When Will We Start Fighting For Our Trains?

We stand to lose more than just ticket offices.

by Moya Lothian-McLean

13 July 2023

One of my favourite places to be is on a train. This is hardly original; odes to the romance of travelling by rail have existed for almost as long as passenger trains have chugged across the nation.

The history of rail travel in Britain is, of course, much less cosy than its image would have us all believe. It was not merely coal that powered early freight trains – roaring, dangerous beasts hauling raw building materials for industrial expansion – but colonial plunder. Regardless, the entrenchment of passenger rail travel was a revolution not just in transport, but Britain’s general structure, joining up settlements and driving urbanisation.

As a young person growing up in rural England with neither the financial resources nor a particular inclination to learn to drive, I spent a lot of time on trains. I won’t idealise the service provided by Arriva Wales which was, even then, overpriced, overcrowded, and often delayed. But as I’ve gotten older and depended even more on rail to deliver me to various domestic destinations for both business and leisure, the more expensive and unreliable the network has become.

The (un)managed decline of railways across England and Wales is well established: delays, cancellations, extortionate ticket prices and a failure to deliver key new rail projects plague a vital form of travel for millions. And yet, there is still further to fall.

Under new proposals announced last week by the Rail Delivery Group (RDG) – the body that collects all rail operators into one organisation – almost every rail station ticket office in England is set to close as part of a cost-cutting “modernis[ation]” drive. It’s the ideological endpoint of viewing rail travel as something to be profited from rather than a central and (smartly) subsidised part of state infrastructure.

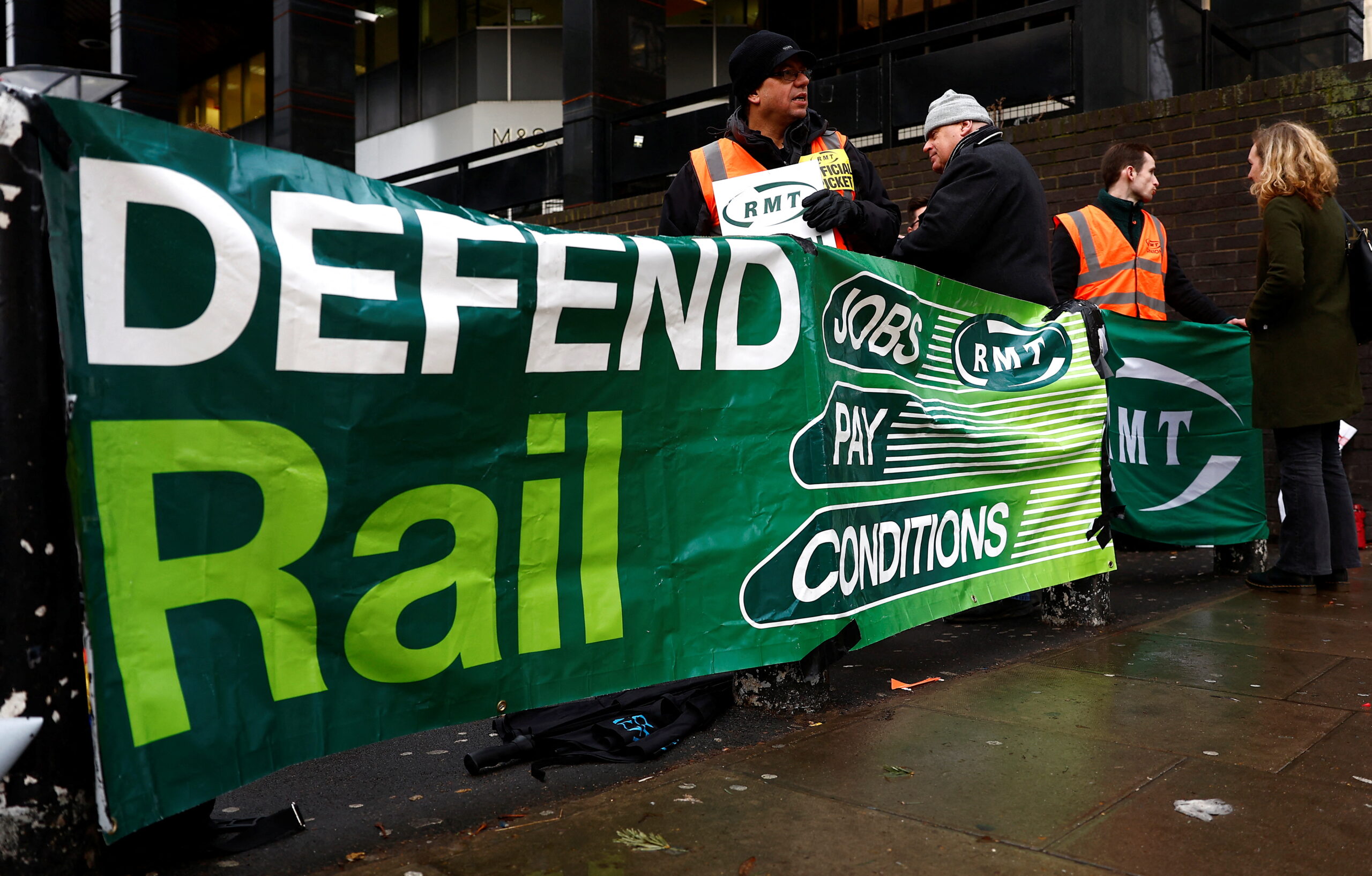

Train companies claim that shutting these offices won’t lead to any job losses; transport unions have called bullshit, saying legally required notices of possible redundancies have already started to dribble through to workers. Beyond lost roles, however, these planned closures represent a further shrinking of access and horizons. Ticket offices and their staff do far more than sell fares. As cuts have bitten and the presence of rail officials in stations has dwindled, these hubs double up as central and dependable points of information and assistance.

Journalist Taj Ali recently collated accounts from disabled train users outlining the necessity of ticket offices and their personnel for enabling their travel. “Ticket office staff give me instructions about where to walk safely, especially when there are a lot of passengers,” Kath, who is severely visually impaired, told Ali. “I don’t know how I’d cope if they disappeared.” Rather than a helping hand, roving ticket staff – RDG’s suggested replacement for static offices – would prove an additional hindrance to disabled rail users who may not be able to locate them. And as RMT general secretary Mick Lynch speculates, it’s likely many stations will suffer the complete absence of staff despite promises otherwise from train operators.

The rationale driving this latest measure to slash operating costs is a drop in passenger numbers since the pandemic – a decline unions say isn’t permanent. It’s also likely that it’s precisely expensive, irregular and inefficient rail services that have scared off potential train users who have the option to drive.

The wider upsides of rail travel barely need repeating. Accessible, affordable and expanded rail travel is essential for decarbonisation of our economy. The latest figures show taking the train results in 10 times less carbon emissions than an equivalent car journey, and 13 times less than a flight. Central government should be pushing to make train travel the fastest, smartest and most financially viable option of transport available.

Neglect of rail networks across England and Wales is driven by Westminster – and the further from London one gets, the worse service becomes. Lack of rail connectivity in northern England has had a “ruinous” effect on people’s lives, businesses and the economy, says Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham. Even in devolved nations, which oversee their own public transport, centralised funding allocations bind governments’ hands.

Nationalisation is only part of the solution. It matters who’s doing the nationalising, and how. The government is currently the biggest single rail operator in Britain – and yet with its for-profit mentality, all ‘nationalisation’ has delivered is more cut corners and slashed services. Of the remaining ‘private’ train operators, the majority are partly or fully owned by foreign investors, including the Italian and French state railways (where profits from British rail ‘management fees’ are invested into train services in their respective countries) and consortiums made up of Spanish and Australian transport behemoths.

The resulting landscape is a mess of contracted operators, subsidiaries and not-for-profit companies. Plans to streamline and simplify this disorder via the state-owned Great British Railways, although still far from ideal, have stalled.

So what now? In the short-term, the public has been invited to respond to consultations on the proposed ticket office closures (a vital forum; no matter the outcome, documented pushback against the plans is essential). But while shadow transport secretary Louise Haigh pledged last year that a Labour government would bring trains (and buses) back into public ownership, the party leadership has since been quiet on the topic – let alone willing to outline how its brand of nationalisation would differ from the government’s.

But trains remain a key site of struggle. They knit together people from across society (Tory voters, believe it or not, swing slightly towards rail nationalisation, and even arch-capitalists say the current situation is untenable). Meanwhile, the RMT and other unions have repeatedly articulated a roadmap to revive Britain’s railways, drawing on former London mayor Ken Livingstone’s push to revitalise the city’s flagging train networks. As Lynch said recently: “Transport itself is a liberation vehicle”. Pray God we find the energy to stop the Tories derailing our trains once and for all.

Moya Lothian-McLean is a contributing editor at Novara Media.