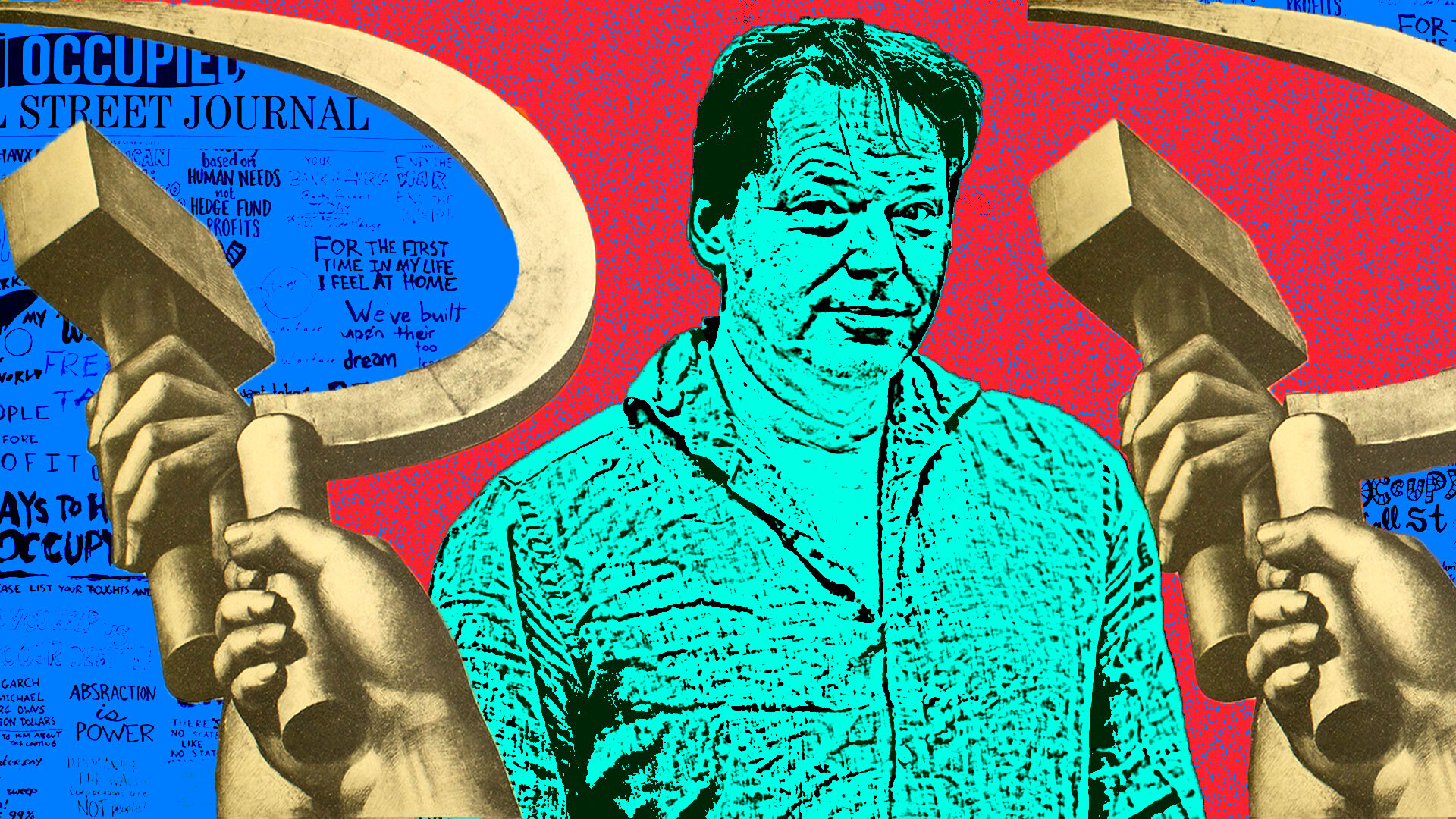

For David Graeber, Theory and Action Were Inseparable

He acted as if he was already free.

by Thomas Swann

7 September 2021

Perhaps fittingly, I heard that David Graeber had passed away while I was chairing a panel discussion at the Anarchist Studies Network conference. The conference was being held online and I was passed a virtual note. I made the announcement to those present – many of whom had known him personally, all of whom were inspired by him politically and intellectually – and virtual space was given over to collective mourning.

People shared stories of his selflessness and generosity, as well as his unwavering political commitment. There’s a word in anarchist politics that goes some way to encapsulating Graeber’s political contribution and his personal acts of kindness: prefiguration. Prefiguration is the bedrock upon which his anarchism was founded, and it helps articulate why he is so dearly missed – not just as a renowned academic, but as a comrade and, fundamentally, as a person.

‘We returned to our palaces, these Kingdoms, but no longer at ease here in the old dispensation, with an alien people clutching their gods.’

#DavidGraeber – a year today, may your soul rest in peace, as your thoughts play wild and free! pic.twitter.com/9zgAafudtd— David Wengrow (@davidwengrow) September 1, 2021

The art of acting as if you’re already free.

Prefiguration is one of those long and complicated-sounding words that anarchists love because it feels like something that is distinctively ours. It helps us define our collective identity as a movement.

But more than an identity, it is a call to revolutionary action; for immediate transformation in the behaviours and relationships of everyday life.

Prefiguration counters both the centralised strategy of a party taking over government, and the postponement of change until after the ‘Great Revolution’ at some unspecified point in the future, instead seeking to effect change through direct action in the here and now – or as Graeber so aptly put it, “acting as if one is already free”.

‘The principle of direct action is the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free.’ – David Graeber pic.twitter.com/fkPl5WtkJn

— Pluto Press (@PlutoPress) April 9, 2021

The term was first used in the 1970s to explain how social movements were organising themselves in this new way, in particular, the antinuclear movement of the 1970s and 1980s in the US.

Up until then, the dominant strands of the radical left had, for the most part, operated under a very specific framework since the end of the 19th century: a radical leftwing political party would take control of government and institute revolutionary changes to eventually pave the way for a radically democratic and communal utopia.

Anarchists such as Mikhail Bakunin opposed the strategy from its inception, while Emma Goldman and others witnessed its reality first-hand in the Soviet Union. Goldman, for example, described Bolshevik rule as a “sinister machine” that crushed “every constructive revolutionary effort, suppressing, debasing, and disintegrating everything”.

In part as a result of decades of revelations about the reality of life in the Soviet Union, many on the left came round to this way of thinking. People involved in anti-racist, feminist, environmental and a range of other movements increasingly argued that the centralised power of governments and parties was part of the problem; it was top-down and authoritarian rather than bottom-up and democratic.

Often, the political parties advocating for this strategy of achieving revolutionary change through taking control of government called themselves communist; many still do. But although prefiguration, and anarchism more broadly, stands in opposition to such a strategy, this does not mean that it is opposed to the idea of communism – far from it.

Graeber demonstrated this in his academic and political writing, arguing that prefigurative politics centres around a communism grounded in people’s lived experience – what he referred to as “everyday communism”.

Communism is all around us.

Expanding on anarchist geographer Peter Kropotkin’s concept of mutual aid, he pointed out that cooperation and sociability lie at the heart of how social life is organised. Collaborating on common tasks and sharing with others is fundamental to human life. This is the true meaning of communism, he argued; it is the banal, everyday reality of the famous slogan, “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs”.

David Graeber’s superb last essay written as an introduction to Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid + a brief autobiography. https://t.co/xFmOmTXA7M

— Camila Vergara (@Camila_Vergara) September 6, 2020

Graeber identified communism in everything from festivals built around sharing food, to jumping into a river to save a stranger from drowning, to providing someone with a light for their cigarette when they ask for one. No one gives you a light because they are following an order or on the basis that you will pay them a fee, he argued; they do it because communism animates our most basic interactions.

Indeed, the political idea of communism was not invented by revolutionary thinkers in the 19th Century. It was the communism of everyday life that inspired the political expressions we find in anarchism, Marxism and other communist traditions. As Graeber noted in Debt: The First 5,000 Years, “the peasants’ visions of communistic brotherhood did not come out of nowhere. They were rooted in real daily experience”.

Walking the talk.

In Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, Graeber wrote that the radical intellectual must take part in democratic and cooperative processes of understanding the world: “As much as possible, one must oneself, in one’s relations with one’s friends and allies, embody the society one wishes to create.”

I didn’t know him personally, but the collective remembrance that took place after his death – the stories and reflections of friends – paints a picture of someone for whom prefiguration and communism were not simply words, but a way of living and being in the world.

From his days as an activist in the anti-globalisation movement, to his involvement in Occupy Wall Street, to actively supporting the revolution in Rojava, Graeber helped to shape the strategies and tactics of anarchists and other radicals. But he did so in subtler, more quotidian ways as well: by supporting precarious workers at his university; by making himself available to speak wherever he was invited; through his many collaborative writing projects; in his day-to-day willingness to make time for just about anyone.

David Graeber was one of our most important intellectuals after the financial crisis. But what I’ll remember most is his humour, the way he’d oscillate between optimism and cynicism and laugh equally hard at both, how generous he was with his time.

— Ash Sarkar (@AyoCaesar) September 3, 2020

David Graeber’s academic contributions to anthropology and political theory have cemented his position in the pantheon of great anarchist thinkers. But he will be remembered, and missed, as much, if not more for his actions. He continued the proud tradition of anarchist theory made not just in seminar rooms and libraries but developed in collaboration with comrades on the barricades and in the streets as well. For him, theory was inseparable from action, a belief he enacted throughout his own life, prefiguring his politics, not only in grand political struggles, but also in small, everyday acts of kindness and resistance.

Thomas Swann is a political theorist working at Loughborough University and a member of the Anarchism Research Group. He is the author of Anarchist Cybernetics and co-editor of Anarchism, Organization and Management.

Part one is here: David Graeber Was Right: A Debt Free World is Possible

Part two is here: Sex Work Is Not a Bullshit Job

Part three is here: Anarchism Shaped David Graeber. Then He Shaped Anarchism

Part four is here: David Graeber Reminded Us of the Political Value of Anthropology

Part five is here: David Graeber’s Real Contribution to Occupy Wall Street Wasn’t a Phrase – It Was a Process