Abortion is a Crime in the UK

This July, a 24-year-old woman in Oxford is facing trial for having an abortion. The woman ordered the abortion medication Misoprostol online and took it at home in January of last year. She’s being charged under the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act (OAPA), which criminalises procuring abortion medication and inducing an abortion by any means. The charge carries a maximum life sentence.

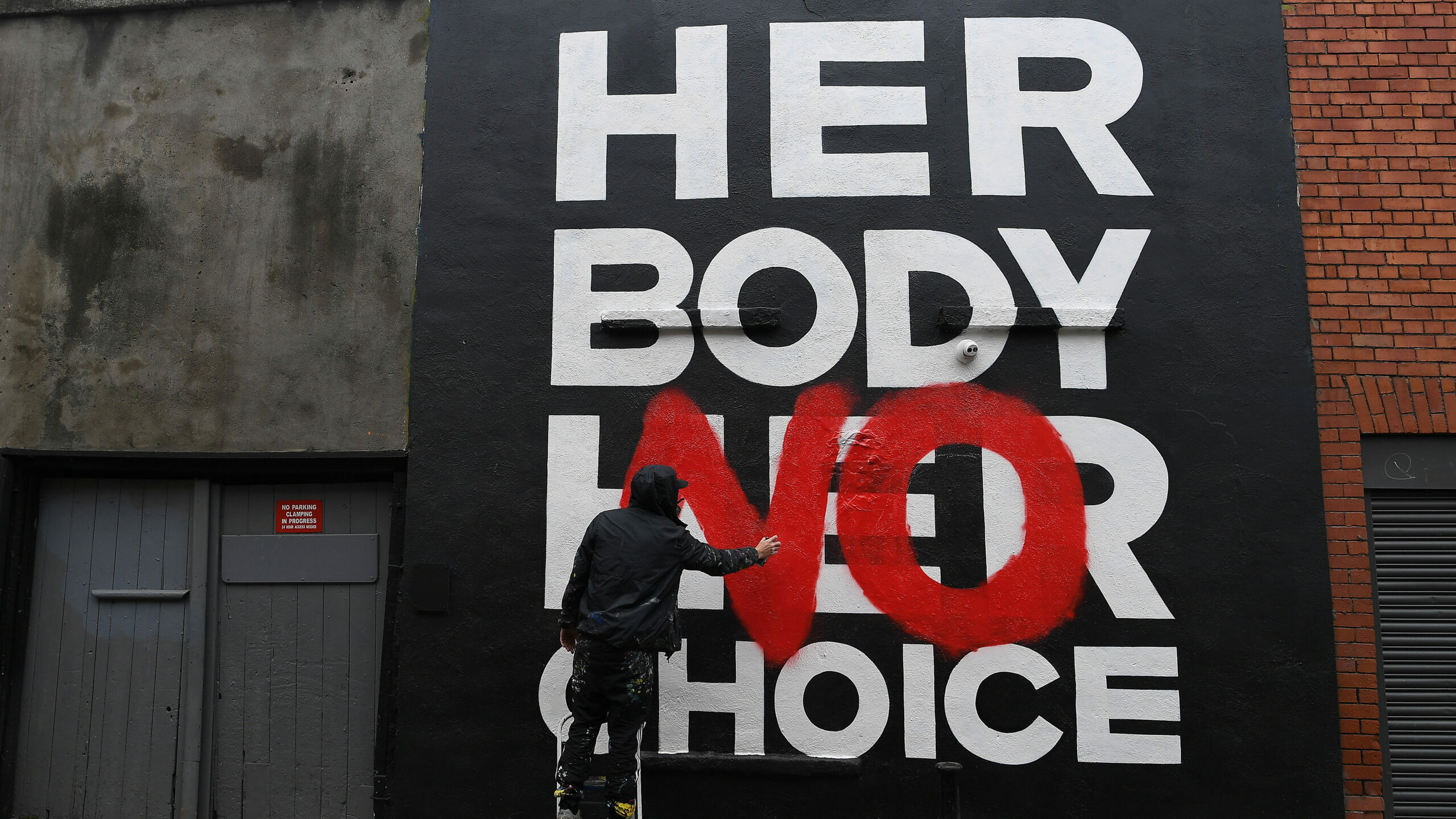

Abortion is a criminal act in the UK – except in Northern Ireland, where it was decriminalised in 2019. In the United States, by comparison – where abortion rights are under imminent threat – abortion is legalised. Katherine O’Brien is the associate director of the British Pregnancy Advisory Service, an independent healthcare charity providing abortions. She tells Novara Media that with the Supreme Court poised to overturn Roe v Wade, it has become apparent that people in Britain are generally not aware of “the precarity of our [own] right [to abortion]”.

The 1967 Abortion Act gave permission for doctors to provide an abortion if two clinicians decide that the pregnancy would hurt the pregnant person or their family’s physical or mental health more than if the pregnancy were terminated. Otherwise, abortion remains a crime in Britain. This legal framework is more restrictive than most European countries, where abortion is largely available on request, meaning not doctors but women have the final say on whether the pregnancy continues.

Though only a small number of people are charged under the act every year – no precise data exists, in part because those who induce their own abortions are not distinguished from those who perpetrate violence that causes a miscarriage – it’s still a relatively routine occurrence. In 2016, a Northern Irish woman was given a suspended sentence for taking abortion pills that she had bought online after her housemate reported her to the police. In 2012, a woman was jailed for eight years for giving herself an abortion. The woman had been denied abortion care for her pregnancy, which at the time was at 29 weeks, 5 weeks over the 24-week limit. By the time she gave herself an abortion using abortion medication, she was 40 weeks’ pregnant.

The US Supreme Court is expected to scrap Roe v Wade (which protects abortion rights).

Data from a Lancet study shows that in places with abortion restrictions, 75% of procedures are dangerous, incomplete or conducted by inexperienced personnel. pic.twitter.com/p9PLOKvDcq

— Novara Media (@novaramedia) May 5, 2022

O’Brien says there is “a real lack of awareness over the potential ramifications” of abortion’s criminalisation. Although during the pandemic it became legal to receive abortion pills by post if prescribed by a doctor, if someone were to take those same pills at a later date or pass them on to someone else, it would be a criminal offence. This is a concern, says O’Brien, “given that a lot of women will miscarry [or decide to continue the pregnancy] before the medication arrives” – meaning they are left with medication they don’t end up using on that occasion, but might use at a later date.

It isn’t just pregnant people that criminalisation hurts – it also stops medical professionals from doing their jobs. Under the OAPA, only doctors can provide abortions – even though some midwives can provide abortion medication in the case of miscarriage. There is “absolutely no reason why nurses and midwives wouldn’t be able to take a bigger role,” says Sean Rees, a doctor and campaigner for Doctors for Choice. “It’s only the legislation holding them back.”

Even those clinicians who are permitted to provide abortions may find the law off-putting, suggests O’Brien, who says that criminalisation has “a chilling effect on clinicians’ willingness to be involved in abortion care”: “There’s no other area of medical care where you are potentially risking imprisonment for signing a form incorrectly with no actual harm to your patient.”

Doctors’ fear is not unwarranted. In 2012, then health secretary Andrew Lansley ordered a series of investigations on abortion clinics. The inspections, says O’Brien, were “not about any concerns around quality of care … The idea was to go in and find incorrectly filled out paperwork that could then be used to prosecute doctors…” The period was “incredibly frightening … for clinicians who were just doing the right thing by their patients,” she says.

Rees argues that “the [way the] law exceptionalises abortion” means it is not “seen as [a] desirable” career choice for his fellow doctors. He adds that it prevents innovation in service provision, pointing to the fact that telemedicine – where patients take abortion pills at home, rather than having to take them in a clinical setting – was only permitted due to the pandemic, despite years of campaigning.

In being subject to criminal law, abortion is unlike any other medical procedure. Decriminalisation would remove criminal sanctions and place abortion care under the governance of healthcare bodies.

Under decriminalisation, abortion pills could be freely accessible from a pharmacy – as they are in Canada, for example.

Since 2013, the We Trust Women campaign – a coalition of women’s rights groups, reproductive rights campaigners and professional bodies – has been fighting for decriminalisation across the UK; since 2019 the campaign has been backed by the British Medical Association. Despite this – and despite the fact that nine out of 10 people in the UK are pro-abortion – the law remains unchanged. This is in part thanks to a small but vocal anti-abortion lobby within the UK, amplified by Tory frontbenchers such as Jacob Rees-Mogg and encouraged by Christian American groups. Since the Abortion Act was introduced in 1967, there have been over 50 attempts in parliament to restrict abortion – and if the US Supreme Court overturns Roe v Wade, there are likely to be more.

The criminalisation of abortion reflects a broader culture of women’s reproductive health being “regulated and monitored”, says O’Brien – something that is by no means the preserve of the US. Rees says that the criminalisation of abortion attempts “to use the coercive power of the state [and] the legal system, which we know routinely fails women, [and] the police, which we know are inherently violent towards women, to ultimately control not only if but also how, why and where people can access abortions,” says Rees. “I don’t think that should be tolerated anymore.”

Update, 28 June 2022: We have updated this article to include the context that the woman jailed in 2012 for self-administering an abortion was 40 weeks’ pregnant.

Sophie K Rosa is a freelance journalist and the author of Radical Intimacy.