Who’s More in Touch With Voters, Labour Members or Labour’s Leader?

In opposing the left, Keir Starmer risks alienating the very voters he needs to win.

by Ell Folan

12 October 2021

During the Labour party’s 2021 annual conference, delegates voted to back a series of bold policies to tackle the challenges facing Britain. Labour members voted to back a £15 minimum wage; a “socialist Green New Deal”; public ownership of energy utilities; and a proportional electoral system (though this last motion failed due to trade union opposition).

And yet, watching Keir Starmer’s 90-minute speech on the last day of conference, you wouldn’t know it. Only the Green New Deal was mentioned in the speech, and even then only in a watered-down form. Starmer’s top team flooded the airwaves to hurriedly pour cold water on members’ demands: shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves pledged to get “our public finances under control”, shadow home secretary Nick Thomas-Symonds ruled out a £15 minimum wage, and Starmer himself rejected nationalisation of energy companies. It seems that the leadership’s overriding message from the party conference was simply one phrase: “this is not the moment.”

Starmer’s supporters are confident that this policy-lite approach is in tune with the public mood. But with recent polling showing that Starmer is less popular than Jeremy Corbyn, the strategy doesn’t seem to be working. As Labour struggles in the polls, the very policies Starmer has repeatedly rejected remain hugely popular with voters. Maybe his members know something that he doesn’t?

Policy.

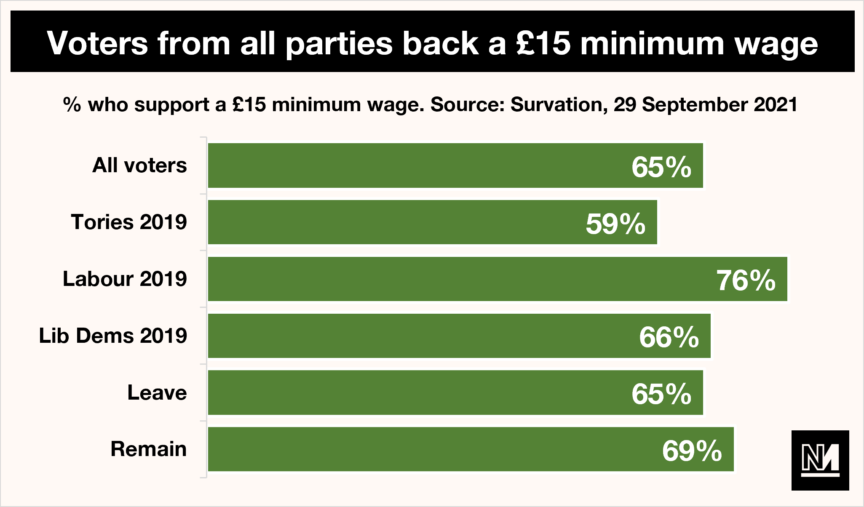

When it comes to specific policies that members backed, it certainly seems that members are more in touch with voters. For instance, despite Starmer rejecting the idea, a poll conducted on 29 September found that 65% of voters backed increasing the minimum wage to £15 over the next few years. This includes nearly 80% of Labour’s own voters. Even though the leadership opposes the idea, Labour members endorsed it during the party’s annual conference – putting them far more in tune with the electorate than the party leadership on this issue.

But it’s not just that members and voters agree on the issue of wages: it’s that party members, who endorsed a £15 minimum wage despite opposition from the leadership, are more in touch with the economic reality faced by the electorate.

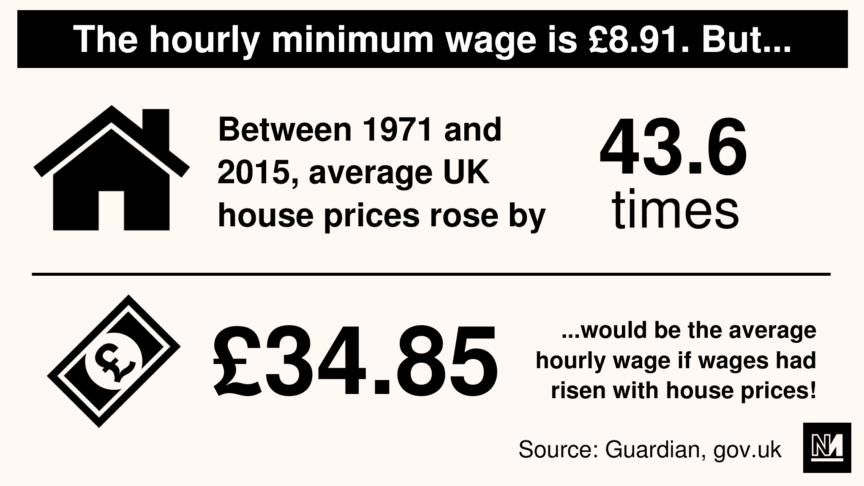

Take, for example, housing. Between 1971 and 2015, average house prices rose a stunning 43.6 times. Had wages risen in line with house prices, the average hourly wage would be £34.85 – compared to the current minimum hourly wage of £8.91.

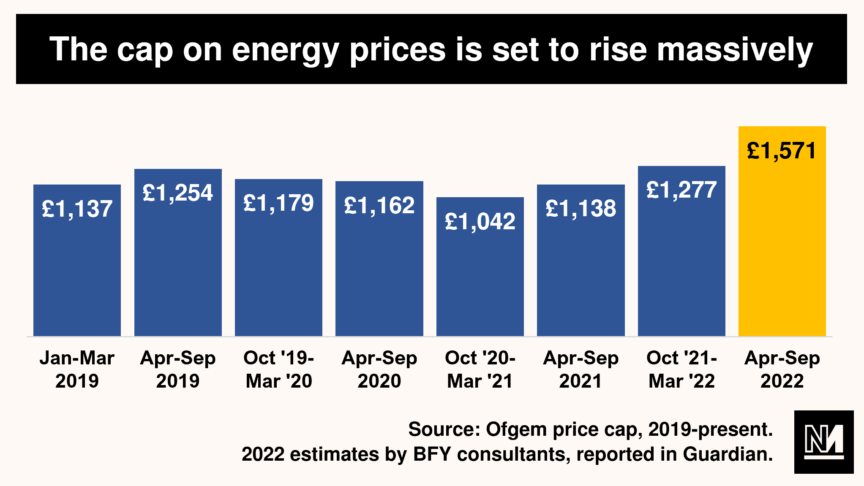

In this context, Starmer’s refusal to consider anything but a £10 minimum wage is laughably out of touch with the reality of how voters actually live. This is also true on the issue of energy nationalisation. Despite Rachel Reeves insisting that “this is not the moment” to bring energy companies into public ownership, most voters are getting a raw deal from the free market: it’s been estimated that by this time next year, annual energy bills will be an eye-watering £500 higher than they were in March 2021.

Given these massive price rises, it should be unsurprising that both voters and Labour members concur on nationalising energy companies. Polling from Opinium shows that 53% of voters would back the idea, with just 15% opposed. Yet Starmer has ruled it out. Once again, Labour members – who spend every day dealing with rising energy bills, like their fellow voters – are in touch with the electorate on this key issue, whilst the leadership is swimming against the tide of public opinion.

The final policy worth considering is proportional representation (PR). Though the proposal failed to pass at conference due to trade union opposition, 70% of constituency delegates cast a vote in support of the idea. Starmer, by contrast, did not express support for the idea; this was interpreted by some as a rejection of PR by the leader. Yet once again, members are in touch with the electorate – voters back PR by a margin of 44% to 15%, according to a recent SavantaComRes survey.

Priorities.

The leadership is also out of touch with voters in a more general sense, on which issues to prioritise. Starmer and Labour’s recent announcements make clear that the leadership’s focus is on reducing crime through higher police numbers, cutting taxes for businesses, appearing fiscally credible and stopping a leftwinger from ever becoming Labour leader.

But all the data suggests that voters are not particularly concerned about these things. Just 21% of voters think crime is one of the top issues facing Britain, with healthcare (48%), the economy (44%) and the environment (31%) all ranking far above it. Far from wanting tax cuts for businesses, 52% of voters think firms should pay more tax. And as for fiscal credibility? 65% of voters want higher taxes on the rich, 70% want more money spent on the NHS, and 59% view the furlough scheme as a success.

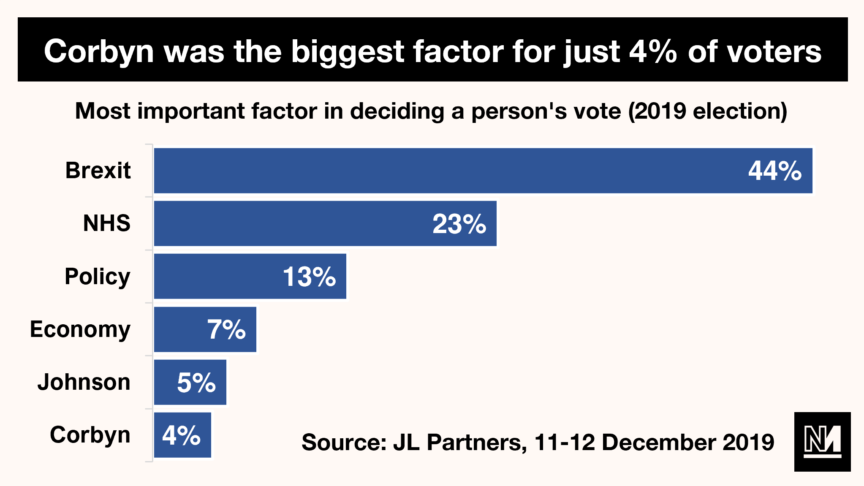

Finally, despite the leadership’s incessant focus on distancing themselves from Corbyn’s leadership, polling from 2019 shows that opposition to Corbyn was a concern for just 4% of voters – and polling in 2021 shows that more voters now approve of Corbyn than approve of Starmer himself.

None of this data suggests that the public is crying out for the Labour leadership’s priorities. Rather, the public mood has been captured far more accurately by Labour members’ priorities as expressed at conference: a Green New Deal to boost the economy and protect the environment, higher wages for workers and a publicly owned, well-funded health service.

But why are members so much more in touch with voters than the leadership? I would ascribe it to the fact that Starmer and his shadow cabinet are full-time politicians who spend most of their time in central London. Their days are filled by talking to Westminster insiders, socialising with Westminster insiders, debating the opinions of Westminster insiders, and reading columns written by Westminster insiders. They are far, far removed from the actual experiences of ordinary voters.

Labour members, by contrast, are ordinary voters – they work normal jobs, socialise with non-political people, volunteer for Labour alongside their other work and experience the same financial pressures that most people experience. They are far more in tune with what their communities and families need than the party leadership in Westminster.

In this context, the gulf between the leadership and the voters makes total sense. The received wisdom in Westminster is that Blair’s 1997 campaign was the peak of electability, and Starmer is now re-enacting it, right down to recycling the”tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime” slogan. This worked in 1997: for a variety of reasons, it caught the public mood. But it is not 1997 anymore, and if Labour wants to capture the public mood in 2021, it could do worse than to listen to its own members.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties and a columnist for Novara Media.