Dave’s Latest Album Demands That Black British Music Be Taken Seriously

Guitar music doesn't have a monopoly on artistry.

by Kojo Koram

29 September 2021

We’re All Alone In This Together, British rapper Dave’s recent chart-topping album, makes a compelling case for why Black British music should be treated with the same intellectual rigour as the great British guitar albums of the past. It reminds us that popular music can also provide insights into the economic and psycho-social issues of today.

No cultural format attracted as much close examination during the mid-to-late 20th century as the pop music album. Once just a way to bind together a set of popular songs like a photograph album, the 1960s saw the long-play recording album become an artistic vehicle for transmitting big ideas to a mass audience.

The Beatles often receive the credit for reimagining the album as a space where musicians could convey a novelistic vision – although 1950s jazz albums like John Coltrane’s Blue Train and Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue trouble this chronology.

Still, The Beatles opened the door for the wave of genre-defining British albums that followed over the next few decades. The extent to which British artists punched above their weight in the US-centric music industry became a key part of the nation’s cultural identity. Litres of ink have been spilt by writers analysing the socio-political significance of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, The Clash’s London Calling or Radiohead’s OK Computer.

Radiohead’s OK Computer perfectly captured pre-millennial tension https://t.co/2wBS08IHv2

— Pitchfork (@pitchfork) July 21, 2019

However, as guitar music’s popularity has declined over the past few years, so has the level of intellectual attention being paid to the albums that now dominate Britain’s charts. Once confined to the marginal sub-genre of ‘urban’, music of Black origin – R&B, rap, grime, drill- have now become the most successful forms of music in the UK. Bands in skinny jeans have been replaced by tracksuited MCs, performers like Stormzy, J Hus and AJ Tracey, all of whom have produced chart-topping albums.

Yet despite the headline festival sets and Brit award nominations, the work that these artists are creating in this golden age of Black British music is not commonly approached with the same level of intellectual intensity as those which came out of the eras of, say, punk or Britpop.

One reason for the relative lack of engagement with recent Black British music is because its dominance has coincided with changing music listening habits. The technological shift from consuming music via vinyl records and CDs to streaming has transformed the industry. Streaming has accelerated the trend towards compiling playlists of your favourite songs rather than consuming whole bodies of work.

In a world where revenue mainly comes from live performance and selling hit singles to advertisers or film and TV soundtracks, artists and record companies are no longer incentivised to produce the kind of albums made to be poured over by listeners.

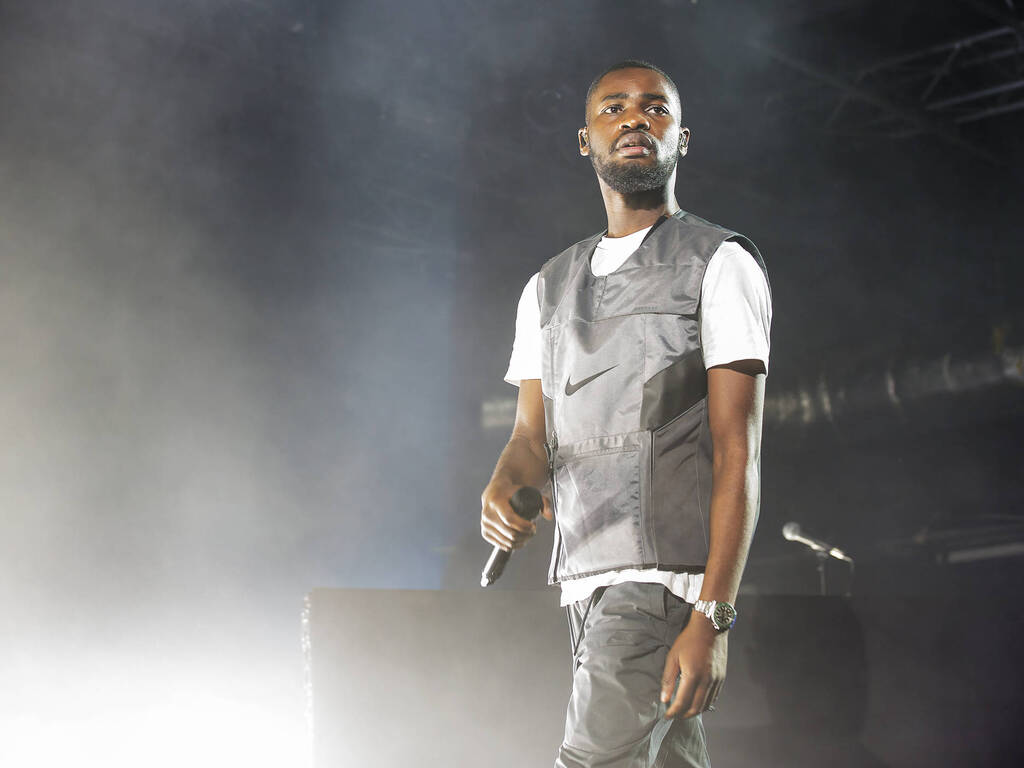

Dave’s music demands to be taken seriously.

But one musician certainly bucking this trend is south London rapper, producer and pianist Dave. The two albums he has created not only demonstrate his immense talent for making popular songs, but his ability to craft albums as comprehensive artistic statements that help his listeners to make sense of the society they live in. While Britain has produced excellent ‘political’ rappers before – Klashnekoff, Lowkey and Akala to name just a few – none have reached the mass audience that Dave has, making his music a cultural phenomenon that demands to be taken seriously.

Dave’s landmark debut album Psychodrama pushed the boundaries of rap. Both formally and politically daring, the concept album explores questions of violence, family and identity through the format of an experimental therapy session in which the narrator seeks emotional healing by way of reenactment of traumatic events from his past. Psychodrama broke new ground in revealing the vulnerability contained within the kind of young man we might expect to see in our newspapers under headlines about ‘knife crime’ or ‘gang wars’ – a man like Dave’s own brother Christopher, who is the inspiration for the album and currently serving a life sentence for murder.

Dave, a 21-year-old rapper from London whose family comes from Nigeria, has just won the UK’s Mercury Prize for his debut album, Psychodrama. https://t.co/fNQxv5xo1s pic.twitter.com/islp2ozsnB

— BBC News Africa (@BBCAfrica) September 20, 2019

Dave’s follow-up album, We’re All Alone In This Together, which was released in July 2021, expands beyond the solipsism of Psychodrama, alluding in its title to the collective isolation of the coronavirus crisis during which the album was produced. In other hands, this could have ended up reeking of crude opportunism, a desperate marketing ploy to try and ‘speak to the moment’. However, under Dave’s careful navigation, the album expands beyond our recent experience of isolation to consider enduring human issues of loneliness, relationship heartbreak, the alienation of fame and anxieties around race, class and gender during an era in which hypercapitalism is leaving us feeling alone and divided.

His influences are wide-ranging.

The album’s atmosphere of alienation begins to be communicated even before the music begins. The artwork is a reworking of Claude Monet’s classic work Impression, Sunrise, which is credited with inspiring the Impressionism movement – a movement that pushed the conventional rules of painting in order to try and capture the fluidity of life. Monet’s painting depicts the port of Le Havre at sunrise. Rowboats drift in the water, the misty port behind them and the sun rising overhead, signalling that a new day of industry has begun.

The cover art for Dave’s ‘We’re All Alone in This Together’ is inspired by the painting “Impression, Soleil Levant” (‘Impression, Sunrise’) by French artist Claude Monet. 🎨 pic.twitter.com/JIdRQnERpe

— Mic Cheque (@MicChequePosts) July 6, 2021

Dave’s album cover reimagines Monet’s painting, but drains the optimism from the scene. Now, there is just one boat, alone, floating on the sea that, along with the sky, has turned blood red. The rising centre of commerce that provided the background for Monet in the nineteenth century has seemingly self-imploded, consumed by a now never-ending ocean. With no shore in sight, the image no longer reflects the utopian promise of human movement; now it implies something far more apocalyptic.

The eerie isolation of the album artwork’s bleeds into the production too. Sonically, the record is sparse, seething and mournful. The spaciousness of the beats that have been composed for We’re All Alone In This Together add to the desolate atmosphere of the record, clearing a terrain in which Dave’s voice can take centre stage. As a rapper Dave was essentially a child prodigy, emerging as a lyricist seemingly fully formed at just 16 years old. But unlike other rap stars who broke through before adulthood – LL Cool J, Lil Wayne, Chipmunk or Dizzie Rascal – when Dave shared his voice with the world, it sounded nothing like a teenager’s. Even back then, he spoke with a deep, heavy baritone – already world-weary at a tender age.

Songs like We’re All Alone, Verdansk and Heart Attack maximise the impact of Dave’s powerful voice by allowing his sermons to be delivered free from any accompanying hooks or features, which can have a dampening effect on instrumentals. This serves to amplify the weight and spite of his vocal intonations, sonically emphasising this sense of isolation and his anger about it.

He meditates on capitalism.

On his latest album, Dave’s spite is pointed at the world at large. However, at first, it seems that he has little to be angry about. The boy from Streatham we met on Psychodrama has now been replaced by a globe-trotting, nouveau riche celebrity. The album’s lyrics are saturated with references to the rewards that success under hypercapitalism can bring you. He brags about the sheer material excess in his life, “Jordan 4s or Jordan 1s, Rolexes, got more than one,” and tells us how, since the success of his first album, his life has scaled up. Now, “the flight is to Santorini, the car is a Lamborghini, the cheese, the cheddar, the mozzarella, the fettuccini”. In a world in which the one percent are sailing further and further away from the rest of us, Dave has, against all odds, managed to clamber onto the last yacht out of Saigon.

That said, the celebration of his newfound riches comes with reservations. Despite the material wealth he has accrued, it is not enough to soothe his troubled psyche. Regardless of whether he is driving a Lamborghini or a Ferrari, he still finds himself “on the motorway, cryin’ in the driver’s seat”. Following the likes of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, who developed Karl Marx’s idea of commodity fetishism to show that, in addition to the hidden human relations that produce our commodities, capitalism also creates the internal feelings of emptiness that we hope to address by purchasing consumer goods, Dave spends the album locked in Baudrillard’s prison of “circulation”. He chronicles his frustration at the inability of material wealth to solve his feelings of alienation, until despondently confessing that “the money can’t buy nothing when the love’s done”.

Indeed, Dave learns that while he might be among the one percent, he is ultimately not one of them. Barriers of race, culture and background remind him that his wealth is contingent and precarious. He is an interloper in this world of ostentation, a 21st century, south London Jay Gatsby. Sure, he has the cash to be able to buy whatever he wants, but there is still a colour line that limits his access to exclusive spaces. When he wants to rent a mansion for him and his friends, “it’s a white man’s face that I use to book”- because if the owners saw what he looked like, they would likely turn him away.

This wealth, far from merely isolating him from his super-rich peers, has also served to cut him off from his family and friends, with Dave asking, “What’s the point of being rich when your family ain’t? It’s like flying first-class on a crashing plane”. There isn’t enough money in the world that can allow Dave to erase his family history of poverty, imprisonment and violence at the hands of brutal border regimes.

He explores what it means to be an immigrant.

Dave grapples with his background as “the child of an immigrant” more explicitly on this album than its predecessor. On the soul-stirring In the fire, he recounts the horrors of the UK immigration system, recalling how immigration officials threatened the family with deportation when he was a baby, taking him “from my mum’s arms”. Meanwhile, on Three Rivers, Dave explores the isolation of living in a country that won’t accept you, asking what you should do when “the only place you live says you ain’t a Brit”. By exploring the experience of three different generations of immigrants who have come to the UK, Dave shows the complexity and humanity of the people all too often dismissed by the establishment as a faceless horde invading our island nation.

These ideas come to a head in Heart Attack, a 10-minute epic that concludes with what must be one of the most harrowing moments to have ever appeared on a number one pop album. Dave’s extended acapella monologue gives way to a recording of his mother recounting her early years trying to survive in England as an impoverished 20-year-old Nigerian immigrant with young children and an abusive husband.

In it, she tearfully describes the lack of support she received as an immigrant, from being stuck in detention camps for months on end, being homeless, carrying her babies across the streets of the UK – all while living with the constant fear that her husband was trying to kill her. Her anguish forces the listener to confront the reality of what so many of the people who sustain their daily lives in globalised cities like London have gone through just to live here.

Why did he put his mum sobbing into a song? “Sometimes I wonder if it was right to include it. But that pain? My mum is a good person. A nurse. She don’t trouble nobody. People need to hear it.”

📸 Andrew Timms pic.twitter.com/6jv3BVjSYv

— The Sunday Times (@thesundaytimes) August 8, 2021

What are the stories behind the cleaners who maintain our gleaming corporate offices, the taxi drivers who transport us across our cities or the Deliveroo workers who kept the nation fed during the pandemic? Immigrants continue to sit at the lowest rung of the economic chain that continues to drive such inequality across the world. They are the most easily exploited people within our society and the market discards them once they are deemed of no further use.

The pandemic gave a lot of us just a brief glimpse into their lives as we were trapped in our houses for months on end and forced to mourn family members from afar, unable even attend their funerals. With the future promising only more compounding crises to come, as the climate crisis, migration crisis and economic crisis are all set to intensify, Dave implores us to reimagine how we treat the most disposable members of our society, lest we find ourselves in their shoes.

He embraces the collective.

With the album painting such a bleak picture, where can the listener look for salvation? Must we all hope to follow Dave and try to make the impossible leap from the increasing precariousness of late-capitalism into the dwindling safe haven of the global super-rich? There is not enough space onboard there and even if we were to somehow make it, this album lets us know that it would never feel like home.

No, our only hope is in collective action. Dave’s very last words on the album are “in this together” – a smart and ultimately far more authentic subversion of David Cameron’s hollow slogan for how Britain should respond to the 2008 financial crash. Of course, while he pontificated about unity, the Tories were also implementing policies that imposed brutal austerity measures upon the majority of the country, whilst the wealth of the elite not only recovered but increased.

Dave uses his latest album to map out his traversion of this unequal world, from the detention centre to the private jet, “from no fixed abode to the coast of Greece”, discovering that whilst money has provided some insulation from life’s precarity, it has also contributed to making him feel even more estranged from not only others, but himself. On this journey, he reminds us that the age of the album isn’t dead; that there are still artists out there who see it as a medium to convey complex and challenging ideas to their audience.

He leaves his listeners with a lesson he has picked up on his travels: that despite our individual struggles, our only hope lies in our ability to recognise that, on this earth, we are all, ultimately, in the same boat.

This is the fifth and final article in Contesting Culture, a new series asking who really owns British culture. Read part one, part two, part three and part four here.

Kojo Koram is a reader in law at Birkbeck College, University of London and the author of Uncommon Wealth: Britain and the Aftermath of Empire.