Scrapping Britain’s First Red Light District Will Be a Disaster for Sex Workers

Pushing workers into the shadows means putting them in danger.

by Lydia Caradonna and Kate Hardy

1 July 2021

Police in Leeds have decided that sex workers are “not welcome in Holbeck”, a managed zone where sex work was permitted from 2014 until the coronavirus pandemic hit in March 2020.

The zone had benefited sex workers, with an increasing number becoming comfortable reporting violence, but it is now set to be permanently scrapped following campaigns by anti-sex work ‘feminists’ and local residents, as property prices begin to rise in the area.

Sex workers and activists have condemned the decision, arguing that the zone has been successful in safeguarding sex workers. Indeed, within its first year, figures released by Leeds police showed that the number of sex workers reporting sexual violence had trebled. While critics point to this statistic as proof that the zone increases violence, sex workers argue that it actually indicates workers’ increased confidence in reporting violence without fear of retribution. Meanwhile, an independent review conducted by the University of Huddersfield concluded that the zone’s ‘managed approach’ was “more effective at reducing the impact of problems associated with on-street sex working than any other…model”.

Our thoughts right now are with sex workers in Leeds who will be less safe because of the permanent closure of the Managed Zone. Both sex workers and the local charities that support them opposed this decision. The groups who campaigned for closure are hateful and dangerous.

— SWARM (@SexWorkHive) June 16, 2021

The move to scrap the zone not only flies in the face of academic research, it also disregards the material realities of sex work. Time and time again, sex workers have attested to the dangers they face when any aspect of sex work – buying or selling sex – is criminalised. In 2006, Steve Wright was able to murder five sex workers in Ipswich as a result of the city’s ‘clamp down’ on street solicitation, which forced workers into isolated areas. While, at least 10 sex workers were killed in Paris in the space of just six months after purchasing sex was criminalised, with many forced to work in parks and forests to avoid their clients being arrested.

To understand why such a counterintuitive decision has been made in spite of the approach’s clear benefits, it is helpful to look at the work of Save Our Eyes, a campaign group that has been vocally opposed to the zone. Despite claiming to stand for safety, the groups intensely focused on the visual impact of prostitution. Its social media pages are littered with pictures of drug paraphernalia and condom wrappers. Far from being concerned about marginalised people working in dangerous conditions, Save Our Eyes’ main aim is to ‘protect’ middle class people living in Holbeck from the ‘unsightly’ physical evidence of sex work.

Every year thousands of items of sex industry waste are thrown onto the streets of Holbeck. The zone is currently closed – punters stay away! Photo taken this morning. @Child_Leeds @nordicmodelnow pic.twitter.com/bJMesX124d

— Save Our Eyes (@SaveOurEyes) June 5, 2021

The displacement of sex workers is nothing new – in fact, they are often some of the first victims of ‘regeneration’ efforts. Victoria Holt, a sex worker and member of sex worker advocacy group SWARM, draws a link between the closure of the managed zone and the violent brothel raids in Soho in 2016, as the area became gentrified. “Women were dragged out in their underwear and photographed by press who had been invited [by the police] to publicise the spectacle,” explains Holt.

“The partial criminalisation of sex work in the UK is used to justify forcibly removing sex workers from areas where they are considered to be less desirable residents,” she continues. “The properties from which [these] women were evicted – usually well-established walk-ups that were part of Soho’s history – were sold off and redeveloped into flats, stores and restaurants.”

What’s more, even legal sex work venues are being decimated by gentrification. Hackney, a traditionally working class, multicultural community, used to be home to a number of strip clubs. However, increasing gentrification in the area led the council to pass a ‘nil policy’, meaning it would no longer issue licenses for strip clubs. This, coupled with campaigns from groups like Object, who argue that sex work is ‘objectifying’, has led to strip clubs being erased from the landscape.

This kind of anti-sex work ‘feminist’ campaigning has also been crucial in clearing the way for a wave of urban development in Leeds. Such groups play on society’s existing anxieties around sex work (as ‘dangerous’ or ‘unclean’) as a means to justify the cleansing of poorer urban spaces. But for Paula Brown, committee member of the Save Our Eyes campaign, there is far more at stake; she is married to Nick Brown, the architect in charge of the Holbeck redevelopment. Her personal interest in the eviction of sex workers potentially speaks to a more cynical agenda: in clearing these spaces, Brown is making way for her capitalist gain at the expense of communities with little means to challenge or resist it.

Some local residents also support the scrapping of the zone in the hopes of ‘improving’ the area. Holbeck is becoming an increasingly expensive place and the zone’s closure will undoubtedly benefit businesses and some homeowners. But ironically, these rising property values may end up resulting in the pricing out of those very same residents currently arguing against the presence of street sex workers.

“It’s an unfortunate situation where communities and vulnerable groups are pitted against one another for scraps of social mobility,” explains a community development specialist and fellow of the Royal Society, who asked to be kept anonymous. “What communities like Holbeck need aren’t fancy £3 lattes, but real community investment in… infrastructure, education, youth opportunity, reproductive health and harm reduction.”

Women selling sex in Leeds won’t stop because you’ve taken away somewhere to do it. All closing the managed approach does is make it harder for women to report violence against them, harder to access support, & force them to work in secret. #KeepTheManagedZone

— Kate Lister (@k8_lister) June 22, 2021

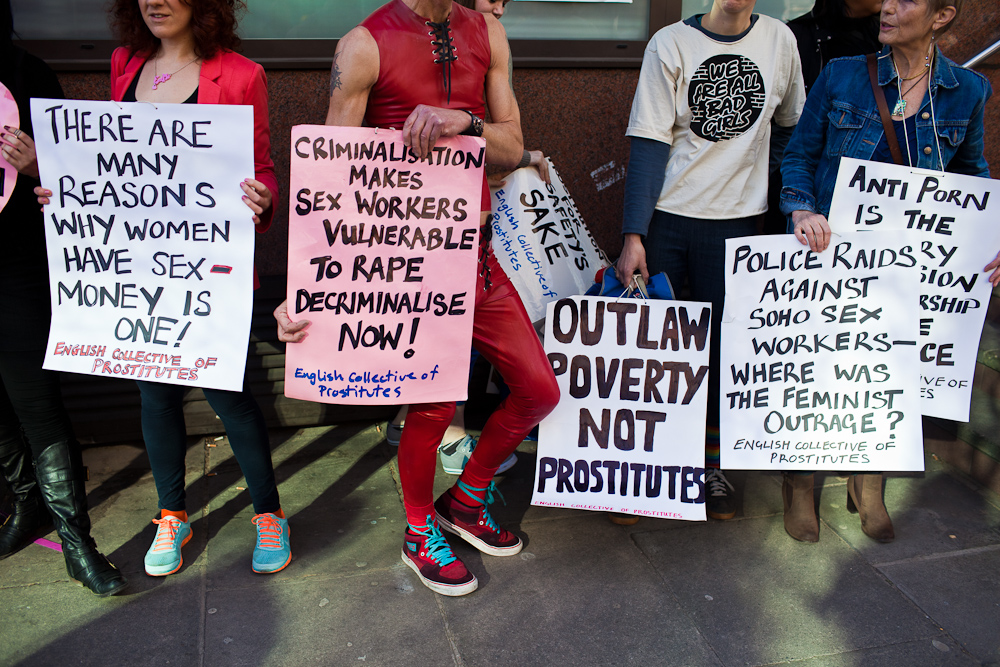

The loss of the managed zone is a disaster for sex workers’ rights. Yet, as the English Collective of Prostitutes argues, “a managed zone is no substitute for decriminalisation.” While this is true, a decriminalised workspace is only one part of the solution. Sex workers also need better labour rights, the power to collectivise and join unions and a social wage that enables them to better determine the terms on which they enter sex work and the decisions we are able to make within it.

With their workplace once again criminalised, the lives of Holbeck’s sex workers will be little improved by hipster coffee shops and luxury apartments. Returning to a prosecution and enforcement model will not reduce the number of sex workers, many of whom live in poverty or with complex mental health issues, limiting their options for employment. Indeed, the reality is that most sex workers will have no choice but to continue to work, regardless of the looming threat of fines and arrest – only now, that work will be less visible and far more dangerous.

Nick Brown Architects were approached for comment but gave no response.

Lydia Caradonna is a sex worker, writer, and community organiser. She is a founding member of Decrim Now and the UVW sex worker branch, as well as a member of SWARM.

Kate Hardy is an Associate Professor in Work and Employment Relations at the University of Leeds. She is feminist activist and founding member of Partisan Collective and Greater Manchester Housing Action, both based in Manchester.