2023 Will Be Make Or Break For The Scottish Independence Movement

A recent Supreme Court defeat has thrown a spanner.

by Jonathon Shafi

30 December 2022

Welcome to Scots Corner, a new biweekly column for 2023, focusing on Scottish politics.

As we leave 2022, Scotland is entering a new political environment. This is the consequence of the recent supreme court ruling, which officially decided that the Scottish government cannot hold an independence referendum on its own. This has disrupted the holding pattern around which Scottish politics has operated since the 2016 Brexit vote if not before, in which SNP politicians told the public, and many in the independence movement dared to believe, that a referendum was around the corner.

Now we can say definitively: there will be no referendum. Not without the agreement of the UK government.

This is a political reality that will take some time to fully establish itself. But it is already creating dilemmas for the independence movement, and the SNP.

It is no secret that there have been rumblings over the lack of an independence plan for some time. Certainly the supreme court, an organ of the British state, was not exactly fertile terrain upon which to prosecute the argument for Scottish self-determination. Moreover, the semi-permanent lure of a referendum became a useful device for the SNP leadership to shore up electoral support and subordinate criticism of its domestic failings.

The independence prospectus left a lot to be desired, too. Even pro-independence economists recoiled at the currency proposals, which would in effect leave Scotland without control over its own monetary policy. Instead, this would be governed indefinitely by the Bank of England until various stringent tests were met. Ironically, without an independently run central bank, EU membership would also be off the table – a fatal flaw, given how central opposition to Brexit has become to the case for independence.

Despite an increase in support for independence in the polls following the Supreme Court’s decision, there are deep-rooted strategic problems for the SNP. The plan now is to turn the next general election into a de-facto referendum, which feels somewhat half-baked. There is a lack of detail around the terms of such a proposal, with competing ideas in the wider movement as to how it should be handled; there will be a special conference to discuss the matter in March next year. The extent to which that discussion will be had outside of the parameters set by the party leadership – who seek to frame the debate as a question of democracy, rather than nail down the specifics of setting up a new Scottish state – remains to be seen.

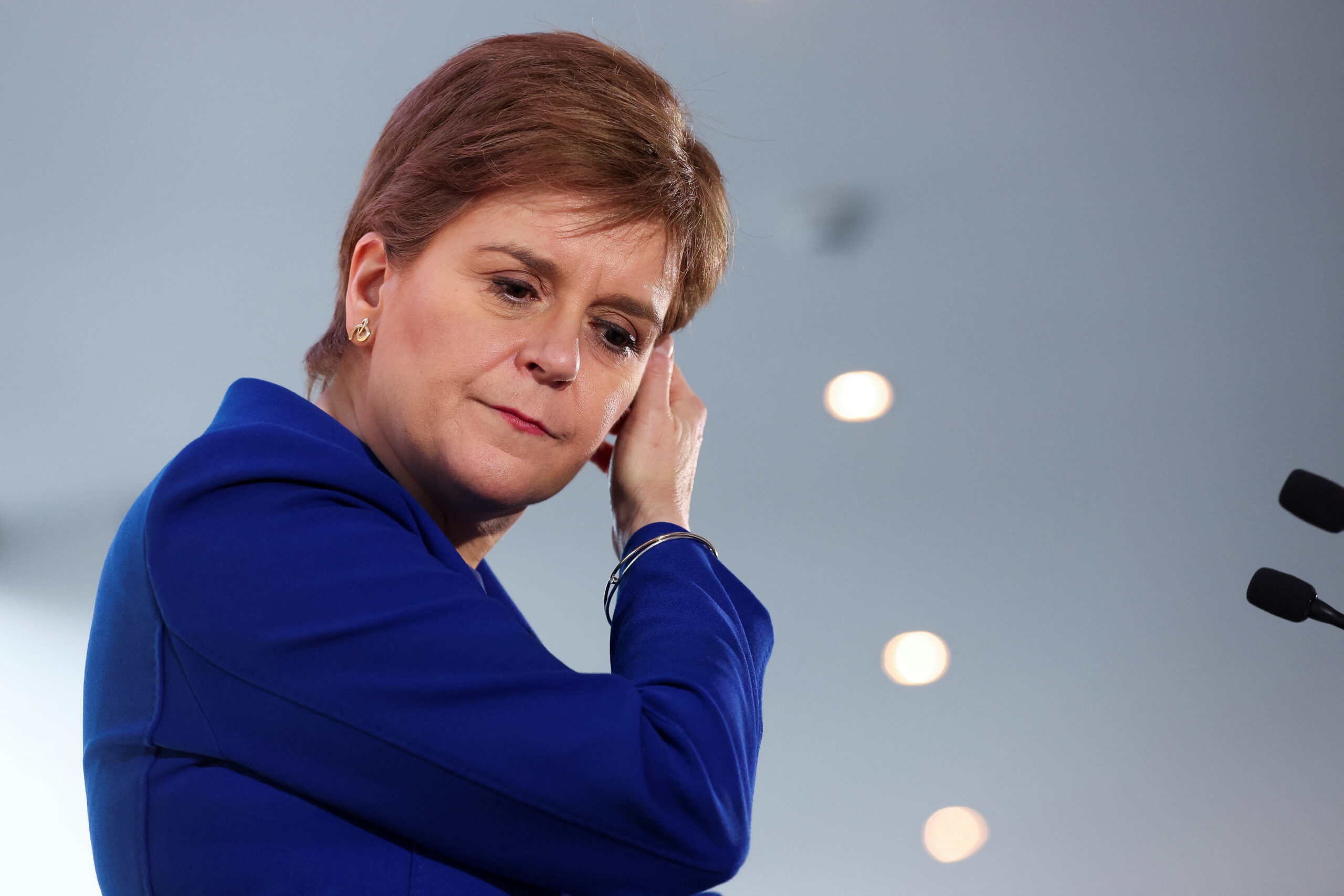

Some SNP MPs in Westminster are unconvinced. Among them is erstwhile SNP Commons leader Ian Blackford recently “ousted” by the young Aberdeen South MP Stephen Flynn, who has wasted no time in putting together a “new look” team. Flynn has already hinted that a “number of options” regarding the upcoming election are being floated, testing the authority of party leader Nicola Sturgeon. The sense of internal cohesion around the drive towards a new referendum is being replaced with a difficult debate about the way forward.

Other questions loom, too: what about Labour voters who support independence? Polling expert Professor John Curtice has often pointed out the importance of this cohort. Do all votes for all independence supporting parties add to an overall tally? Even if a majority is achieved, it would lack international recognition and domestic legitimacy. As a result, the notion that the SNP leadership will use such a platform to directly negotiate independence doesn’t stand up to any real scrutiny.

Former strategist for the 2014 Yes Scotland campaign Stephen Noon has other ideas. For him, the national question must be resolved more deliberatively. He advocates for a “conversation” aimed at bringing both sides together to chart a way forward and is uneasy about a plebiscite election. The crux is this: as of now, there is no unified line of march. The thinkers, personalities and organisations which prosecuted the 2014 campaign don’t exist in the same way now. Different challenges will require different interventions.

While the national question remains the central faultline that will dominate in the year ahead, there are other important developments. The wave of strikes involving rail workers, postal workers, teachers, coffin makers, housing workers, university staff and many others, has been met with embryonic yet well-organised movements of solidarity. Demonstrations have marched to picket lines in vibrant displays of support, while in places like Govanhill, roots are developing between the strikes and surrounding community campaigns.

We can’t be sure how this energy will evolve in the Scottish context. Westminster-based attacks on working-class living standards and union rights will interlace with democratic and constitutional questions. But the severity of the crisis will throw up all kinds of issues, resulting in confrontations not just with the Tories but the Scottish governing class, too. Earlier this month, the Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC) put demands on the Scottish government around land and wealth taxes, which were met with a tepid response. That similar proposals were previously put forward by the SNP trade union group, only to be excluded from the party’s conference agenda, shows the kind of tensions that we can expect to intensify.

Against this backdrop, the dynamics which have shaped Scottish politics are undergoing their first major shift since 2014. Many of the features which dominated that political cycle, not least illusions of an imminent referendum, are coming to an end. Big questions will be asked: where is the national movement going? How will the Scottish working class respond to events? Is the first minister preparing an exit from the political stage? How does the political and economic crisis manifest in Scotland? These and many other questions will be answered in this column in 2023. Stay tuned.

Jonathon Shafi is a columnist for Novara Media and socialist campaigner, based in Glasgow. He writes the weekly newsletter ‘Independence Captured’.