Our Toxic Work Culture Isn’t Just Harming Disabled People – It’s Harming Everyone

We should be fighting for liberation from work, not just access to it.

by Sophie K Rosa

18 November 2021

Listen to this article as audio:

When she was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) in 2015, Louise* was “working constantly” and “constantly thinking about [her] work” at the tech company that employed her.

Having felt “constantly sick” for a long time – all the while being too consumed by her job to seek medical attention – Louise finally made an appointment with a doctor, which led to her diagnosis. She now sees the toxic work culture she was subjected to – the long hours, constantly being on-call, checking her phone on holiday – as having both contributed to and exacerbated her condition.

The relationship between disability and work is complex; many jobs and workplaces are exclusionary and inaccessible, and yet disabled people are put under pressure by the state to seek employment, rather than rely upon the woefully inadequate benefits system. Disabled people, who cannot, or do not, want to work because of their health, often face discrimination, derided by both the government and the press as so-called benefit scroungers or fakers.

“Attitudes to work under capitalism are absolutely core to the way that people with impairments are disabled by society,” says Steve Graby, a disability researcher at the University of Leeds. When paid work is seen as “definitional of ‘adult’ and ‘citizen’ status,” he explains, exclusion from it is one form of oppression that creates disability. He notes that, traditionally, the disabled people’s movement has fought to remove barriers to employment, but emphasises that this approach cannot be the end goal: some people will remain excluded – “liberation from work”, not “access to [it]”, must be the horizon.

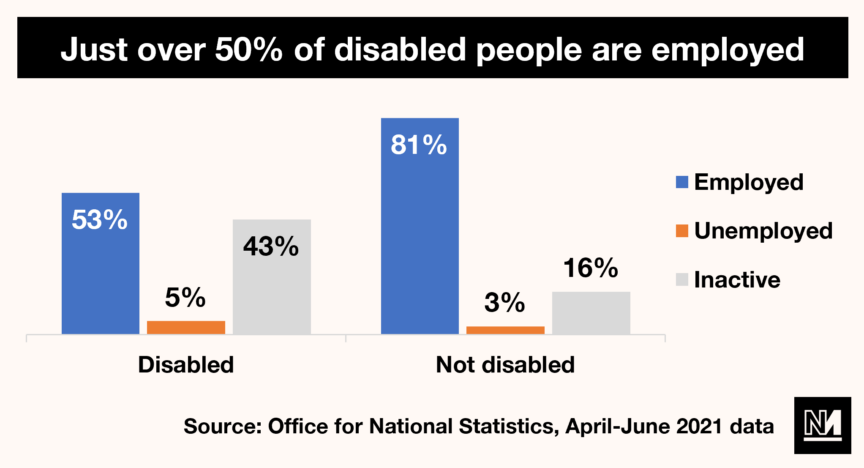

While this should no doubt be our overarching ambition, in society as it currently stands, removing barriers to paid employment remains a vital aim. The disability unemployment gap is currently at 28.6%, in large part due to inaccessible working conditions and workplaces. The government’s access to work scheme offers discretionary grants to support disabled people to take up or remain in work, but campaigners say the scheme itself is often difficult to access.

Five years ago, Becca Jiggens, an academic and disability employment lawyer, set up Just Reasonable Limited, a nonprofit law firm aiming to challenge disableism in the workplace. She argues there is a “pervasive narrative of disability faking”, obstructing people from receiving reasonable adjustments for their wellbeing. “The goodwill of a manager [is] pretty essential for disabled inclusion in the workplace,” she explains.

Initially, Louise didn’t tell her current employers about her MS when they hired her to work part-time in their clothing shop; when she eventually did, they questioned the seriousness and even existence of her impairment. To help combat their ignorance, Louise printed out some informational booklets, but one manager told her she wouldn’t read them, and instead handed her a book about a diet that claimed to “cure any illness”.

What’s more, during the pandemic, Louise’s bosses asked her to work more hours – a request she declined, knowing that it would put her health at risk. Rather than accepting this, she says, they began to claim she “wasn’t dedicated to the business” and harassed her on a daily basis – with “constant nitpicking” and “screaming down the phone” – both during and outside of her working hours.

This “very high-stress environment” caused a decline in Louise’s mental health and an MS relapse that led her to have to sign herself off work in April. Following this, her bosses began periodically withholding her pay and sending “almost daily” communications asking her when she would be returning to work. “My relapse has continued,” explains Louise, “mostly because I’m so stressed about returning to work”.

Exclusion is the other side of the coin to exploitation.

This kind of experience, says Jiggens, reflects our culture of work in general; it is one that frames workplace discrimination as the worker “not trying hard enough,” and the inability to work as a “moral failing” or a “character flaw”. Working hard and earning money, she says, is culturally linked to “an individual’s inherent value” – a principle that harms everyone, but especially disabled people. Graby agrees: “Exclusion is the other side of the coin to exploitation – those who cannot be profitably exploited are seen as ‘useless,’ and a huge ideological apparatus rests on this.”

Reflecting on her time working at tech company Blizzard Entertainment before her diagnosis, Louise says the “very high pressure” workplace culture was encouraged by “core values” such as “work hard, play hard” and the gently manipulative idea that “we’re a family”. The company has a blue logo and “one of the catchphrases,” Louise recalls, was “I bleed Blizzard blue”.

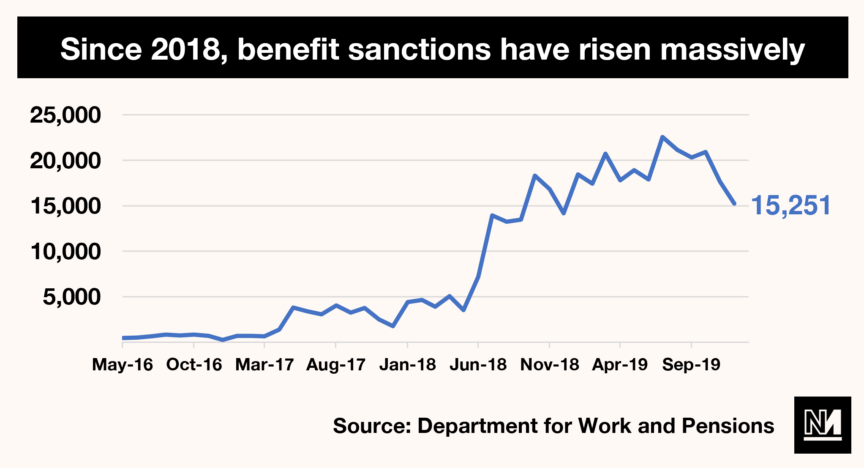

Under capitalism, work is considered central to our very existence – and disabled people’s struggle is not only against exploitative workplaces but against the obligation to work at all. Through punitive benefits regimes and oppressive assessment processes, the state often forces people into work; whilst not in work, social security often leaves people struggling to survive.

Louise says the idea that “if you’re on unemployment benefits, you’re just a slacker,” has been “shoved down” her throat. As a result, she says, she feels compelled to stay in work that’s making her physically ill.

Considering the relevance of antiwork politics to the disabled people’s movement, Jiggens says: “Integration into an imperfect system is a means to an end, it’s never going to be an end unto itself.” What’s more important, she says, “is to move away from work being the essential defining feature of our society.”

What can we do to create flourishing?

Graby says the left as a whole needs to rethink its attitude to work and its relationship to disability. Referring to the Labour party, he points to how “work ideology” is “right there in their name”. “The idea of working-class pride” can diminish the fact that work itself is “an inherently exclusionary and exploitative system,” he says.

Indeed, labour movements have much to learn from disabled people’s struggles. Graby notes that resisting the “divide-and-conquer” tactic that is imbued in the ideology of work – of the moral employed versus the immoral ‘scroungers’ – is critical to the disabled people’s movement. And it must be to the broader labour movement too. “Solidarity between exploited and excluded sections of the working class” is vital, he says, adding that if any group of people are to be seen as “parasites”, it should be the ruling class.

The Boycott Workfare campaign, opposing ‘workfare’ policies in the UK – in which unpaid work was forced upon people receiving benefits – is one such example of working-class solidarity transcending these divide-and-conquer tactics. Through campaigning and direct action beginning in 2010, the group had forced the government to scrap a number of workfare schemes by 2016.

In the immediate fight for a post-work society, Jiggens believes that holding bosses to account for discrimination against disabled people, as well as broader reforms such as the four-day week, are critical battlegrounds. The pandemic has highlighted how “capitalism not only creates disability but then neglects it and then frames it as a personal failing,” she says. As a result, “the structures, and those who profit from creating disability, take no responsibility for it.”

Whether the reason for struggle is disabled people’s liberation or something else, she says, “the issue is exactly the same: what can we do to create flourishing, to enhance everybody’s experience of being alive for a short period of time?”

*Louise’s name has been changed to protect her anonymity.

Sophie K Rosa is a freelance journalist. In addition to Novara Media, she writes for the Guardian, VICE, Open Democracy, CNN, Al Jazeera and Buzzfeed.

This article is part of a focus on disability. Read more here.