Why Is Gen Z So Sex-Negative?

In Amia Srinivasan’s recently published monograph The Right to Sex, the philosopher recounts her experience of introducing her undergraduate students to the feminist sex wars of the 1970s and 80s, when the women’s liberation movement devolved into bitter internal debates over the ethics of pornography, sex work and sadomasochism. Expecting her students to be horrified by sex-negative feminism, Srinivasan is shocked by their sympathy. “Like the anti-porn feminists of forty years ago, [my students] had a heightened sense of porn’s power,” she observes – and like them, they are unanimous in viewing this power as negative.

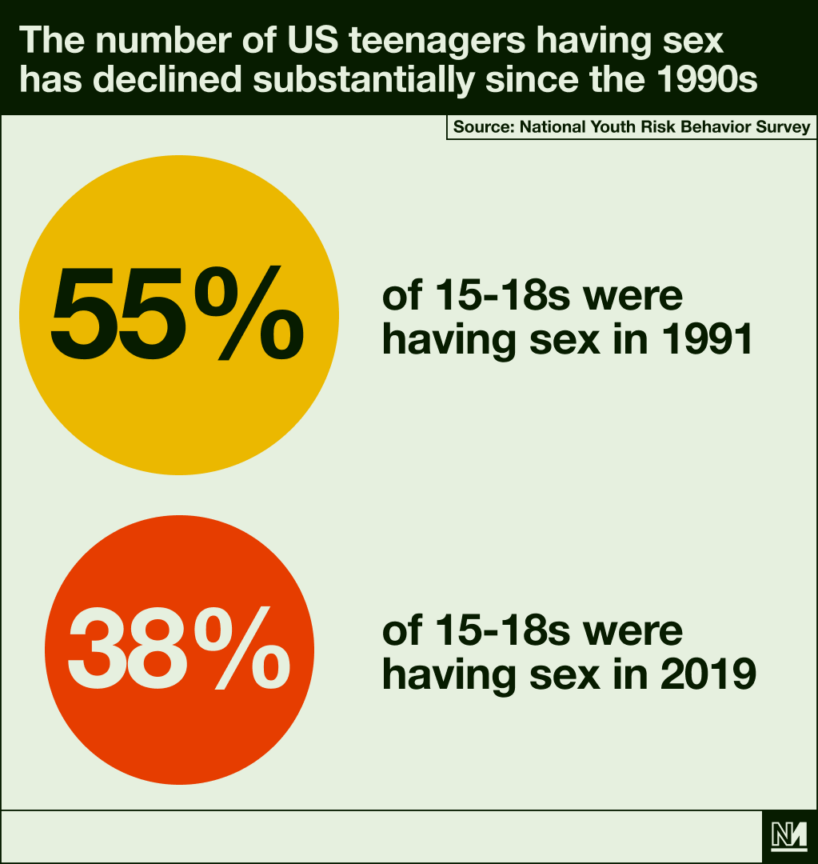

Not everyone will share Srinivasan’s surprise. Her students’ views confirm a widely-held belief that has by this point been elevated to a truism: that Gen Z, like the porn-sceptic feminists of the 70s and 80s, is a sex-negative generation. Evidence routinely cited to support this belief includes the so-called “sex recession”; TikTok’s #CancelPorn movement; and the annual intergenerational battles over kink at Pride. The idea that young people are abstaining from sex has even crystalised into a neologism: the Puriteen.

gen z stresses me OUT pic.twitter.com/Fwnj1XAKbR

— vanessa a. bee 🐝✌🏾 (@Vanessa_ABee) January 25, 2022

Yet beyond these disparate data points, there are clear rhetorical resonances between Gen Z and 20th-century sex-negative feminists. In articles for BuzzFeed and GQ, journalist Maddie Holden quotes a number of young people who profess to avoid sex for a number of reasons: because they find it “objectifying”, “dangerous”, “uncomfortable”, “fucked up and scary”; because they are “exceptionally concerned with trauma and consent”; because casual sex makes them feel “used”. Intensely personal as they may seem, such statements have a political history, one that risks falling from view when sex-negativity is treated as if Gen Z invented it.

By invoking objectification, instrumentalization, trauma, and consent, these young people – consciously or not – are using terms handed down to them by feminism. Their concerns closely mirror those of second-wave feminists about the way that (heterosexual) sex inherently objectified and degraded women. Turning to the historical antecedents of contemporary sex-negativity helps avoid the slip into apolitical prompted by generational exceptionalism.

During the sex wars, groups like WAVAW (Women Against Violence Against Women) and WAVPM (Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media) argued that pornography, sex work and kink were at the root of male violence. Termed “cultural feminists”, they generally refused to incorporate economic or racial factors into their worldview, and ascribed extreme power to media as a determinant of sexual behaviour, as if porn had instant brainwashing effects. They campaigned to shutter peep shows and illegalise porn, efforts being redoubled by the #CancelPorn TikTok movement. They allied with conservatives in order to introduce anti-trafficking legislation and ban the distribution of pornographic materials.

Mom, can you come pick me up? The entire country is rehashing the cultural discourses of the late 1980s/early 1990s as if we’re having satanic panic and feminist sex wars for the first time & I wanna go home and eat Golden Grahams

— 🍓 Camellia-Berry Grass 🍓 (@theCBGrass) March 29, 2021

At the same time, feminist sex-negativity was not always straightforwardly censorious. During the second wave, lesbian feminists in particular – invigorated by the political energy of Women’s Liberation – developed a kind of militant optimism about what they called “politically correct” sex. If done right, they argued, sex would be the opposite of violence: safe, harmonious and healing. It would even – as implausible as it might sound – advance the cause of feminism. This kind of utopian longing is voiced by one of Srinivasan’s male students, who – sounding eerily like a 1970s lesbian separatist – reportedly asked “whether it was too utopian to imagine sex that was loving and mutual and not about domination and submission”.

Scrolling through TikTok, I often find echoes of this optimism in the way queerness – and queer sex – is represented. While it might seem like a paradox that some young queers are expressing sex-negative views, the historical legacy of lesbian feminism proves that it isn’t paradoxical at all. Sexual pessimism, after all, can be a form of self-protection against disappointment – including the disappointment that sex does not deliver on the political optimism you bring to it.

gen z says sex is bad discourse, NFT discourse, top and bottom discourse… today BLOWS like fuck we need new material!! pic.twitter.com/kMnHlojofe

— Paul McCallion (@OrangePaulp) January 25, 2022

In her review of The Right to Sex, Caitlín Doherty asks: “Why should the opinions of a group of Oxford students, self-selectively interested already in feminism, be taken as representative of the mores of the general young adult population?”

The methodological problem Doherty identifies is common among those who write about sex for a mainstream, non-academic audience. Last year the American journalist Peggy Orenstein, known for her books about young people, gender, and sexuality, published an excerpt from her most recent book, Boys and Sex, in The Atlantic. The excerpt included the following caveat: “Though I spoke with boys of all races and ethnicities, I stuck to those who were in college or college-bound, because like it or not, they’re the ones most likely to set cultural norms.” In reality, this is not how culture works at all – although it is a rather convenient myth for the media class.

Srinivasan – who discusses Orenstein’s previous book, Girls and Sex, at some length in her chapter on young people and pornography – is far more attentive to nuances of social positioning. At the same time, in taking her students as representative of young people (she takes their views on porn seriously because they “are the first generation truly to be raised on internet pornography”), she glosses over factors likely to be equally if not more influential on their perspective than age alone.

Oxford undergraduates are largely white, middle- or upper-class, and from the UK. Among this demographic, anti-porn and anti-sex work feminism remains mainstream. One need only glance at the (Oxbridge-dominated) British media to find swathes of articles expressing horror at lads’ mags, OnlyFans, choking during sex and the provision of resources for student sex workers.

The concept of the “puriteen” is the most insane and perverted moral panic ever. Hundreds of 35 year olds on the internet freaking out because they think teenagers are insufficiently horny.

— Gender Calvinist ⚓ (@duns_sc0tus) December 6, 2021

Sexuality theory (and cultural analysis more generally) necessarily involves speaking in generalisations; a trend or tendency need not apply to everyone to be real. At the same time, generations are a particularly poor metric for meaningful analysis. This is particularly true because generations have, in popular discourse, come to function as a kind of stand-in for class. (Think of how millennials are invoked as both precarious and privileged, shut out of the property market for their avocado-eating lifestyles.)

The evidence is clear. Research by Srinivasan, Orenstein, Holden and others (including myself) all points to the existence of a real trend toward sex-negativity among the young. Yet attributing this trend to Gen Z obscures more than it reveals. More than anything, the idea that Gen Z is especially uninterested in sex erases a history – one that began as a split within feminism but whose reach far exceeds this origin. Indeed, just as earlier generations of sex-negative feminists ended up making bizarre alliances with conservatives in their efforts to criminalise pornography, so too are second-wave talking points today voiced by unlikely actors, including – but hardly limited to! – teenagers on TikTok.

Scapegoating Gen Z also belies the enduring hold of sex-negativity on our culture – belies the fact that distrust of sex in its many guises has never gone away. Rather than fretting over Puriteens, we would do better to acknowledge that the sex wars never ended.

Asa Seresin is a writer and PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania.