of challenging the system responsible, instead buying into its logic. Speaking to The Guardian, David Gordon, general secretary of the LSE students’ union, described the group’s demand as “an attempt to find a constructive way to speak to the government about compensation after exhausting other avenues, including the Competition and Markets Authority, the Office of the Independent Adjudicator, … and the Office for Students.” Yet it’s unsurprising that none of these organisations – the latter of which was part-governed by Toby Young for a fateful day in 2018 – have intervened on students’ behalf. It’s also unsurprising that students’ unions believed they would.

The reason that student unions are so committed to complaining to the manager is that they have been co-opted by university management, and used to block student radicalism.

We have to come to terms with the immense violence NeoLiberal Student Unions perpetuate against students. Acting as the friendly face of an exploitative corporate machine, where students who criticise or attempt to subvert it, have the full weight of bureaucracy thrown at them.

— Read Black Marxism by Cedric Robinson (@decolonialcommi) February 12, 2021

The marketisation of higher education has inevitably implicated SUs’, who rely on university grants for their funding. Increasingly, such funding is funnelled into sports, events and facilities over political ventures that the government is making increasingly risky for students; the Conservatives recently announced that they will fine SUs for no-platforming. Where SUs were once sites of agitation, they are now more commonly sites of acquiescence, another line on your CV rather than an opportunity to make genuine change.

Not all students have sold out, however.

On the contrary, many have been radicalised by their experiences over the last year and a half. While SUs politely request a refund on their degrees, others are making more absolute demands. At the University of Manchester, hundreds of students tore down the fences within hours of them being erected.

Respect to the students of Manchester LG x

— Liam Gallagher (@liamgallagher) November 6, 2020

Yet perhaps the best example of the politicisation of students by the pandemic have been the rent strikes that have swept the country, being held in 55 of 140 UK universities – and in many cases condemned by students’ unions.

This sheds some light on the peculiar case of Bristol keeping on campus teaching…

Students union is actively lobbying for more time ON CAMPUS while #covid rates go up!

The neoliberal university at its worst – when ones own union puts consumption & ‘experience’ over health pic.twitter.com/y6BU5diRiH

— Victoria Canning (@Vicky_Canning) October 14, 2020

In Manchester, students last year won a 30% rent reduction, claimed to cost the university £12m – the largest concession in student rent strike history, while SU officers attempted to convince student organisers to call off the strike. When Manchester students later occupied one of the university buildings, an SU officer reportedly told occupiers they were simply doing the bidding of the University and College Union. They were partly right.

For while SUs have been pursuing narrow goals such as student refunds, many are choosing to participate in a broader struggle for higher education, one that requires them to defend others’ interests alongside their own. In the past two weeks, students at the University of Liverpool have joined online teach-outs and physical and virtual picket lines in solidarity with striking lecturers. At the other end of the Mersey, Manchester students marched to the university’s National Graphene Institute demanding that it end collaborations with Israel Aerospace Industries, an Israeli state corporation that develops the drones used to bomb Gaza. These students are acutely aware that the market’s assault on higher education operates on multiple fronts, and that they must be present on all of them.

Manchester students and community turn out for Palestine at @OfficialUoM yesterday, answering the @AOC_movement call to action! We demand from UoM: Break the links with Hebrew University! End Graphene Warfare! pic.twitter.com/LDETUldRUh

— BDS Campaign – UoM (@BDSUoM) May 29, 2021

As radical students organise outside the confines of the students’ union, university managers plan how to further integrate SUs into their corporate strategies. It is high time we abandoned these bureaucratic bodies to focus on building grassroots movements, articulating at every instance that this system is broken in its entirety, and we must rebuild it from the ground up.

Sarah Cundy is a history student at the University of Manchester and secretary of Manchester Labour Students.