Deaf People Are Paying Thousands to Learn Their Own Language

Listen to this article as audio:

Cop26 was an accessibility nightmare. For two weeks straight, the UK government made it clear how little thought it gives to Deaf and disabled people. After waiting outside for two hours, an Israeli minister and wheelchair user was forced to give up trying to access the climate summit and returned to her hotel. Meanwhile, despite a judge ruling that the Cabinet Office had breached equality law by failing to provide a British Sign Language (BSL) interpreter for its Covid-19 data briefings, all but one of Boris Johnson’s press conferences in Glasgow were delivered without one visible.

This episode is but the latest in the government’s long and varied history of failing disabled people, and Deaf people specifically. Audism (that is, prejudice towards and discrimination against Deaf people) is ingrained in our society. Public services are still heavily reliant on telephone/auditory communication, in a way that makes information about train disruptions during a visit to London impossible for me to understand. In the arts, cinemas are completely inaccessible to us, with subtitled screenings at 1pm on a Monday implying that Deaf people don’t work.

Education is a key arena of audism in British society. This dates at least to the 1981 Education Act, which prioritised educating children with special educational needs in mainstream schools rather than in specialist establishments. The aftershocks of such legislation are still felt today.

Last year, the Consortium for Research into Deaf Education found that one in 10 teaching assistants for Deaf children and 7% of communication support workers had been cut from England’s schools since 2018. This year, Deaf pupils fell an entire GCSE grade behind their hearing peers for the sixth year running. Things hardly improve when Deaf people enter employment. In 2017, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) found that Deaf people are twice as likely to be unemployed as hearing people. while research by the National Deaf Children’s Society last year revealed that two-thirds of Deaf young people would hide their deafness on a job application.

Meanwhile, more and more spaces where Deaf people would gather and connect are closing. While the Deaf community continues to have a strong presence on social media platforms, few Deaf clubs and opportunities for Deaf people to congregate in person remain.

The impact of this is significant. When Walsall Deaf People’s Centre closed in May 2019, the local community mourned the loss of a “lifeline”. Robert G Lee, a senior lecturer in BSL and Deaf Studies at the University of Central Lancashire, told British Deaf News in 2018: “What you saw at the Deaf club was everybody from babies up to people in their 90s, a whole range of Deaf people. I learned to communicate with people of different ages and genders, whereas now people tend to hang out with those of a similar age to them.

“People don’t get to see the range of community that the Deaf clubs offered, that was my experience,” he said.

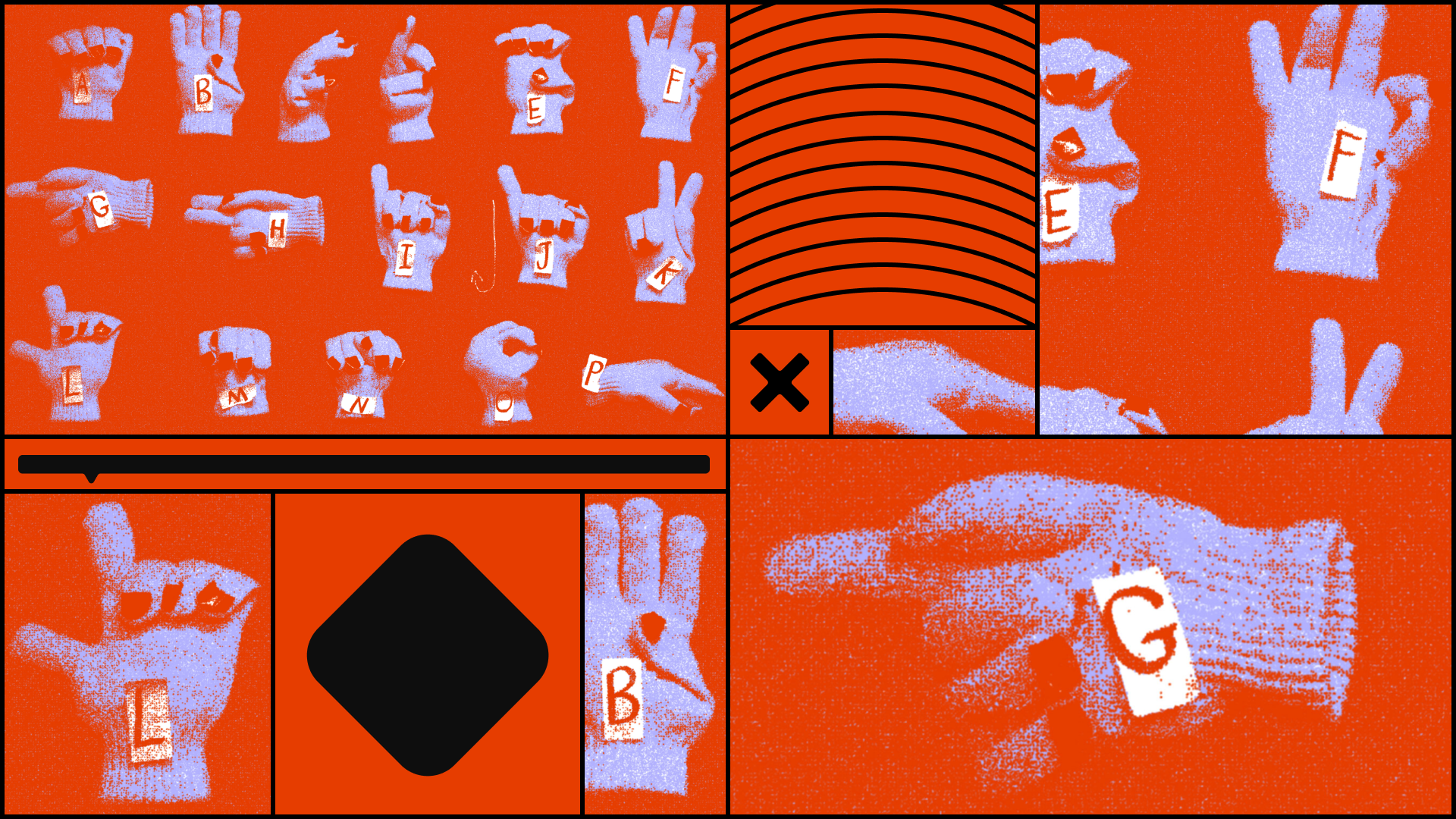

As Britain’s Deaf community continues to be marginalised, it falls to language – in our case, British Sign Language – to keep us together. Yet even this is under attack.

This became apparent to me back in 2014, when I took my first steps in the Deaf community. Hailing from a small area in Bedfordshire, I didn’t know of many other deaf people locally. It was through a national charity’s youth board that I met other Deaf people from across the UK, and I started to learn BSL from other members.

While I’m of the view that BSL isn’t a mandatory part of being in the Deaf community, I owe a lot of the opportunities which have come my way in the past seven years, and the connections I’ve made, to knowing a fair amount of sign language.

It is therefore shameful that students who communicate in BSL are still waiting for a GCSE in their first language; the Department for Education continues to drag its feet over something it first promised in 2018, after Deaf schoolboy Daniel Jillings threatened legal action.

I wish I could learn more of the language myself, but accredited courses cost hundreds, even thousands of pounds. It’s one thing that hearing people can’t learn sign language and so break down a communication barrier between the hearing and Deaf. It’s another when Deaf people can’t even access their own language.

To avoid a dangerous class divide within an already marginalised subculture, we must move away from a society in which language is paywalled. The government must adequately fund educational support for deaf children, and accelerate work on a British Sign Language (BSL) GCSE which can open up the language to so many more people.

It also has an opportunity with Labour MP Rosie Cooper’s BSL bill, which looks to make BSL an official language of the United Kingdom (it was recognised by the government in 2003, but this did not grant it legal status), set up a BSL Council to advise on the language, and “establish principles for the use of BSL in public services”.

Despite being supported by the British Deaf Association (BDA), alongside eight other organisations representing Deaf people, it’s unclear whether the Conservatives will back the bill. In 2015, then-minister for disabled people Justin Tomlinson said the government had “no appetite” to grant legal status to BSL, and there’s little evidence available to suggest that the Tories have shifted their stance since.

Yet the impact of a BSL Act would be huge, not just giving BSL the status it deserves, but cohering the Deaf community and enabling us to participate fully in wider society.

It’s time for the government to finally make good its promise to introduce a BSL GCSE and throw its support behind a BSL Bill when it has its second reading in January.

Liam O’Dell is an award-winning disabled freelance journalist and campaigner.