Is Lula Bored of the Climate Crisis Already?

Brazilian president Luís Inácio da Silva – or Lula – is a political machine, well aware of the power of symbolic gestures, impassioned rhetoric and momentum-building policies. That is why during last year’s electoral race, knowing the reactionary voter would always choose his opponent, Lula made environmental and Indigenous rights the main tenets of his campaign.

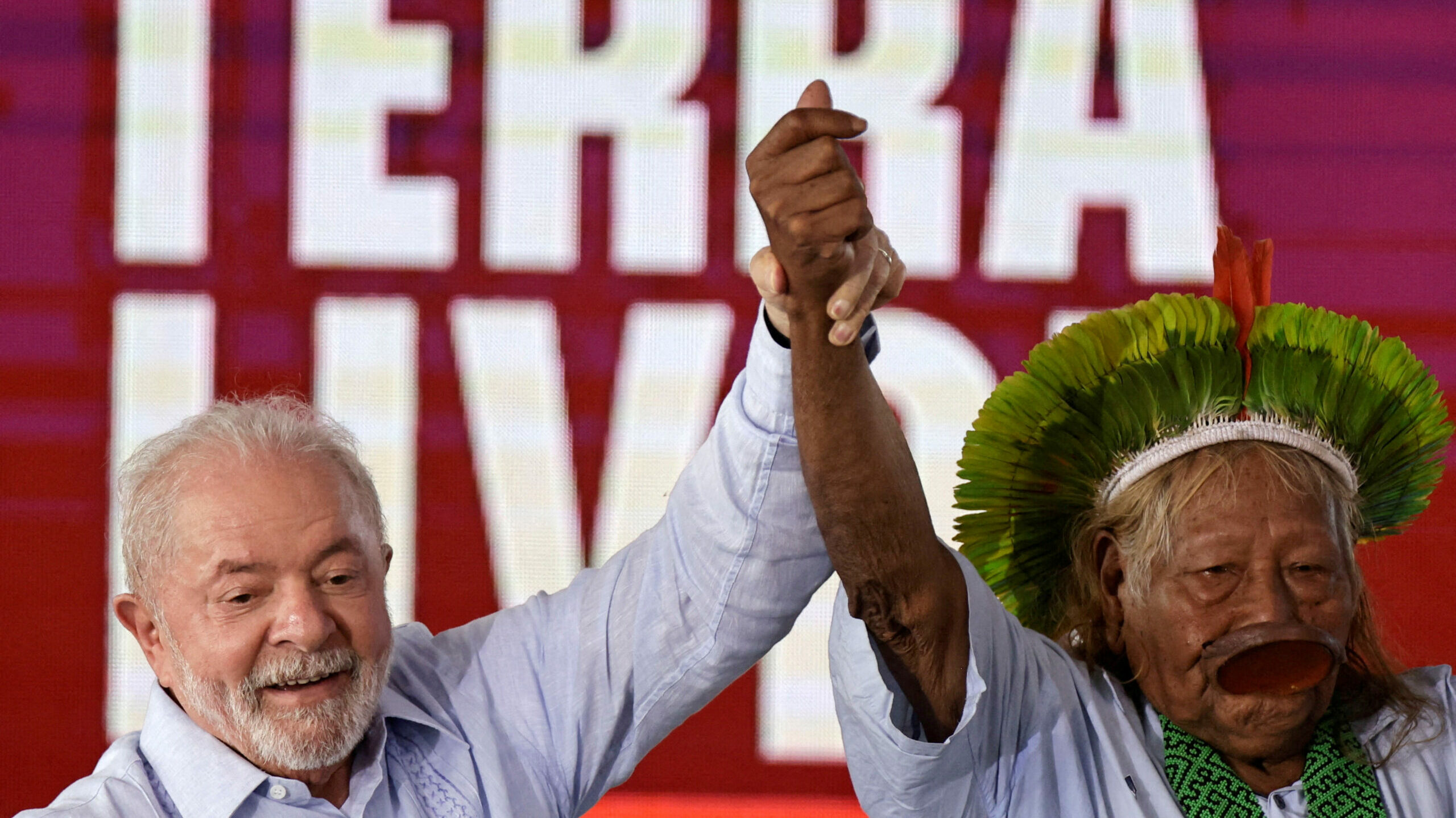

Upon his election in October, passionate pledges on ending deforestation became a hallmark of the Workers’ party (PT) leader’s speeches; as part of the inauguration ceremony in January, Lula walked up to the presidential palace holding hands with conservationist Indigenous leader Chief Raoni Metuktire. Progressive forces across Brazil rejoiced at this apparent U-turn from Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, marked by murderous anti-Indigenous policies and carte blanche to one of the most polluting and human rights-abusing industries in the country, agribusiness.

But an unfolding crisis in the capital of Brasilia has cast a shadow over Lula’s environmental and Indigenous promises. Over the last month, the conservative-dominated Brazilian Congress held a series of votes aimed at gutting both the environment ministry, led by Green politician Marina Silva, and the newly-minted Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, headed by the socialist Sônia Guajajara. What’s more, the Lula administration was slow to act in these departments’ defence, prompting questions about the steadfastness of his environmental agenda.

The agri-lobby.

Speaking to Novara Media, Brazilian political analyst Cleber Lourenço says he believes “the National Congress has its own plan for governance and tries to impose it regularly on the government.” Their influence comes thanks to the electoral success of Bolsonaro’s Liberal party, through which the so-called bancada ruralista (rural caucus) in the lower house, known as the Chamber of Deputies, grew to a record 300 members out of a total of 513.

This powerful bloc is backed by the agribusiness lobby with far more than just cash, says Lourenço: “For instance, for the parliamentary commission on the Landless Workers’ Movement, the livestock lobby has produced various materials on how to counter questionings, what is likely to be questioned, and they train deputies,” he says. “In my view, the attack on the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples is nothing more than imposing on the government the National Congress’s own agenda, which, in its majority, supported the former government.” He calls it a “war of attrition”.

It is perhaps not surprising that the conservative benches would put environment minister Marina Silva’s name first on their hit list. This is her second term as environment minister, having previously served under Lula’s first administration between 2003 and 2008. At that time, she pursued a politics of sustainable development and unyielding environmental protection, making powerful enemies in the bancada ruralista on the way.

Silva stepped down in 2008 citing “growing resistance” from her own government to her policies and initiatives. Over the past weeks, analysts have wondered whether this could be a moment of deja vu, but Silva’s rhetoric so far has targeted Congress rather than Lula. In late May, Silva told Brazil’s largest newspaper O Globo that “Congress wants a repeat of the Bolsonaro government”. Lula’s announcement earlier this week that he would lend extra support to the anti-deforestation programme in the Amazon, saw Silva’s social media injected once more with words of support for the President.

A new Lula?

When Lula’s victory over Jair Bolsonaro was finally confirmed, the question on everyone’s lips was: What kind of Lula administration will this one be? Would it be more like his first term, which saw heavy investment in social policies, or his second, marked by liberal conciliatory politics? Or will this be a whole new era and if so, what will it look like?

At first, it appeared as if Lula was readying a new chapter, spending much of his first days as president addressing the question of Indigenous rights and territory demarcation. The creation of the Indigenous Peoples Ministry led by the first Indigenous woman elected to Congress, as well as Lula’s trip to the state of Roraima during the health emergency in Yanomami territory, seemed to set the tone for a radically different administration, one ready to acknowledge and embrace Indigenous communities and their fundamental role in environmental rescue. But by March his attention had turned to international affairs – Brazil’s place in South American politics; summits of the Brics nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa); and his own role as peacemaker in the Ukraine war – leaving longtime ally Alexandre Padilha, technically the minister for institutional relations, as de-facto prime minister.

“Lula has lost the will to do domestic politics,” says Cleber Lourenço. But with a far more splintered Congress than during his first two terms, Lula can no longer count on a united government to run itself while he dedicates time to the international agenda. Lourenço argues that Lula needs to keep up with the times and the new dynamics at play. “Dilma Roussef was adverse to politicians, Michel Temer was adverse to voters and Bolsonaro was adverse to democracy,” he says, citing the last three presidents. “Congress has gained a lot of power with this.” Tackling this imbalance of power between Congress and the president “will inevitably require the figure of the president, a strong character” that can get involved and “leave the international aside.”

Environmental campaigners also believe the relationship between president and Congress needs to be repaired and managed, as soon as possible. “It is essential that the current president builds a solid base of allies both in the Senate and in the Chamber, so that we can advance environmental policies and ensure that Brazil returns to its leading role in facing the climate crisis,” says prominent youth climate activist Amanda Costa. And this working relationship isn’t just important in Brasilia: Costa argues that only through the collaboration of parliamentarians can Brazil expand its “mechanisms for participation and civil society-building”, especially those promoting the funding of “organisations on [Indigenous] territories and living the climate crisis on a daily basis.”

For now, the progressive, Indigenous and green politicians inside the Lula administration can still count on the president’s vision of making Brazil a leading nation in the fight against climate change. To truly beat the bancada ruralista, however, Lula will have to curb his internationalist ambitions. He will have to forget about Ukraine and take on agribusiness that is waging war on home soil.

Joana Ramiro is a journalist, writer, broadcaster and political commentator.