Filth: Coronavirus Has Shown That Cleaners Are Essential, but Labelling Them ‘Low-Skilled’ Legitimises Exploitation

by Eleanor Penny

23 May 2020

What threadbare freedom of movement had survived the previous decades of anti-migrant crackdown has now ended.

All those who fall under an annual pay bracket of £25,600 are deemed ‘low-skilled’ workers, and face punitive border sanctions, deportation, fewer rights and workplace protections, and no recourse to public funds.

Some ghoulish, perfunctory attempts have been made at glossing this as an economically enlightened way of filtering out the disposable crud, ensuring only the best of the best of a muscular, competitive, global labour market can elbow their way to the front of the queue; highly valuable humans get valued highly, and as for the rest – who cares?

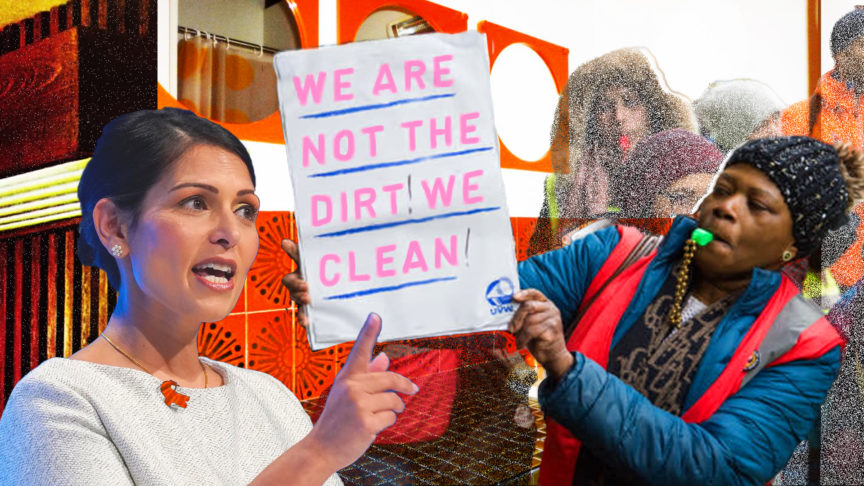

Amongst the ‘low-skilled’, low-value lives flung onto the legislative trash heap are those cleaners who professionally mop up the staggering and endless messes of our everyday lives, whose toil is one of the few things standing between civilisation and a gradual tsunami of filth.

Why then call cleaning – and indeed cleaners – low-skilled?

Only those cosseted by the luxury of idleness could call it easy work. It’s continual, physically demanding, exhausting, detail-orientated and hard to automate; many cleaners report suffering from repetitive strain injury, problems from using industrial-strength cleaning products, sky-high levels of stress and anxiety.

In truth, the label ‘low-skilled’ reflects little of the content of a job; its difficulty, its necessity, the skills actually required to complete it. Ever more prescriptive than descriptive, it’s a technocratic tool which allows governments and employers to justify terrible wages, and a ruthless high-churn work environment with no legal or social pressure to value the apparently menial lives of its menial employees.

It rubber-stamps a vicious cycle of low pay, precarious contracts and hyper-exploitation, allowing us to mistake being valued poorly for being low valued. The neoliberal language of human capital further collapses the distinction between ‘low-skilled work’ and ‘low-skilled worker’.

Those who have accrued employability through degrees, connections or previous high pay, have already proved themselves worthy of greater workplace entitlements. For the sake of a streamlined workforce, everyone else can – indeed, must – be instantly discardable, chronically replaceable.

Unsurprisingly this reinvents and embeds age-old inequalities where the working class – especially women, BAME people, migrants, and those with disabilities – are routinely locked out of ways to prove themselves ‘valuable’ to the tender ministrations of the border officer and the taxman.

It’s a useful tactic for dividing up a workforce, encouraged to compete for the socio-economic benefits conferred by a ‘high-skilled’ tag. It’s useful to build a mandate for the preponderance of workplace practices designed to make individual workers as precarious and replaceable as possible, driving down wage packets and employer liability.

The label of low-skill glosses rampant exploitation as the natural, proportionate response to a kind of work naturally, categorically less worthy of dignity, protection, and a living wage.

A crisis always reveals. Pandemic society has effortlessly withstood the temporary absence of hedge fund managers trundling off to their cotswolds bunkers to weather a minor apocalypse. Cleaners have been billeted to the frontlines, their work suddenly and mysteriously ‘essential’.

It might seem bewilderingly dissonant that such vital, uncompromisable work should be so easily traduced. Feminist theorists might have an answer here, having long observed that the daily toil of domestic work is exploitative and poorly paid precisely because it’s so earthshakingly important.

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve witnessed in relentless, horrifying technicolour that without domestic work, without cleaning work, other profit-making activities would be impossible. Disease and poor health amongst the workforce spirals, workplaces quickly overflow with trash, streets become impassable. This poses a few vital problems for those wanting to grease the gears of capital-harvesting – and the first is a problem of power.

Formal production is held hostage to the state of social reproduction. When cleaners strike – and cleaners, increasingly, are on the frontlines of the new union movement – industry is compromised. A workforce forcibly atomised, precarious, privatised, outsourced, in hock to irregular migration status, on their knees with exhaustion – is not only short-term more profitable, it is long-term less threatening.

The second is a problem of profit. If cleaning work was remunerated for the economic benefits it contributed to society at large – some estimates place this at £70,000 a year – the contemporary structure of the workforce would buckle under the demand for fair pay for unavoidable labour. Workerist feminists of the 1970s called wages for housework a ‘critical demand’ – a question unanswerable in the language of the current, whose lacunae speak volumes of the injustices built into our economy.

The unpaid labourer in private homes has provided a longstanding fix to the ‘problem’ of domestic work; delegating the task to hidden armies of people – usually women – obliged to toil away at the intimate coalface of modern civilisation, without any other means of sharing or lightening the work of making life.

The nuclear family unit was one of the key technological innovations of the industrial revolution; as was the blossoming cultural belief that women’s work was a lesser burden, to be lovingly cherished as a sacred feminine duty towards care. That this work is overwhelmingly a female preoccupation tempts some people to mistake domestic drudgery as a universal, flattening feminine experience; a sisterhood forged in the collective suffering.

But the burden of domestic work, like much of the world’s least glamorous, least remunerated and most vital labour, falls more heavily on women of colour and migrant women, who comprise a staggering majority of cleaners in the UK. Where middle class and upper class women can ease their private burdens by paying someone else, more often than not, cleaners will have their own shift of unpaid work awaiting them at home.

Gender is one workplace technology used to keep cleaning work cheap – but it is far from the only one. As the tectonics of the global labour market shift, racial fixes, border fixes, technocratic fixes and political fixes are drafted in to keep the people who do this work structurally more vulnerable to low wages and poor conditions, to load undignified, exploitative work onto people our Westminster classes habitually treat with little more dignity than the dirt they clean.

In many ways, cleaners have been used as a test population for broader techniques used to suppress wages and minimise business and government’s responsibility towards the wellbeing of the workforce – including outsourcing, platform work, zero-hours work, threadbare sectoral oversight, stripping people of a public safety net, and the use of punitive migration rules that put employees at the mercy of their bosses. Hostile anti-migrant legislation has helped unleash rampant levels of trafficking and modern slavery in the sector – and paid workers with irregular contracts can face devastating consequences for unionising or speaking out.

The government’s latest ingenious act of bureaucratic border cruelty is another twist of the knife. Every anti-migrant crackdown is answered with the commentariat distress-call of ‘but who will mop up our filth?’ – but it’s as misplaced as it is grotesque. It seems unlikely this will dry up the global flow of domestic workers – but it will doubtless make them more vulnerable to exploitation.

The pandemic briefly transformed low-skilled workers into essential ones – but the pomp and the plaudits did little to disguise the fact that essential also meant sacrificial. That if society could not continue without you, you would be far more likely to be exposed to vicious working conditions and a potentially deadly virus. Such is the paradox grafted onto the heart of our economic system, the casually vicious everyday, sharpened to a deadly point by the pandemic.

Every so often, the question ‘can you hire a cleaner in good feminist conscience?’ cycles through the broadsheet headlines – usually speaking volumes about both writer and intended audience. Suffice to say, it’s the wrong question; hiring a cleaner is neither anti-feminist treachery nor flag-waving subversion; the vast structural outrages played out in a combination of unpaid exploitative work and low-paid exploitative work won’t be solved by middle class women privately haggling with their own consciences about the right balance between the two.

We should ask instead how we transform the structure of work to properly value the vital work of cleaning, to properly defend those who do it. The answer doesn’t just begin at home – it begins at the border.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the fourth instalment in her series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.

Part one is here: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground

Part two is here: Racist Scaremongering Around Covid-19 Is Nothing New. We Have Always Blamed Racial Others for Disease

Part three is here: Space Junk Is Always Somebody Else’s Problem – But Eventually Someone Is Going to Have to Clean It Up