Britain Needs to Get Over Its Obsession With Flat Taxes

They’re outdated, regressive and deeply unchic.

by Ell Folan

27 September 2021

In 1911, chancellor David Lloyd George announced a brand new scheme: a system of “national insurance” against sickness and unemployment. Lloyd George’s idea was simple: employers, workers and the state would each contribute to an insurance fund that would pay for medical care and unemployment benefits in times of need. It was highly controversial at the time, and 110 years later, it remains so.

Earlier this month, the government hiked employees’ national insurance (NI) contributions by 10%. Progressives have complained that this hike, and indeed NI as a whole, hit the poorest hardest. They’re right – but NI isn’t unique in doing this. A whole host of flat taxes exist in the UK; all are extremely regressive. The recent controversy over NI has proven the unfairness not only of this one policy, but of our entire tax system. It’s time to rebalance the books.

Hang on – remind me why flat taxes are regressive?

A flat tax is generally one with a standard rate (percentage or absolute), as opposed to progressive taxes that impose different rates depending upon income.

Unless implemented with numerous exemptions, flat taxes are generally considered regressive in that they hit the poorest hardest. The rich might pay the same percentage, but their income is high enough that they don’t notice. Poorer citizens, however, do.

Contrary to popular assumptions about our supposedly progressive tax regime, many of Britain’s taxes are regressive flat taxes, including the BBC licence fee, value-added tax (VAT) and minimum alcohol pricing. I want to focus on the two that hit the poorest hardest: NI and council tax.

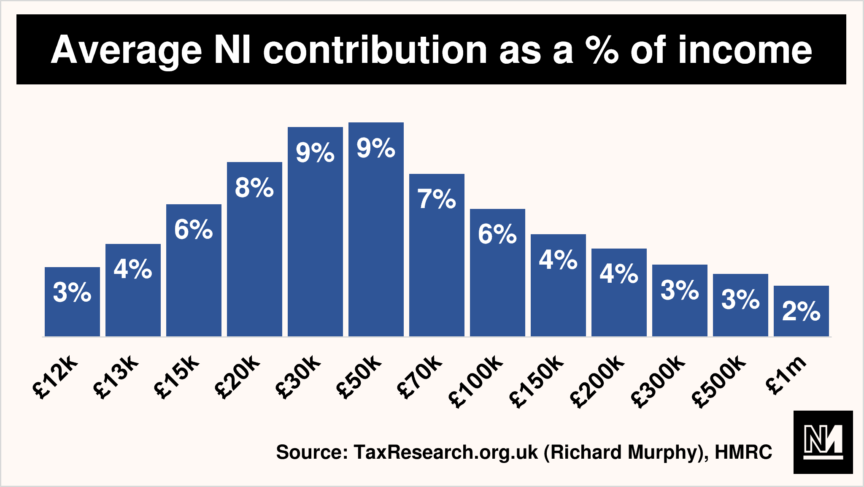

In the case of NI, if you earn over £5,700 a year, you pay a flat rate of 12%. But once you earn over £50,000 a year, your NI rate drops to 2% to take account of you paying the top rate of income tax. As a result, tax expert Richard Murphy estimates that the richest pay less than the poor.

NI’s regressive, flat nature is likely the consequence of its haphazard development: originally developed in the 1910s to fund pensions and healthcare for individuals, it was later extended to bankroll the NHS and welfare state when these were developed in the 1940s. NI was further altered by the UK’s increasing tendency to means-test benefits, undermining the link between NI contributions and state benefits by creating the possibility that workers could be refused benefits despite their historic NI contributions.

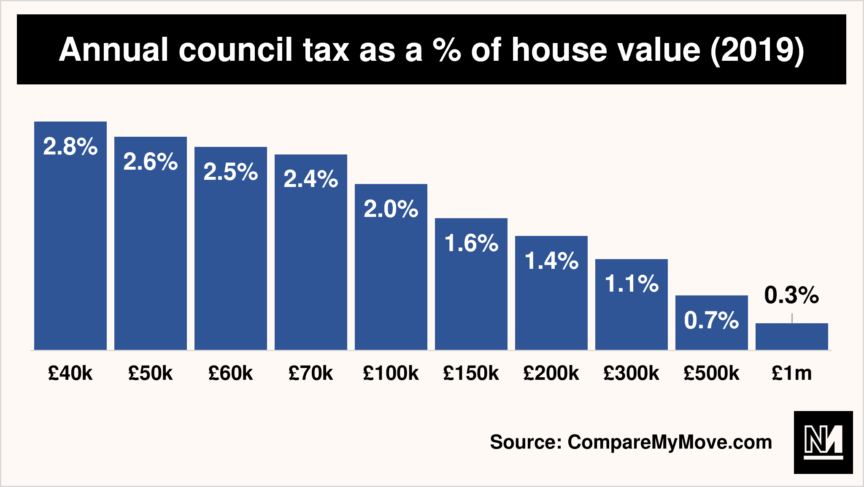

Council tax is regressive in a different way. Introduced in the 1990s as a tax on property to replace Thatcher’s poll tax, it is theoretically progressive (it increases with the value of the house). But in practice, it is not. Firstly, the UK government has not updated its housing valuation data since 1991. The effect, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, is that “properties are in increasingly arbitrary tax bands that may bear little relation to current reality [of the property’s value]”.

Secondly, because the valuation data was compiled 30 years ago, council tax stops increasing for houses worth over £320k – despite the fact that 770,000 houses were worth over £1m in 2018. As Laura Gardiner of the Resolution Foundation says: “Someone living in a property worth £100,000 pays around five times as much council tax relative to property value as someone living in a property worth £1m. This is exactly the kind of result that opponents of the poll tax wanted to avoid.”

The graph below shows the average annual council tax bill relative to a property’s value.

Okay, but what’s the alternative?

So even if we accept that these two major taxes are regressive, what can we do about them? Is it even practical to talk about reform? After all, NI has existed for over a century, and now provides a sum total of £142bn towards the welfare state. Council tax, meanwhile, has been in place for 30 years and currently provides 52% of local government funding. It is easy to see why most politicians – with the notable exception of Jeremy Corbyn, who backed replacing council tax with a progressive alternative – have avoided touching them.

When it comes to NI, the most direct remedy may simply be to scrap it, instead raising money through general taxation. This would likely require raising income tax, and though this would leave most people better off, politicians will be hesitant – raising taxes is considered an unpopular move, and indeed the Tories’ NI hike has hurt them in the polls.

Another, more practical option would simply be to make those who earn over £50,000 pay the standard rate (12%) instead of the reduced rate (2%) – a report from LSE suggests this alone would raise £20bn.

The possibilities for council tax reform are many. One is to abolish this outdated system entirely and replace it with either a property tax (a percentage of a property’s value) or a land value tax (based on the estimated value of the land, not the building), both of which would be more progressive. Another alternative is the simple option: re-valuing houses based on 2021 prices and/or adding higher valuation bands to the existing system. Murphy backs adding five new bands, saying: “In one easy move we get a more progressive tax, a disincentive to property price speculation, and a pool of new funding.”

There is a reason that successive governments have not done this, however: no politician wants to be the one who sends inspectors around everyone’s homes.

Conclusion

Flat taxes, then, are clearly regressive. Yet they continue to make up a sizeable portion of state funding. Why?

Lack of political will is one reason. Designing new taxation systems is boring, expensive, and time-consuming, and the impact of the changes won’t be seen immediately.

Another reason is simply ideology. For at least the past half-century, our country has been led by people who don’t want to tax the rich. It’s time they took AOC’s advice.

Ell Folan is the founder of Stats for Lefties and a Novara Media columnist