Could Labour Lead Wales to Independence?

‘If anyone delivers a referendum on independence, it’ll almost certainly be the Welsh Labour party.’

by Aaron Bastani

6 October 2021

As the curtain fell on the twentieth century, the United Kingdom was one of the most stable countries on Earth. A member of the European Union since 1973, it had seemingly emerged from its colonial era, concurrent with the very invention of Britain, as a society capable of cyclical renewal. The partition of Ireland endured – though even here a breakthrough came with the Good Friday Agreement – but the island of Britain, in particular, seemed destined to remain much the same as it had been since 1707: an indivisible union.

Two decades on and few surveying the political landscape would reach that conclusion today. Britain voted to leave the EU in 2016, becoming the first member-state to depart earlier this year. At the same time, two of the last four Westminster governments have been volatile coalitions while, perhaps most significantly of all, changing dynamics beyond England means the union itself faces existential challenges.

This is most obvious in Scotland, where an increasingly dissident political culture has emerged. Despite the unrivalled supremacy of the Scottish National party (SNP), it’s important to remember just how recent its rise has been. A decade ago it boasted just six seats in the House of Commons, yet after the 2015 general election, it held 56 of a possible 59. Today, polling for independence puts ‘yes’ either ahead or behind by the margin of error. One poll in September put the SNP on 51%.

On initial inspection, the situation in Wales couldn’t be more different. Where the SNP has soared in recent years, the party of Welsh nationalism, Plaid Cymru, has stumbled. And while Scottish Labour suffered an inexorable decline from the early 2000s until its collapse six years ago, Welsh Labour garnered half of all Senedd (Welsh parliament) seats in the May 2021 election. The indisputable figurehead of Welsh public life is Labour’s Mark Drakeford, with the first minister more popular in Wales than Nicola Sturgeon in Scotland. If a necessary precondition for independence is the demise of both the Conservatives and the Labour party, as happened in Scotland, then prospects for any Welsh departure seem remote.

Labour for independence?

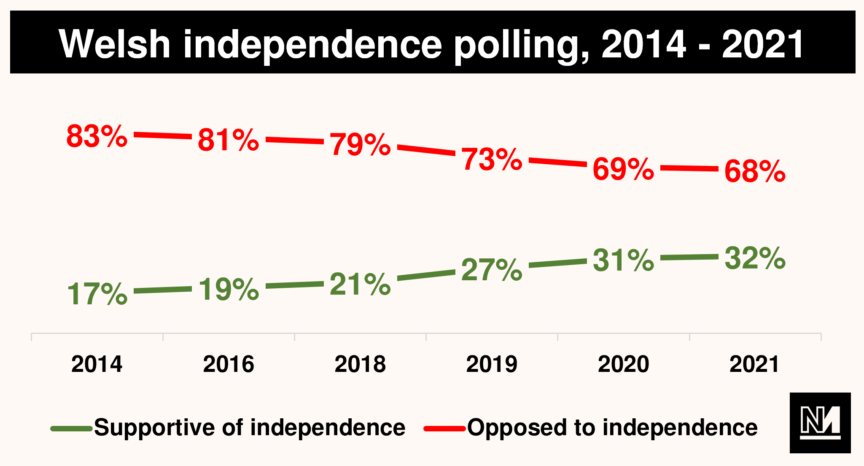

Yet despite the abiding success of Welsh Labour, with its commitment to the union, advocates for independence are no longer confined to the political margins. One recent survey for ITV found that, excluding ‘don’t knows’, 39% of respondents would vote for an independent Wales. While this is a single data point, the trend – as seen below – is obvious.

This shift in public opinion is all the more interesting given that the appetite for devolution, when initially offered in 1999, was underwhelming. In that year’s referendum on a prospective Welsh assembly, the yes campaign won by fewer than 7,000 votes on a turnout of 50%. Further back, the 1979 referendum on devolution garnered just 20% support. Today, by contrast, the overwhelming majority of people in Wales not only support devolution but think it should go further, with one poll putting support for ‘devo max’ – an option that stops just short of independence – at almost 60%, a figure which rises to 82% amongst 18 to 24-year-olds.

But if Wales isn’t content with the constitutional status quo, and desires greater autonomy, this begs an important question. What is the terminus for such a politics? And where does that leave Welsh Labour – dominant for a century – given the national question all but extinguished the party in Scotland?

20-year-old Dylan Lewis-Rowlands is a politics student at Aberystwyth University. In May, he ran as the Labour candidate for Ceredigion, a Plaid Cymru stronghold. Aside from his youth, what makes Dylan unusual as a party candidate is his support for independence. “The UK that created the NHS in 1945 doesn’t exist anymore”, he tells me – but in Wales, he says, socialism is still possible.

“Wales is creating a distinct identity and has a distinct body-politic,” Dylan continues over tea in a Pontypridd cafe. “We are perhaps 30 years behind Scotland, but Wales is becoming politically different. And that’s not because of Plaid Cymru – it’s because of Welsh Labour”. Unlike in Scotland, where Labour was a casualty of nationalism, in Wales it remains a beneficiary, Dylan concludes. As a result, he believes Labour can lead the argument for independence, rather than be left behind by it.

While by no means representative on the national question, Dylan is far from unique; two other Labour candidates for the Senedd elections in May held similar views. In 2017, party members set up Labour for an Independent Wales, a campaign group for those who “believe the best way to achieve a democratic socialist Wales is through independence”. Far from indulging in abstraction, its members in local government have already begun to pass motions supporting independence, beginning with the Labour-run town council of Blaenavon in late 2019.

While support for independence would be expected in the north-west, the heartland of Welsh nationalism, it is significant that parts of the south-east are following suit, with Caerphilly town council passing a similar motion to Blaenavon. While the council there is controlled by Plaid, the vote was unanimous, suggesting consensus on what one might presume to be a controversial subject.

Rather than departing from party tradition, Dylan tells me how supporting Welsh independence is in keeping with Labour’s founding values, with Keir Hardie – its first-ever parliamentary leader – advocating for home rule more than a century ago (although this applied to Ireland and Scotland rather than Wales). A more recent precedent was set by Elystan Morgan, a former Labour MP for Ceredigion and a prominent supporter of Welsh independence.

Rather than an eccentric minority of activists, shifting views on independence among Labour members reflect broader changes in the party’s electoral base. One poll found that more than half of Labour’s 2019 voters (minus ‘don’t knows’) now favour leaving the UK – almost on a par with Plaid Cymru voters. What’s more, 66% agreed that the Senedd, rather than Westminster, should have the power to call a referendum – a higher figure than amongst even Plaid voters (59%). In every age group, there was a majority or plurality for such powers resting with Cardiff – except amongst those over 65.

Few could have predicted that Labour voters would seemingly become as serious about independence as the party of Welsh nationalism. So is it possible that the tension between a party machine that champions the union, and an electoral base increasingly ambivalent about it, could doom first minister Drakeford, or more likely his successor, to the same fate as Scotland’s Jim Murphy?

Mark Hooper is the founder of Banc Cambria, a community bank set to launch later this year. For him, the prospect of history repeating itself is unlikely, with Welsh Labour’s blend of “soft nationalism with some social democracy” – as well as superior personnel – shaping a very different dynamic.

“Scotland’s best performers always went to Westminster – (Gordon) Brown, (Alistair) Darling,” Hooper says. “In Welsh Labour, things are different.” Drakeford’s political instincts are the epitome of this. In 2002 he wrote former first minister Rhodri Morgan’s cornerstone “clear red water” speech, which sought to delimit a Welsh approach to public services. That owed more to the “traditions of Titmus, Tawney, Beveridge and Bevan than those of Hayek and Friedman”, as Morgan said at the time.

Despite being a Plaid member, Hooper is optimistic that Labour’s stance on independence can change. “We don’t have to wait for Scotland or Brexit – this is about us recognising there are big issues we can solve in Wales,” he says. “Fundamentally that’s the message of both Labour and Plaid.” Because there is a growing consensus around further devolution, an SNP-style breakthrough for Plaid looks unlikely.

Above party politics.

So the independence movement is stirring, while its historic champion – Plaid – is listless. It’s no surprise, then, that independence campaigns are emerging beyond party boundaries.

“I don’t believe party politics is the way to solve this”, Hooper says. “Politicians will follow a grassroots movement that is pushing for independence”. Explicit or not, that sounds like a Gramscian strategy for independence, with the emphasis placed on changing civil society and public opinion before anything else. Again, this offers a contrast with Scotland where, until the last few years, a single party – the SNP – had been the vehicle for independence. While the likes of Commonweal and the Radical Independence Campaign (RIC) thereafter became major players, not to mention the Scottish Greens, they joined a movement rather than starting it. Whether the Scottish model has an advantage or not remains to be seen.

At the head of an undeniably insurgent movement in Wales is Yes Cymru, officially launched in 2016 and seemingly modelled on the Scottish Independence Convention, which emerged in 2005 as a cross-party platform to support an independent Scotland. Over the last 18 months, its membership has grown from fewer than 2,000 to 19,000 members.

Harriet Protheroe-Soltani is an organiser for Yes Cymru. While she speaks in a personal capacity, her story is illustrative of how views on independence have changed in recent years. Born and raised in Merthyr Tydfil, it was while studying in Edinburgh that she was first exposed to the idea of independence as a political project rather than an abstract idea. Initially, her instinct was to defend the union. “It’s embarrassing now, but I didn’t want Scotland to leave us in a rump with England,” she says. Eventually, however, Harriet was persuaded of the case for independence, not only for Scotland but Wales too. “I was convinced that socialism just isn’t possible through the union”.

Like other younger activists I meet, it’s easy to see how Harriet could have been sucked into London or the English south-east a few decades ago. “If you told me I’d be thinking about moving back to Merthyr when I was younger, I wouldn’t have believed you,” she tells me. A combination of technological change – particularly around remote working – a cost of living crisis generated by exorbitant rents, and an exciting political movement has changed all that.

Another referendum, this time on Britain’s membership of the EU, meant a second shift in Harriet’s politics. “When leave won I realised I was […] in a bubble,” she says. “The world I was in wasn’t very representative of the working class communities I’d grown up with.” At the same time, although increasingly sceptical of social democracy within the union, she joined the Labour party to vote for Jeremy Corbyn. “For me, Corbynism was the last throw of the dice,” she says, “but I also thought he offered politics closer to people, which is what I still want. You have to give that a punt.” Corbyn’s treatment by the London media and his parliamentary colleagues hardened Harriet’s views on independence. “The British state is antithetical to socialism. The monarchy, Westminster, the media, it’s all in complete conflict with what socialists want – we need to wipe the slate clean”.

So why does Harriet remain a member of the Labour party? Like Dylan, she believes it can champion independence, or at the very least a large number of its representatives could join a broader bloc that wins a referendum. “If anyone delivers independence or a referendum, it’ll be the Welsh Labour party,” she tells me, though she knows that will entail a fight with the party at Westminster. “You can already see the tension between Welsh Labour and Westminster – look at the debate on UBI”. Does that mean Welsh Labour could end up in a similar situation to its Scottish counterpart? “I just don’t see that happening for now”.

Despite being a member of Plaid, Llywelyn ap Gwilym, a member of the Yes Cymru central committee, adopts a similar tone. When I ask the former management consultant what distinguishes him from indy-supporting Labour voters, his reply is immediate: “nothing”. So why isn’t he a Labour member? “Look at Corbyn – he was arguing for a German settlement really, nothing that radical, and look what they did to him.” For Llywelyn, the horizon of possibility is far more promising if questions of distribution and government focus on Cardiff rather than London. Despite confessing that he initially supported independence for cultural reasons – his parents met through Plaid – the arguments he makes are no different to Harriet’s and Dylan’s: socialism is only possible through independence.

Llywelyn, despite not being a Labour member, agrees that the party in Wales is different to that in Westminster. “You can’t compare Stephen Kinnock and Chris Bryant to Labour members of the Senedd,” he says. What’s more, he acknowledges the party has made “massive steps” forward in recent years, noting how Labour standing three pro-independence candidates in May was “unimaginable” five years ago

Llywelyn offers one explanation for the rapid shift towards independence, both across Welsh civil society and within Labour: “Since Covid, people know that we [in Wales] have a government now, and there are things that we have control and power over”. Furthermore the enhanced visibility of Drakeford as a political figure – an anti-Boris Johnson for much of the public – has made thinking of oneself as politically Welsh increasingly normal.

But besides recent changes as a result of the pandemic, an aside from Llywelyn speaks to a deeper trend. While Welsh is Llywelyn’s second language – he was raised in England – he speaks Welsh to his son. This is emblematic of how the language was resurrected during the twentieth century – an era when cultural differentiation, and later devolution, emerged to challenge the status quo. Support for independence increasingly spans beyond Welsh speakers, but it is undeniable that greater prominence of the language in public life has played a part.

While Llywelyn is an older millennial in his late thirties, Merlin Gable is a decade younger and recently returned from England. He studied at Oxford University and, like Harriet, it was his experience beyond Wales which confirmed a greater identification with his Welsh identity. “My time at Oxford made me react very strongly against a certain form of English culture”, he explains.

Merlin remembers being a first-year student in 2014, during the Scottish independence referendum. “In those conversations, English people didn’t know what was at stake and I felt I did. The idea of Scotland being a country just wasn’t understood.” At the same time, Merlin felt Wales was developing an increasingly distinct political culture, with emigration to England less attractive as a result. Fewer opportunities across the border, a perceived fracturing of the social contract within the union, and this growing sense of possibility is why, for Merlin, the idea that Wales should generally govern itself is “now the orthodoxy for young people”.

Recent developments in Wales’ media landscape appear to confirm that. While a strong indigenous media has long been absent, with most UK newspapers not even producing a Welsh edition (as is common in Scotland), that is now changing. In 2017, Nation.Cymru, which describes itself as an “English language national news service for Wales”, was launched. 2019 saw the launch of Voice Wales, while The National – which also has a weekly print edition – arrived earlier this year. Some of these ventures will no doubt fail, but the trend would appear to indicate that basic changes in Welsh civil society are starting to be reflected in its media.

Another front in the struggle for independence is social media. Given younger voters are more disposed to independence, it’s no surprise that the platform of choice is TikTok, where there are presently 2.3 million posts under the #YesCymru hashtag.

https://www.tiktok.com/@indymarcus/video/6900347213105401089?sender_device=pc&sender_web_id=6899491607239230981&is_from_webapp=v1&is_copy_url=0

Contrary to the cliche that online conversations rarely translate to real-world impact, these thickening networks have been accompanied by offline activism, from petitions to the increasingly ubiquitous stickers of ‘Yes Cymru’, to demonstrations. All Under One Banner Cymru, founded in 2019, aims to coordinate marches across the country. Before Covid-19, three events took place in Cardiff, Caernarfon and Merthyr Tydfil, with the rally in Caernarfon attracting 10,000 people. There are already plans for more later this year, and organisers believe that far larger rallies, as in Scotland, are inevitable.

What next?

The consensus amongst those I spoke to is that a referendum during the next decade isn’t only possible but preferable, with 2028 repeatedly offered as a plausible date. At the same time, however, it was widely recognised that a long journey lies ahead, and building a political space distinct from Westminster remains the priority. For now, that means those who support independence – regardless of party loyalty – can carry on as fellow travellers, alongside the majority who simply favour greater devolution.

How the movement will unfold over the coming decade depends on a number of contingencies, but one can increasingly discern the conditions under which a Welsh departure might happen. In the event of another referendum defeat for the independence movement in Scotland, everyone I spoke to was clear that the odds of Wales’ separation would plummet. By the same token, if Scotland voted for independence, that would be a game-changer for Wales – particularly amongst those who are presently ambivalent about the matter. “Nobody wants it to be just us and England,” as one Labour member put it to me.

Second is the issue of Drakeford’s successor as Labour leader in Wales, with the light, folksy touch of the first minister, alongside his blend of “soft nationalism and social democracy” key to Welsh Labour’s success in May. Labour’s popularity in Wales would likely come under threat, however, if Keir Starmer attempted to install a preferred candidate or interfere as he did in Scotland with Richard Leonard. If the Westminster party did try to impose Drakeford’s successor, “there would be riots,” says Ceri, a Labour member from Swansea.

It would certainly show hubris from Starmer if he thought he knew better. To highlight the party’s differing fortunes across the two nations, Ceri relays how the same week Labour lost a council by-election in Leicester, they gained 80% of the vote in the Rhondda Valley. Indeed as a step towards independence, and to guard against political interference from London, some members are beginning to demand an independent party. As Martyn, a member from Ystradgynlais, puts it: “Why should I trust the party on federalism when the party itself isn’t federal?” For Dylan, the objective should be a sovereign Welsh conference that makes its own policy. “Before independence, we could still aim for zero-carbon or an anti-nuclear position.”

The third contingency is the Conservatives, and in particular Boris Johnson’s premiership. A reforming Labour government that delivers on federalism, however unlikely that may seem at present, would likely impede further progress for the cause of independence. Yet it is precisely because this is viewed as improbable that separatist sentiment is on the rise. As long as the Tories are in No. 10, especially with a prime minister as culturally outlandish as Johnson, support for independence will only increase. The same is true if Labour fails to offer a coherent agenda on constitutional reform.

The ideal conditions for independence, therefore, look something like this: in the aftermath of Covid-19, a distinct Welsh politics continues to materialise; Scotland holds a referendum to leave the UK and succeeds; Welsh Labour remains open to the possibility of constitutional change and the Tories stay in power. This, of course, begs the question of how a Westminster government would permit either Celtic nation to leave, but one suspects these are the conditions that need to be met. Even Drakeford himself has conceded that Wales’ place in the union would have to be “reassessed” in the event of Scottish departure. What’s, more, he maintains that any decision on future referenda resides with Glasgow and Edinburgh, not London.

“Many of the people who will drive and campaign for independence can’t even vote yet,” Dylan tells me towards the end of our conversation. Without a doubt, it is younger generations who will propel the independence movement to even greater prominence over the coming decade.

The Welsh Marxist Raymond Williams viewed independence as a process rather than an event, describing it as a “time of new and active creation: people sure enough of themselves to discard their baggage; knowing the past is past, as shaping history, but with a new confident sense of the present and the future.” Once already before, the Welsh people have achieved something similar, reviving their mother tongue after the middle of the twentieth century. That experience, of slow, incremental change – a ‘long revolution’ as Williams might have called it – has prepared many for the task ahead. “When we grew up the Welsh language was considered dead,” says Pat, a Labour member who thinks Wales could be independent within a decade. “Since then it has built and built”.

If a language can be reborn, and a Senedd emerge – then why not a sovereign Wales? Given the breakneck changes in Welsh politics and society over the last two decades, only a fool would bet against it. The question for Welsh Labour, meanwhile, is whether the politics of social democracy, let alone socialism, are best served in or outside the union. As the Westminster party moves right once more, and the Tories eye another decade of power, the answer for those who favour the union from a position of pragmatism could become increasingly discomforting.

This piece has been translated into Welsh by Emyr Humphreys. You can find the Welsh version here.

Breaking Britain is part of Novara Media’s Decade Project, an inquiry into the defining issues of the 2020s. The Decade Project is generously supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (London Office).

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.