The Met Just Apologised After Strip-Searching Me. I Don’t Believe a Word of It

The police’s dismay is performative – they knew exactly what they were doing.

by Koshka Duff

24 January 2022

Content note: The following article contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault.

Imagine you are surrounded by an armed gang. They tie your hands and legs together, pin you to the ground, and cut off your clothes with scissors. While grabbing you all over, ripping out your earrings and hitting your head off the concrete floor, they crack jokes about the benefits of strapless bras. They call you childish for objecting.

That was my experience of being strip-searched at Stoke Newington police station.

It was May 2013 and I had been arrested for offering a legal advice card to a 15-year-old who was being stopped and searched.

That made me a “bleeding-heart lefty” and “some sort of socialist” and a “very silly girl”, according to the sergeant who took me in. The fact that I then engaged in passive resistance and wouldn’t give the police my details meant some softening up was in order – hence the strip search.

CCTV footage of the incident, released to my lawyers last year and published today in the Guardian, offers a peephole into the police psyche.

“Bend her arm mate, tell them to put their back into it … do I have to come down there and do it?”, custody sergeant Kurtis Howard, who ordered my strip search, is heard complaining over the intercom. “By any means necessary, treat her like a terrorist, I don’t care.”

Footage from immediately after the search shows men and women officers cracking jokes about what body hair they found (“a lot”) and whether my body was “rank” (surprisingly not, as it turns out).

In October 2021, I received £6,000 in compensation and an apology from the Met. I don’t believe a word of it.

Just doing their jobs.

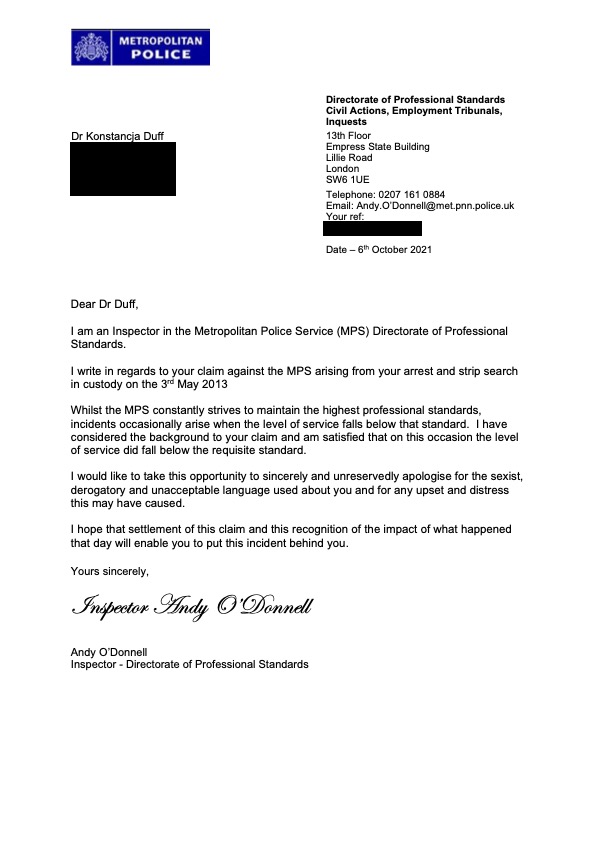

The police’s sudden decision to apologise “sincerely and unreservedly” for the “sexist, derogatory and unacceptable language used” by the officers who strip-searched me (albeit not for the strip-search itself) was an interesting departure from the line they had maintained for eight years.

Throughout that time, they had insisted that how they treated me was totally normal, business-as-usual, just doing their jobs. Meanwhile, both sides racked up tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of pounds in lawyers’ and court fees (which I was only able to pay through crowdfunding and a conditional fee agreement with my lawyers).

The Met was backed to the hilt by the police complaints system. At a “public hearing” for gross misconduct in 2018 – no members of the public were allowed into the room – a supposedly independent panel dismissed the case against Howard without even questioning him.

“To the extent that the incident was traumatic for the Claimant,” pronounced the police’s solicitor with Dickensian flourish just last year, “[she] has been the author of her own misfortune.”

Their apparent change of heart must be credited, at least in part, to a political climate transformed through struggle: the steady stream of revelations of misogyny in policing following the rape and murder of Sarah Everard by PC Wayne Couzens; public awareness generated by the Black Lives Matter movement; and campaigns like #SayHerName. However, we should not be too quick to take admissions of wrongdoing as a sign that the police’s institutional sexism will be seriously addressed.

To date, no officer in my case has been disciplined. Far less has any change been made to the routine use of strip-search powers to punish and intimidate members of the public, particularly young people of colour. Nor to the occupation-style policing of Black, Brown and working-class communities and escalating repression of dissent, in the context of which these powers are deployed.

The police’s crocodile dismay at how such an “unacceptable” incident could have occurred was damage control, a strategy for deflecting public scrutiny. By presenting themselves as shocked, they present the incident as exceptional.

This disguises the key fact that misogyny and sexual violence are normalised within policing. For eight years, the officers who assaulted me claimed that they were just doing their jobs, and the entire complaints system backed them up. Perhaps we should take them at their word.

Discredit and disappear.

Following the incident in 2013, I was slapped with several spurious charges of obstructing and assaulting police – a well-tested police procedure for discrediting people they have abused by painting them as “violent” and “criminal”.

Decisive in the trial, at which I was acquitted, were photographs of my injuries, which my legal representative had taken while I was still in custody. On the stand, the officers couldn’t say where the injuries came from.

“When people come in contact with police, they just start hurting themselves,” was one explanation, delivered with the swaggering authority of one accustomed to being believed. (Another of this officer’s professional opinions: “If someone’s not complying, not giving their details, they’ve either got learning difficulties or something to hide.”)

Sound legal advice is a luxury most people targeted by police do not have. Duty solicitors cannot be trusted not to be in cahoots with their colleagues at the station, and pressure to accept cautions or plead guilty without trial is immense.

Then, if the criminal legal system hasn’t disappeared you into prison, the civil legal system is set up to disappear your complaint into a bureaucratic abyss.

The costs of a civil action against the police are prohibitive. In my case, the insurance payments alone required a crowdfund to raise £7,560. We’d have needed a further £11,424 to take it to trial.

Legal aid is paltry and unavailable to most. The application procedure is so complicated that trained lawyers struggle to fill in the forms.

In this context, police solicitors and bodies like the Independent Office of Police Conduct can simply ignore what are on paper their legal duties (for instance, to provide CCTV footage, or to question the officers involved) for months or years on end.

Cases like mine, which through some combination of luck, privilege, and improbable perseverance get past this barrage of discredit-and-disappear tactics to a (semi-)sympathetic public hearing, are exceptional only in that anyone has ever heard of them.

At this point, they turn on the dismay. “Sorry, we made a shocking mistake when we did this (read: to a person like you).” And just like that, faith in the system is restored.

Movements against police sexism and misogyny must be alert to this ideological manoeuvre or risk being split along lines of ideal victimhood that are classist, racist and ableist.

A bad barrel.

The manoeuvre I have described is evident in the wording of their apology. “Whilst the MPS [Metropolitan Police Service] constantly strives to maintain the highest professional standards, incidents occasionally arise when the level of service falls below that standard,” writes the inspector in charge of my complaint. “I have considered the background to your claim and am satisfied that on this occasion the level of service did fall below the requisite standard [my emphasis].”

Beyond the stale “bad apples” line, there is something almost hilarious about your sexual assault being apologised for as if it was a takeaway pizza that arrived cold.

But the language of service and care plays an important role in masking the violent realities of policing.

The justification accepted by the misconduct panel for my strip-search was that I “might have had mental health problems,” essentially offering carte blanche to forcibly strip anyone suspected of having a mental illness or disability – all for our own good.

The absurdity of this will be familiar to anyone who has seen police “medics” at a protest, in full riot gear, bellowing “Get back!” as they bash you with their healing sticks.

The apology’s focus on “language used” is also telling. What caused harm, after all, is not primarily what they said, but what they did.

That is not to say that words don’t matter. The police’s words, both during the incident and in their apology for it, reveal their attitudes and the culture through which these attitudes are reproduced in every new recruit.

This is embarrassing for the police because it undermines their cultivated public image of “professionalism”.

But realistically, these might be just the attitudes and the culture the police need to do what they do. A dehumanising mindset makes it possible to treat people like pieces of meat on a day-to-day basis – which is what they are tasked with.

In the 1950s, social scientists at the University of Berkeley, California, working with the critical theorist Theodor Adorno, identified a set of character traits associated with support for authoritarianism – what they called “the authoritarian personality”.

Characteristics included “preoccupation with the dominance-submission, strong-weak, leader-follower dimension, identification with the power-figures”; “disposition to think in rigid categories”; “disposition to believe that wild and dangerous things go on in the world”; “opposition to […] the imaginative, the tender-minded’; and “exaggerated concern with sexual ‘goings on’”.

Sound familiar?

Simply to pathologise such people, however, is an error that Adorno cautions against. The real problem is not that these traits are “inappropriate” – it is that they are all too appropriate.

Individuals with authoritarian personality types (now more commonly referred to as a “high social dominance orientation”) seem to be overrepresented in the police. Far from being maladaptive, such traits help people play their allotted roles in violent, hierarchical institutions, and in the deadening and crisis-ridden “order” these institutions enforce. That is why, Adorno argues, if we want a world in which these traits are not systematically inculcated and incentivised, it’s “the total structure of our society” we need to change.

One of the boys.

That said, the CCTV footage certainly views like an authoritarian personality bingo game at times. There’s the Jimmy Saville joke; the pseudo-edgy chat about dogging and cottaging; the officer intrigued by the thought of scraping up roadkill with a special roadkill scraper.

A point made by anticolonial philosopher and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon comes to mind: agents of oppression (soldiers, police, border guards) are themselves dehumanised by the dehumanising violence they inflict on others.

Watching Plod bragging about the size of his dick, followed by a graphic reenactment of a former partner struggling to contain his manly fluid (“had to [spit] … swallowed the first one… filled her up again! … and I was like yesssss”), it is easy to form the impression that misogyny in policing is quite straightforward, really. A bunch of guys with dangerously fragile masculinities, given some big ol’ weapons and the impunity to match, go on – unsurprisingly – to enact an authoritarian wet dream.

But folded into this too easy narrative is an assumption of feminine innocence and a reduction of patriarchal institutions to men and their dicks – an assumption we need to resist.

Often the first thing people want to know is whether it was men who strip-searched me. When I tell them it was women (although with men at the open door), responses vary between relief (“Oh, it wasn’t that bad then!”) and disappointment (“Not as spicy as I’d hoped!”). Yet the image of women as necessarily softer, more caring and less invested in practices of sexualised humiliation is itself a sexist nonsense.

In my experience, female officers can be cruel and vindictive with the best of them. They throw misogynist insults and impose the diktats of normative femininity just as readily as their male counterparts – in fact, they often take this as their distinctive prerogative.

When I was arrested on another occasion, that time for chalking on a wall, female officers asked me in an interview if I thought my behaviour was “ladylike”, mocked me for having “forgot[ten] to shave”, and described me as “tubby” in a witness statement with obvious satisfaction.

This undermines the liberal assumption that getting more women into institutions like the military and the police represents a feminist victory. When an institution exists to enforce and entrench hierarchical social relations, when racism and sexism are built into its DNA, the identities of individuals are not the issue.

One of the officers in my case was a Black woman. The fact that she was Black did not stop her carrying out a racist stop and search operation. That she was a woman did not stop her participating in a sexual assault, laughing about it with her sleazy colleagues, and lying about it in court.

Word from my lawyer is that the complaint against this officer (arising from the latest CCTV footage) can’t be pursued any further because she has left the police. I don’t know what led to her making that decision, but I’m glad to hear it and wish her well.

Divesting from these institutions, unpicking our lives and livelihoods from them, leaving them behind both individually and collectively, is what ultimately we all need to do.

Koshka Duff is assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Nottingham and editor of the essay collection Abolishing the Police.