Artificial Intelligence Is Coming for Creative Workers Too

White collar creatives presumed they were immune from automation. They were wrong.

by Aaron Bastani

23 May 2023

When it comes to artificial intelligence, and its implications for work, it can be hard to discern “cope” from outright ignorance. One example is the refrain that creativity, and therefore the creative industries, are somehow immune from technological disruption.

This perspective was captured by researchers from innovation charity Nesta in 2015, when they wrote: “creativity is inversely related to computerisability”. If poetry is that which can not be translated, creativity is that which is incapable of automation.

Such an assessment is obviously stupid. Swathes of creative work have already been automated over the last five centuries: manuscripts with beautiful calligraphy gave way to moveable print more than half a millennium ago – a process which has only required less human labour ever since. It was the same with textile and ceramic manufacture after the early 19th century. Rather than creativity being something beyond automation, the very essence of the Industrial Age was deskilling creative artisanal labour.

So why would any intelligent person believe it? Because it is convenient and re-assuring. Automation in blue collar jobs was seen as inevitable, and sometimes uncritically celebrated, because the people writing the headlines and op-eds and commissioning the documentaries weren’t the ones losing out. And while they covered the plight of workers in manufacturing, it was simply more expedient to believe the same could never happen to them. Yet it increasingly seems that the opposite is true. Far from bypassing white collar industries, machine learning is coming for them first.

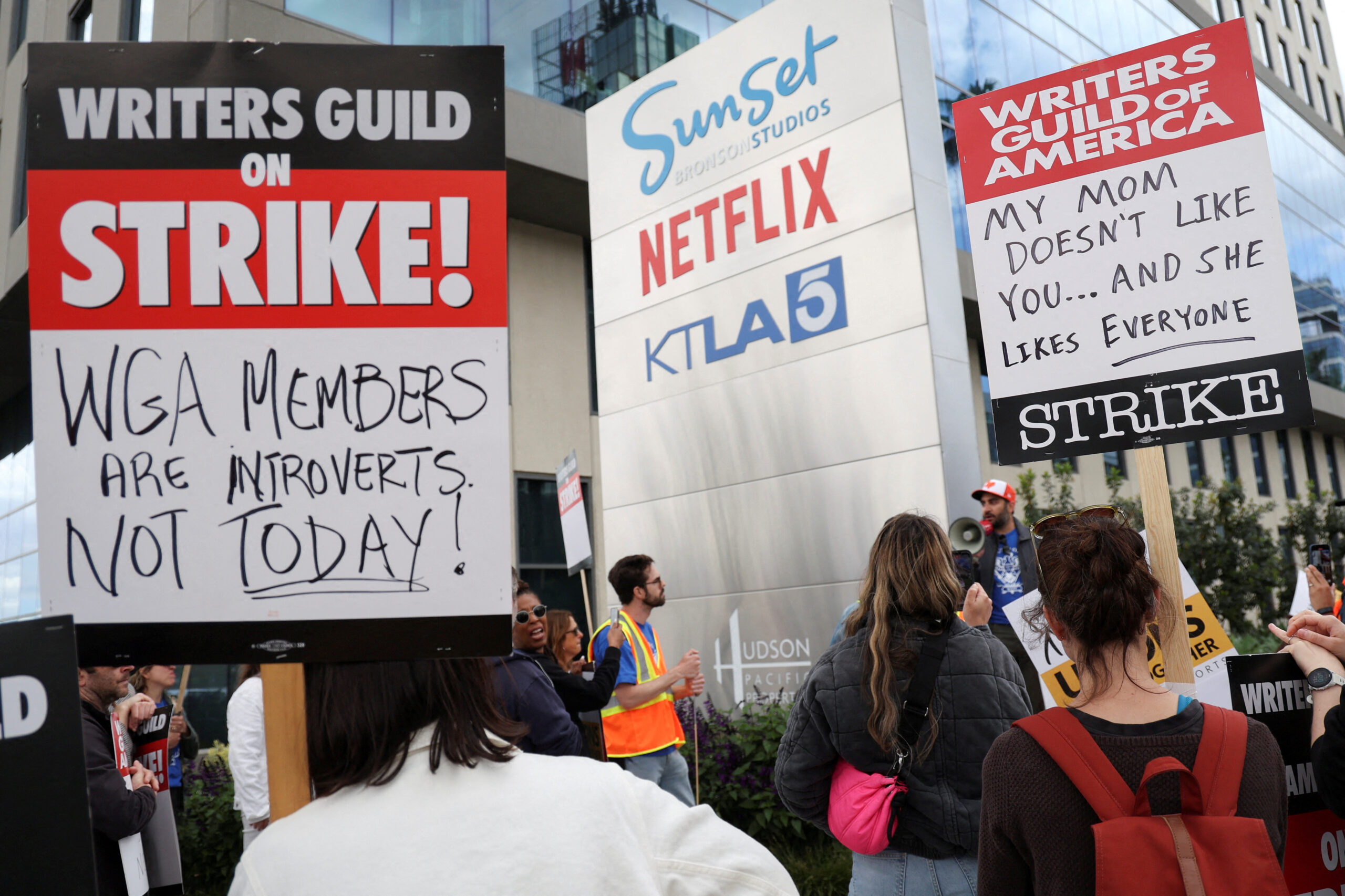

This is no longer speculation, with the regulation of AI part of a recent list of demands put forward by striking screenwriters in Hollywood. Among their proposals, the Writers Guild of America calls for the “regulated use of artificial intelligence”, adding that AI shouldn’t “write or rewrite literary material”, or be used to generate source material for humans to subsequently work on.

Equally important, given the nature of machine learning, which recursively improves as it is fed more data, is that material worked on by humans should not be used to train AI. The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers rejected those proposals. Their counter-offer? To hold “annual meetings to discuss advancements in technology”. A powerful industry actor refusing to accept constraints regarding the use of AI is no longer the stuff of science fiction.

That white collar jobs are those most exposed to automation was also put forward in a recent note by Goldman Sachs. It claimed that 18% of all global work could be automated by AI, a figure rising to 25% in the UK and US. But while the most vulnerable positions were in office and administrative work, legal services, architecture and engineering, the least exposed were in construction, installation and maintenance.

But even if machine learning can perform repetitive tasks like accountancy and legal services, or perform roles which synthesise information quickly, can it really intrude on the creative industries? After all, the value of screenwriters resides in that most human of resources, the imagination.

Until recently it was fashionable to answer in the negative. In his 2017 report on the creative industries for the UK government, Peter Bazalgette mentioned the word “automation” three times and “artificial intelligence” just once. Where the paper does reference technological change, it cites that same 2015 study by Nesta – which concluded that 87% of creative jobs have either no or low chance of being automated. Among the safest occupations, according to the study, were “PR and communication activities”, which stood less than a 12% chance of being automated, and computer programming – which was 8%. Fast forward to February this year, and ChatGPT3 (since surpassed by ChatGPT4, released in March) successfully passed the interview for a level 3 engineer at Google. A government report from just six years ago already looks as dated as a game of Snake on a Nokia 3210.

At the heart of all of this – from computer programming to writing shows like Succession and Ozark – is the question of precisely how “creative” creative work is. While an algorithm isn’t going to direct the next Citizen Kane, or author an epic to rival Tolstoy (at least not yet), it seems inevitable that machine learning will replace many of the tasks involved in creating things like games, novels, films and series.

This will start with the replacing of seemingly lower-level tasks – think translating code in programming or writing initial drafts of dialogue for a script – and progress from there. Hence the screenwriters’ demands – which are explicitly aware of how AI will improve over time.

Rather than the rise of the robots wiping out entire professions, machine learning will remove entry level positions in dozens of industries – meaning these jobs still exist, only there will be fewer of them. This is not only an issue regarding employment, but poses deeper questions about how to sustain the conveyor belt of future human talent.

Geoffrey Hinton, who recently resigned from his position at Google so he could “talk about the dangers of AI”, has already criticised the role of competition and commercial incentives when it comes to the technology. “I think Google was very responsible to begin with”, he opined at the Emtech conference earlier this month. But once “OpenAI had built similar things using […] money from Microsoft, and Microsoft decided to put it out there, then Google didn’t have much choice. If you’re going to live in a capitalist system, you can’t stop Google competing with Microsoft.” What is driving the technology isn’t a thoughtful weighing up of rewards and risks, of which there are many, but the economic prize of disrupting multiple trillion dollar industries.

The idea that capitalist competition creates consequences beyond the intentions of capitalists is nothing new. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx wrote how capitalist society had conjured up “such gigantic means of production and of exchange” that it was akin to a sorcerer “no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.” What Marx had in mind when he wrote those lines were the rising ziggurats of the Industrial Revolution, dotting the skylines of Europe’s cities. Yet more than 170 years later they read as even more apt in the unfolding race for AI. If the sorcerers are Google, Microsoft, Apple and Meta, then the key question is this: if any of them create a new form of intelligence can they control the consequences?

But we don’t need to go as far as speculating whether AI would, as Hinton muses, mean humanity is merely “a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence”. The fact that striking screenwriters are arguing against recursive learning in their industry is significant enough. If machines are set to swallow ever more creative work, as well as the repetitive data-crunching that will cost millions of jobs in industries like accounting and legal services, then the conclusion should be obvious: we will need a radically different kind of economic system. Recognising that doesn’t require the emergence of a real life Skynet.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.