Poor Brits Live Much Shorter Lives. What Can We Do?

A better-funded NHS is only part of the solution.

by Ell Folan

20 January 2022

In 2020, life expectancy in England fell more dramatically than at any other point since WW2, as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. While the coronavirus shockwave hit everyone, some were more affected than others.

In poorer areas, life expectancy declined by nearly twice as much as it did in wealthier ones; BAME people died from Covid-19 at much higher rates than white people; while people with disabilities faced a significantly higher death rate than able-bodied people. The pandemic also exposed regional health inequalities: the northwest experienced a far higher proportion of deaths from Covid-19 than the southwest, for instance.

Far from creating these healthcare inequalities, the pandemic simply laid them bare. Both regional and economic inequalities have been producing significant disparities in health and life expectancy rates for decades. While some of these inequalities are the result of long-running, structural factors, which will take time to unravel, many can be alleviated by implementing ambitious, socially transformative policies.

There’s a link between deprivation and life expectancy.

When it comes to health inequality, Covid-19 represents the tip of the spear. Even prior to 2020, there were significant disparities in life expectancy between different social and regional groups. Some of these variations existed within tight geographic spaces; average life expectancy in the London borough of Westminster, for instance, was 86.1 years in 2019. Yet just one borough over, in Islington, the average was 81.5 years.

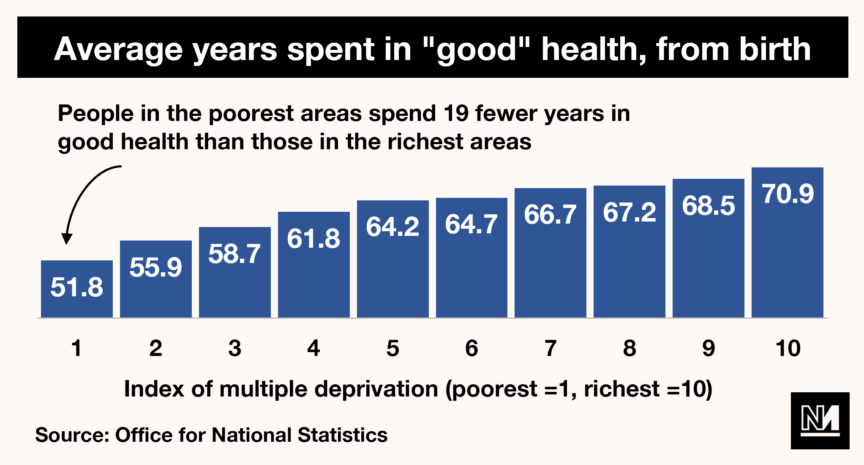

Overall, the most deprived areas recorded a far shorter life expectancy (74.1 years) than the least deprived (83.5 years). That gap in itself is notable, but not enormous. However, when you measure healthy life expectancy (i.e. how long someone is likely to live in “good health”) the difference is genuinely jaw-dropping: in the poorest areas, people live just 52 years in good health, versus 71 years for those in richer areas.

But life expectancy is not the only health inequality in Britain. There is also a massive difference in rates of mental illness across social groups: LGBT+ people report higher rates of depression and anxiety, and 80% of homeless individuals experience mental health problems.

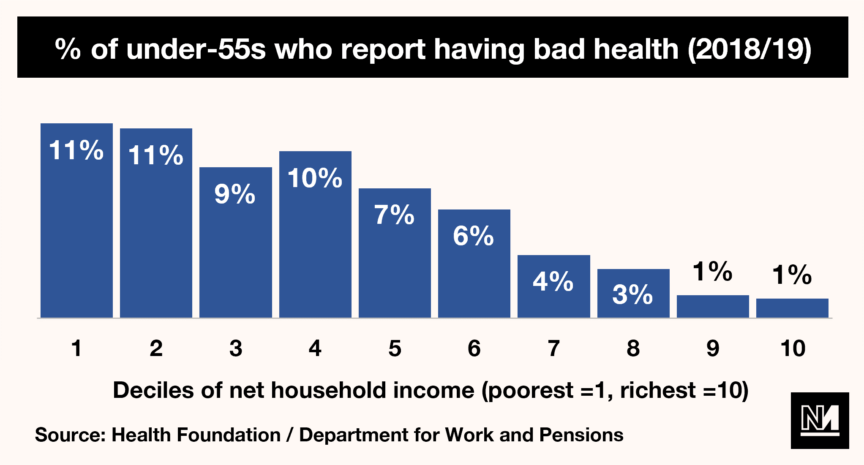

Poverty, unsurprisingly, also has a large role to play in affecting the health of Brits. As the Health Foundation has outlined, poor health is much more common amongst the poorest 10% of people in the UK than it is amongst the richest 10%. And with Covid-19 devastating the economy, plunging even more people into that bottom 10%, this inequality will only have worsened.

Correlation, of course, is not proof of causation. It is therefore important to establish the source of these health inequalities. As a starting point, when pondering the question of why poorer Brits are living shorter lives, the intuitive answer would be lack of money – and that is broadly accurate. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has argued that living on a lower income limits a person’s access to health-improving goods like gyms, is more likely to lead to unhealthy behaviours like smoking and causes both stress and low self-worth (both of which tend to affect health).

But health is also impacted by income in more indirect ways. Lack of income often results in people living in cold, poor-quality housing filled with damp and mould, which can lead to higher rates of cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and mental illness. What’s more, people living in deprived areas have less access to green spaces, giving them fewer opportunities for both exercise and for the well-documented mental health benefits of green spaces.

All of these factors – increased chance of disease, fewer opportunities for health improvements, higher rates of unhealthy behaviours – are highly likely to cut the life expectancy of the poorest Brits. And all can be traced, directly or otherwise, to having a lower income.

We must take a more holistic approach to health.

Having outlined the problems and their causes, the next question that naturally flows from this is: what can we do to fix these problems? One simple answer is to give our health service the resources it needs to provide everyone who uses it with a high standard of care: under New Labour, NHS funding rose significantly, with life expectancy in the poorest areas of the country rose at a higher rate than in the richest areas.

That said, better funding is only part of a much more complicated solution; even after 13 years of New Labour in power, there were still huge disparities between demographics and regions. Male life expectancy in 2010-12, for instance, was 77.7 years in North West England and 80.3 years in the South East. Simply funding the NHS better, therefore, is insufficient in solving healthcare inequalities.

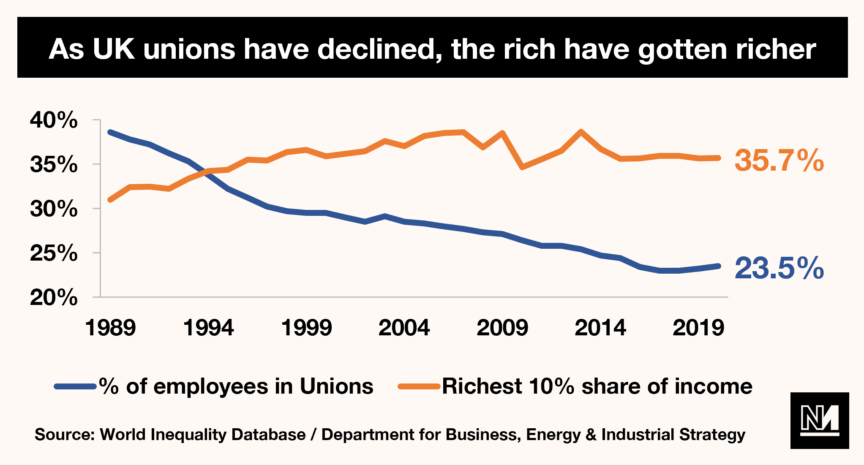

Rather, as a society, we need instead to take a more holistic approach to health. As discussed above, low income and poor housing are two of the most significant drivers of poor health in Britain. The government’s priority should thus be to increase wages, both by increasing the minimum wage and strengthening trade unions so they can fight for better pay. The latter is particularly significant, as the declining power of trade unions in Britain has been accompanied by a stunning rise in income inequality.

At the same time, the government must take action to increase the supply of decent housing by undertaking a programme of building affordable council housing. As a result of Thatcher’s Right to Buy policy, at least 1.6m council houses have been sold off since the 1980s. This, combined with a lacklustre house-building programme by successive governments, meant that by 2013, just 8% of Brits lived in council housing – down from 42% in 1979. This matters because council houses tend to have big rooms, lots of storage and separate kitchens. As the Evening Standard put it: “Council homes were originally built for living and not for profit.” These superior conditions will directly affect the health of residents.

To build a healthier, happier and more equal society we must do more than simply increase NHS funding. It is vital that we embed into policy a genuine commitment to a truly universal healthcare service, build an economy in which workers are powerful and well-compensated and ensure that we all have decent, secure housing.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties.