Disability Politics Are Anticapitalist Politics

The social model exposes the brutal way capital treats people who can't be exploited for profit.

by Ellen Clifford

18 November 2021

Listen to this article as audio:

A common complaint down generations of disabled campaigners is the perceived failure of the wider left to engage seriously with disability politics. This may seem unfair to those non-disabled allies who have actively fought Tory cuts or proactively taken steps to improve access and inclusion; there are even ground-breaking examples of non-disabled campaigners developing political education around disability. But it remains the case that disabled people make up 21% of the UK population and are the world’s largest minority – yet only relatively few people, almost exclusively disabled activists and academics, have taken a historical materialist analysis to the question of disabled people’s oppression.

It is a source of constant frustration that those who hold progressive ideas in all other areas, still tend to understand disability in line with the negative attitudes and prejudices common throughout wider society. There is a gulf between these prejudices and the understanding politicised disabled people have developed of their oppression. Levels of familiarity with disabled people’s own understanding of disability are immediately evident by the language people use. The instant that anyone in Britain uses the term “people with disabilities” instead of “disabled people”, they are marked out as either not knowing or, worse, refuting the social model of disability.

The social model of disability is the holy grail of disabled people’s politics in Britain. Traditional approaches to disability locate it as a deficit within an individual person, in effect blaming the person for the difficulties they experience in life. The social model turns this on its head.

The social model takes disability out of the person and locates it instead within capitalist society as a form of oppression. According to the social model, disability is created by structures that exclude and marginalise people whose differences either lead directly to or are associated with lower productivity in the workplace. From this flows attitudes that other disabled people, and regard our lives as worth less. The fact that disability continues to sit on the margins of society, generally regarded as a special case relevant to only a few, is testament to the dominance of ideas that serve the interests of the ruling class.

Disabled people often describe it as a light bulb moment when we first discover the social model. After years of internalising negative ideas about our human value, we suddenly realise that we are not the problem – the problem is society, and it is society that needs to change. It is an intensely liberatory concept that translates easily. As a tool for achieving social change it is also extremely effective, transforming disability from a matter of personal tragedy into an issue that is both deeply political and of collective importance.

The social model powerfully exposes the brutality of capitalism in its treatment of members of the working class who are unable to be exploited for profit. It is therefore disappointing that there is little interest in it beyond the disabled people’s movement.

Disabled by what?

Perhaps people have heard the term the social model and think they understand it; perhaps they assume it simply means that there are socio-economic causes of disability. But it is so much more than that. Impairments and illnesses are caused by capitalism through imperialist wars, poverty, poor working conditions and damage to the environment – but they also exist independent of socio-economic circumstance. Disability is not a form of oppression that can be overcome just by removing stigma; inclusion of disabled people requires dedicated investment, fundamental changes to normative standards as well as to the structures and systems embedded within mainstream society.

The social model draws a distinction between “impairment” and “disability”. Here, “impairment” refers to the physical, mental or cognitive conditions that disabled people live with, while “disability” is the level of oppression that society imposes on us on top of our impairments. This is why we use the term “disabled people”, because we are disabled by society.

There is no denying the very real pain and distress that many disabled people experience. The exact nature of this will depend upon the particular condition the individual has and even then, it can change from person to person. The term “disabled people” encompasses a huge spectrum, from people with mobility impairments to autistic people to people living with mental distress to people with energy limiting chronic illness or other health conditions.

What unites us are our experiences of oppression such as barriers to employment and education, prejudice and poverty. There is an intrinsic relationship between disability and poverty, where poverty is both cause and consequence of disability. Disabled people in Britain are now at least three times more likely to live in severe material deprivation than non-disabled people. Moreover, poverty levels are one of the factors named by the office for national statistics as contributing to the way that disabled people died disproportionately from Covid-19 even after accounting for health and age-related factors.

The dominant idea in society – that disabled people are inevitably excluded, without the same life chances as other people, because we have something wrong with us – is socially created. The category of disability did not exist until the rise of capitalism. People with impairment or illness fared differently depending on their individual condition and its intersection with socio-economic factors. It was the standardisation of labour that resulted in the creation of a category for those unable to fit productively in the workplace. As Roddy Slorach tells us in his book A Very Capitalist Condition: a History and Politics of Disability, the word “normal” referred to nothing more than a right-angle carpenters’ square before the industrial revolution.

Working-class solidarity.

The cost of supporting people who may never labour productively in the workplace is one that capital will always resent and do its utmost to minimise. At times of recession, it is a cost that will be in the firing line, as disabled people in Britain directly experienced under austerity.

Views of disability that locate it as a problem within an individual successfully disguise both its wider relevance and its deeply political nature. The question of what happens to a person who is unable to earn their own living through employment is of significance to the entire working class. When this is recognised, it can lead to powerful displays of solidarity. This is one reason why Hitler had to officially end Aktion T4, the Nazi programme that mass murdered disabled German citizens – knowing that old age, industrial accident or being wounded on the frontline would lead to a swift extermination had become a concern for the German populace.

One of the most notable protests that happened against Nazi rule occurred in a place named Absberg when the grey Aktion T4 buses turned up for the residents of the local disability institution. The residents were regarded as part of the community and their neighbours did not want them killed. Tragically, they were not able to save them, but concerned reports filed by local Nazi party officials reveal the pressure that grassroots opposition achieved. Although individual killings of disabled people by their physicians continued until after the Allies invasion of Germany, Hitler ordered the suspension of the T4 killings on 24 August 1941.

The changing nature of work.

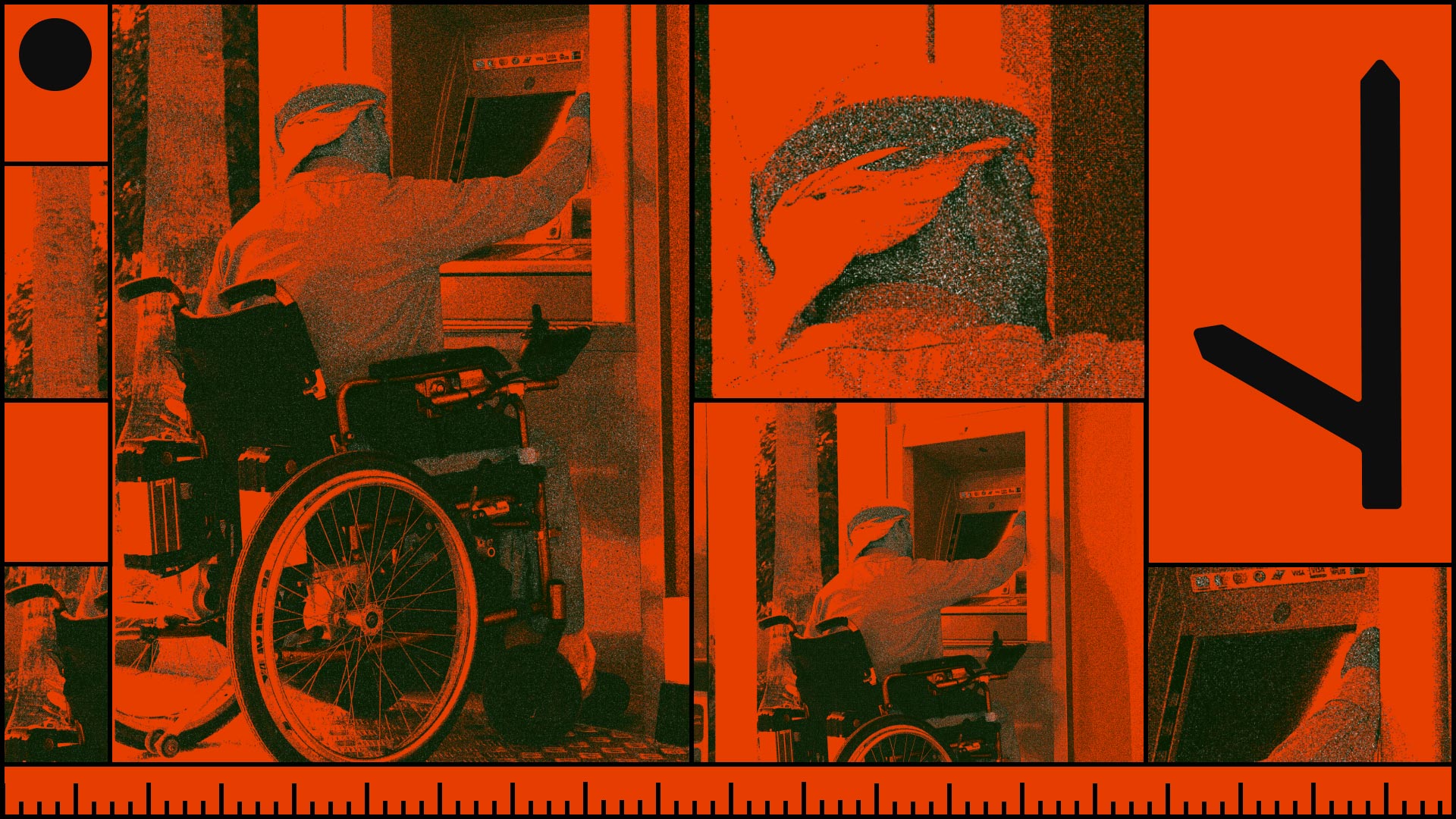

The individual model of disability dominant within capitalist society also obscures the fact that disability is not static. Disablement is classified according to the possession of an “impairment” that limits one’s ability to function in day-to-day life. The impact of an impairment on a person’s ability to function is subject to socio-economic factors and can therefore change. For example, the wide availability of glasses in Britain means that many people with limited vision are not disabled by sight loss.

Research has shown that disabled people were less likely to be in employment in Britain after we moved from an economy dominated by manual industry to the customer service sector. This has corresponded with a rise in the reported prevalence of disability and additional spending on disability benefits. A traditional argument of the left is that Thatcher pushed people on to incapacity benefit in order to manipulate the unemployment statistics. A more pressing issue in the here and now is that employment has been shown to mask disability (or “incapacity”). The modern workplace is moving rapidly towards greater insecurity, greater standardisation, greater stress, longer hours and lower control for workers at the same time as lowering the burden of responsibility on employers to protect workers’ rights and provide benefits such as sick pay. It is no wonder that disability prevalence is rising as growing numbers of people find themselves unable to compete within prevailing labour market conditions. The reasons why individuals are unable to compete then become identified as disability.

It is somewhat ironic that Conservative politicians often seem to understand disability better than the left. Under a capitalist economy, there are very real contradictions between demands for equality and the way that labour is valued. These frequently erupt into protests when every so often a Tory minister will suggest that people with learning difficulties should be paid below the minimum wage. Their argument is that this would benefit the thousands of people with learning difficulties wanting to work but currently excluded from employment due to lower productivity rates. The only ways around this issue, whether forcing employers to take on disabled workers, subsidising disabled people’s employment or creating exceptions for the payment of lower wages, all come into direct conflict with values of equality. The truth is that following the intensification of labour over recent decades, there is now an impossible circle to be squared in order to equally value and respect disabled people within a labour market driven by the pursuit of profit.

All people are interdependent.

Respect and dignity are earned through hard work. This is drummed into popular consciousness through political rhetoric and the media. It is also why so many disabled people who can’t find employment are so desperate to work. Alongside popular ideas about human worth there also exists a deep human instinct to support each other and to share resources with those who cannot survive on their own. This contradicts the narrative of individualism that upholds capitalism; the myth of our essentially selfish nature encourages competition that divides the working class and prevents us from realising the strength of our shared interests.

All people are interdependent but, as Mike Oliver – the disabled researcher often described as the godfather of the social model – points out, disabled people are dependent to a greater degree than others. We exist of necessity within social networks that are more strongly interdependent. This gives us a unique perspective on society, as does the oppression that casts us as outsiders looking in on the rest of society and its dysfunctionality. Additionally, some forms of neurodivergence actually lead to a greater ability to identify and a greater motivation to challenge social injustice.

The question of disability sits at the heart of the struggle between the few and the many; it represents the cruelty of capitalism in its disregard for the lives it casts aside in its pursuit of profit, justified by its individualistic model of disability that blames us for our own disadvantage under a deeply unequal and unfair system. The precarity of the lives of the many under such a system is neatly embodied in the fact that anyone can become disabled and thus be thrust into the situation of having to prove your worthiness of support to survive.

But this isn’t a moral question. And disabled people don’t want you to care about us because you think you should. We want more people to start questioning the ideas about disability they have grown up with and to understand the importance of disability within anticapitalist struggle. Understanding disability involves interrogating the very fabric of capitalism. It also helps us to understand that an alternative is possible. One where we are not confined by the pursuit of profit and where interdependent social structures allow us the freedom to fulfil our personal potential. Winning such a society cannot be achieved by any single group; it requires collective action. It’s a journey we need to take together.

Ellen Clifford is a disabled activist and author of The War on Disabled People: Capitalism, Welfare and the Making of a Human Catastrophe.

This article is part of a focus on disability. Read more here.