‘It’s Only the Start’: George Galloway’s Bid for Batley and Spen Could Leave Starmer Staring Into the Abyss

'I don’t think he could survive a defeat to me.'

by Aaron Bastani

25 June 2021

In early May, George Galloway suffered arguably the greatest disappointment of his political career. The man responsible for two of the great upsets in modern British politics – triumphing in Bow and Bethnal Green in 2005 and then Bradford West in 2012 as a Respect candidate – founded a new unionist party which amassed a meagre 23,000 votes in the Scottish parliament elections.

As Galloway was digesting All for Unity’s abject defeat, Labour’s Keir Starmer was facing even greater problems. A stunning loss in the Hartlepool byelection, where the Tories triumphed by a margin of 7,000 votes, may have captured the headlines, but it was the collapse in the race for Tees Valley Mayor, as well as defeat for Liam Byrne in the West Midlands, which indicated that Labour has further to fall than their perceived nadir of 2019.

There remained some bright spots, however, including the election of Tracy Brabin as the inaugural mayor for West Yorkshire. The only downside was the party now faced yet another byelection in the marginal of Batley and Spen, which Brabin had represented since the murder of Jo Cox in 2016.

In the days following those results, as Starmer bungled a reshuffle and Galloway furtively returned to his home on the Scottish Borders, a group of businesspeople in West Yorkshire were determined to exert some political influence. Given the proximity of Batley and Spen to Bradford West, where Galloway delivered that shock win nine years ago, they decided to reach out to a man still best known for his opposition to the Iraq war.

Galloway was initially cold on the idea, with his humiliation in Scotland reflecting other poor performances in West Bromwich and Manchester over recent years. He decided to visit the seat in any case, and as he drove through Batley with his election agent James Giles, the resemblance to parts of Bradford became clearer. As they passed a chai shop with a small Palestine flag outside they were persuaded. “We just looked at each other,” Giles tells me, “and we knew George had to do it.”

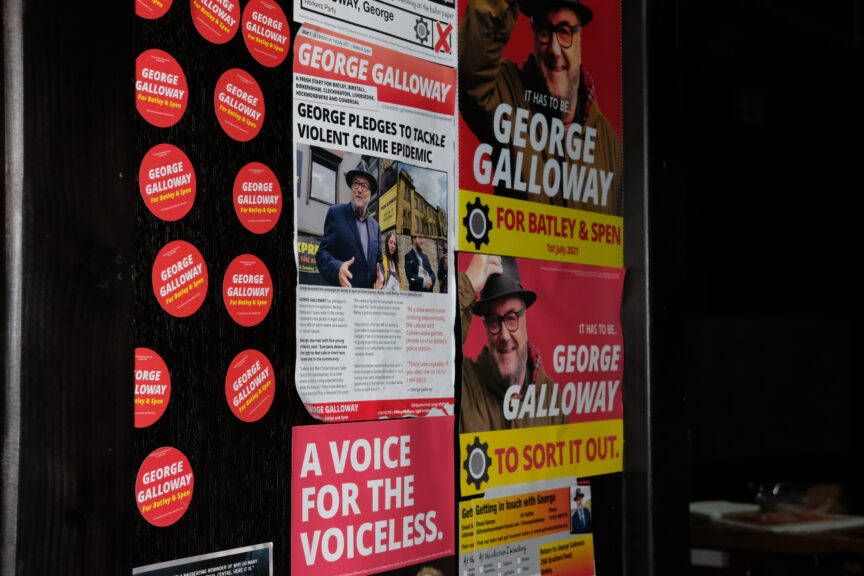

When I arrive a fortnight later, Galloway’s face is plastered across Batley – the largest town in the constituency. His campaign is being run out of three separate buildings donated by local industrialists. Talking to Giles – young, articulate and responsible for most of the campaign’s literature – I’m told the Workers Party has ten full-time organisers in the constituency (something I would not have believed had I not been there myself). Even Labour activists are open about Galloway’s effort being better resourced than their own. “If we weren’t here,” Giles says, “all the Tories would have to do (to win) is not fuck up.” He is confident that there are“no circumstances” under which Labour can retain the constituency come 1 July.

The issues.

Unsurprisingly, Batley and Spen is a more complicated constituency than media platitudes would have you believe. Held by the Tories until 1997, it is one of the more tenuous instances of Labour’s crumbling ‘red wall’, while its large Muslim population discredits cliches of post-industrial Britain having little interest in foreign policy or civil liberties. It is also varied: Batley, where Galloway’s vote is strongest, is very different to Cleckheaton – primarily white and tending Tory since the Brexit referendum.

While it may be politically diverse, the constituency has undoubtedly faced the full force of austerity. Batley and Dewsbury Magistrates’ Court closed in 2012, Dewsbury and District A&E was downgraded in 2017 and Batley police station shut in 2018.

While Palestine is a major issue, even Galloway concedes his priority has to be crime. “We had a politician murdered in broad daylight,” one former Labour supporter tells me, “not long after the police station closes – what signal does that send?” Galloway’s policy on the topic is simple: should he become MP he will try and reverse the sale of the former police station – recently administered by the local council – and should that fail a station will be opened elsewhere. Given Labour’s Kim Leadbeater is calling for more police too – and Batley station was closed as a result of Tory austerity – it might seem strange that some blame Labour for its closure. Yet it happened under the watch of the Labour-controlled Kirklees council whose priority, I am repeatedly told, is to divert funds to nearby Huddersfield. The dichotomy of town versus city, so troubling for Labour at a national level, can be found in microcosm here in West Yorkshire.

Indeed Labour’s apparent preference for Huddersfield is a recurring theme, and an issue happily seized upon by Galloway. “Where are we?”, one businessman funding his campaign rhetorically asks. “Our college got shut down, our magistrates got shut down, our hospital and police station got shut down. With the high streets, it’s all takeaways and charity shops. Batley and Dewsbury were lovely little towns. We know what the Tories are but Labour was supposed to be on our side.” Beside him, another businessperson, also supportive of Galloway, points to the condition of the town’s roads – which are notably poor – before describing how the council chose not to sell a painting by Francis Bacon valued at £20m. I later find out the city’s ownership of the picture means it forfeited the right to any proceeds in the event of a sale.

From saving services to supporting Palestine.

26-year-old campaigner Tanisha Bramwell demonstrates how both Galloway’s appeal and the disillusion with Labour extend beyond the local Muslim community. Previously a Labour party member, she quit to stand as an independent in May’s local elections, winning 620 votes in Dewsbury West. “I had some amazing youth workers [who turned] my life around,” Bramwell tells me. “That’s why I’m so passionate these services are brought back. I didn’t see any parties doing that.”

When I ask Bramwell – who was involved in delivering food parcels during the pandemic – why she didn’t stand as a candidate for Labour, she explains that the local party indicated the wait would be ten years. How Labour operates locally clearly still rankles, but Bramwell is also excited about Galloway’s platform – “his plans to improve the area locally are fantastic – it’s why I said yes to working with him”. Nevertheless, she remains pragmatic with an eye beyond 1 July: “I don’t agree with everything George has said and done – I’m helping him focus on local needs. We’ll still be here if he loses, building our organisation.”

Listening to Galloway later that evening, it becomes clear why many believe he can secure funding for local services. “It’s the squeaky wheel that gets the grease,” he says, implying a vote for him would mean resources are directed to Batley. For many, that means his celebrity persona, and even outsider status, isn’t a problem but an advantage. This is compounded by the perception that he was an able MP in nearby Bradford, with one local saying he was responsible for saving both the city’s media museum and its Odeon building. Separately, I’m told it was Galloway’s personal intervention that saw Bradford finally land a new Westfield development. While the former MP’s precise role in such outcomes is debatable, they are very real.

All of which means a candidate running to the left of Labour is enjoying support from unlikely places. One example of that is Lynne, a magistrate who worked in the NHS for 30 years, and who has previously voted for both Labour and the Conservatives. Sitting in her front room she describes Keir Starmer as “wishy-washy”, adding that Galloway, while far from perfect, is a “character” who did “great things for Bradford West”. One Labour figure she would vote for, however, is Andy Burnham: “I like him, he’s a go-getter”. Lynne embodies the complexity so often ignored in political punditry, having voted to leave the EU while being a passionate advocate for the NHS. Before I leave, she says working people deserve “dignity”.

There’s no denying, however, that it is Palestine that has made Galloway a plausible contender. “I would have been competitive (without Palestine), but I wouldn’t be talking to you about winning,” he tells me. One of his supporters said they simply wanted to send a message to the political class that “backing Israel without qualification has a price”. They add how they gave Starmer the benefit of the doubt over Kashmir – an early mistake from the leader just a month into his tenure – but the party’s response on Palestine, particularly given events there unfolded during Ramadan, was a step too far.

Another local businessperson, also backing Galloway, is even more critical of the Labour leader. “This guy refuses to say the word Palestine – now we have this opportunity to do something about it.” When I mention how Starmer recently raised Palestine in parliament, they claim he only did so as the prospect of defeat here became increasingly likely. Could they still be persuaded to vote Labour on 1 July? “It’s too late for that, the damage was done long ago.”

Alongside Kashmir and Palestine, many are also aware of Starmer’s refusal to participate in a digital Iftar with Omar Salha, CEO of the Ramadan Tent Project and supporter of the BDS campaign against Israel (boycott, divest, sanctions). “Keir Starmer is not fit to be Labour leader,” a local mufti tells me over a late-night chai. “He’s neglected Muslim voters, but it’s not going to be the same anymore”. Like many I spoke to, he was under no illusions about Galloway, or indeed any politician. Yet rather than party loyalty or a divide over ‘values’ – so frequently cited by liberal sociologists – what I encountered was a highly transactional view of politics. Simply put, increasing numbers of people can’t discern any benefit in voting for Labour. Given the government already has a majority of 80, what difference will one more Tory MP make? This will partly redound to Galloway’s benefit, but one also suspects many former Labour supporters simply won’t bother.

Galloway’s message.

The evening of my arrival, I join a canvassing session of around 70 people in Heckmondwike. Slightly fewer attend a subsequent meeting at 9pm. These are daily exchanges, I’m told, part wash-up, part pep talk, and the mood today is upbeat. “Edwin Poots is the first resignation this summer,” Galloway begins, “but he won’t be the last.” Importantly, there is an organisational aspect at work, with leafletting sessions outside school gates delegated among volunteers for the following morning. With two weeks to go, five schools are covered. The plan is to get that to at least double figures before polling day.

Galloway and his team predict turnout will be somewhere between 40% and 50%, and with 16 candidates on the ballot, they believe 16,000 votes could be enough to win. But despite rising hopes of a political upset – or at least a very strong third – the immediate ambition is constantly repeated: “Our mission will be successful the minute Keir Starmer has a leadership challenge,” concludes Galloway.

Perhaps of greatest concern for Labour is that those involved here, from the campaigners and local business community to dissident Labour members, view this byelection as a prototype. One of the individuals who initially asked Galloway to run tells me a network of like-minded people is emerging across Yorkshire, Lancashire and beyond. “What we are doing, everyone wants to copy […] they’ve asked us how can we get a good candidate to run.” Dissatisfaction with Labour, and particularly Starmer, is converging with ad hoc and increasingly professional efforts to exert leverage over national politics by appealing to both local and global concerns. “It’s only the start”, they continue. “If he doesn’t win here, there are ten other places Galloway can stand. And if he doesn’t win, it’ll still lose Labour the vote and they might start paying attention.”

Some even say such efforts could extend beyond Galloway. Over dinner, a younger member of one of the town’s business families tells me generational change is playing a part. “Our grandfathers voted Labour, but now we are saying it doesn’t have to be like that. There is less deference, we want to shape things.” The day before my arrival, five community groups wrote an open letter to Starmer clarifying how if the “needs and issues close to our hearts are not addressed,” local communities would “conclude that the Labour party no longer have our best interests at heart.”

That Friday, as I return south, Survation publish a poll putting the Tories six points ahead of Labour, with Galloway on 6%. From what I saw, such a result would be viewed as a failure by those around the former MP, with many considering a second-place finish entirely plausible. Even that doesn’t need to happen, however, for Labour to be staring into the abyss come 2 July. Whether its Brexit or Islamophobia, what’s clear is that its electoral coalition continues to balkanise, with this now accelerating as a result of Starmer failing to offer policies or even discernible political lines.

“I don’t think he could survive a defeat to me,” was one line from Galloway that stays in my mind. Perhaps more concerning for Labour is that Batley and Spen, rather than some terrible final reckoning, may represent another step towards historic irrelevance.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.