‘Fuck You, It’s Class’: How Welsh Pride Went Mainstream

‘Wales has so much history, culture and character that most people never hear about.’

by Gina Tonic

6 October 2021

It’s been almost ten years since I moved away from Mountain Ash, a small town deep in the valleys of south Wales, to Manchester, one of the biggest cities in the north of England. There are many obvious differences between the two places – the population counts, the names for a bacon roll (Mancunians call it a ‘barm’), and for me, there was a huge culture shock in moving from one place to the other. In the years following my move to England, however, I not only came to learn the key differences between England and Wales, but the importance of being proud of being Welsh.

This journey is not a singular one. From growing interest in the national football team to the emerging Welsh independence movement, to simply an increasing desire to connect with other Welsh people on social media, over the last decade, Welsh pride has seen a real resurgence. How has this happened?

What is Welsh pride?

“We’re a small country, but we have a huge heart.” Jessica Davies, a Welsh-speaking BBC and S4C presenter, explains that on a surface level Welsh pride is simply pride in being from a small, tight-knit community. Indeed, since moving to England, I’ve regularly been asked if I know someone from Wales, and after laughing at the suggestion I’ve then found that I do in fact know them (or, at the very least, we have five mutual friends on Facebook).

This fosters a strong sense of pride in Wales’ most famous cultural figures. “There’s this very close-knit feeling towards footballers and musicians because more often than not they’re literally someone from down the road,” Emma Garland, Vice culture editor from Pontypridd, elaborates. “Someone’s grampi used to drink with them, or they showed up to your cousin’s birthday party because a friend knows their aunt. You’re basically never more than two degrees of separation away from the person on TV. The sense of community is still there a lot of the time, even when the person in question is someone like Anthony Hopkins.”

Garland’s words chime with my own experience of Welsh celebrity culture. Infamously in my hometown, Tom Jones played in Mountain Ash Working Men’s Club before his rise to fame, and was once paid during an interval to not finish his set. Ask anyone’s nan from back home, and they’ll tell you they were there that night. And did you know they used to go dancing with Tom down Treforest as well?

But Welsh pride also has a political dimension, of which distinctness from ‘Englishness’ and ‘Britishness’ is a key part. When thinking of Britishness, the average person doesn’t think of daffodils, bonnets or Sosban Fach. They don’t think about the heritage of Tiger Bay, and few know that the stories of Merlin and King Arthur are based on stories from The Mabinogion. Britishness, Davies argues, is seen as “union jacks, English Bulldogs, the royal family and the likes of Boris Johnson.” These associations feel unrelated to the Welsh experience because being Welsh feels unrelated to Britishness. Welsh pride, by contrast, is pride in our own culture, traditions, language, flag and heroes.

For Cardiff-born writer and presenter Danielle Fahiya, one important distinction is that Welsh pride is a lot more inclusive than English or British pride. “We use the word ‘hiraeth’ to describe a deep longing for home in the context of Wales or Welsh culture – and Welshness differs from the way in which you have to qualify your Britishness either by ancestry or place of birth,” she explains. “As a grandchild of an immigrant, I feel that specific parts of Wales – in particular Cardiff and Barry Docks – were relatively safe places for immigrants to settle.”

What’s more, there’s a sense that Welsh pride is less about ruling over others than English or British pride. “This isn’t to say that Wales hasn’t participated in colonialism, but that Wales doesn’t take pride in its colonial history in the way England does as part of the British empire,” she continues. In fact, Wales is itself often referred to as “the last English colony”, and so Welsh pride is often invoked as a bulwark to Britishness “due to the fact some people feel that we are still England’s possession”.

Like anywhere in the UK, Wales is hardly exempt from racism – something often brushed over when talking about Welsh pride and independence. Fahiya cites the 1919 race riots, the hanging of Mahmood Mattan and the case of the Cardiff Five. Only this year there was the case of Mohamud Mohammed Hassan, a young Black man who died shortly after leaving police custody in Cardiff, sparking Black Lives Matter protests in both Cardiff and Newport. However, in trying to understand how Welsh and English identities are formed in the context of racism, we can’t treat the histories of these countries as one and the same.

The rise of Welsh pride.

There are a number of political factors that have led to the resurgence of Welsh pride over the last decade – nothing more so than a growing feeling of being screwed over by the English. “England has been giving us crap for decades, but now Welsh MPs have been reduced to 32 in the House of Commons,” Garland explains. “Meanwhile, half the country [Wales] is rapidly becoming a holiday resort for people who see a bit of the Pembrokeshire coastline advertised in The Telegraph and buy a portfolio of holiday lets, which pushes out local and typically Welsh-speaking communities.” These aren’t new problems, Garland notes – people in west Wales used to burn down second homes – “but as with everything, it’s felt more keenly in a wider context of economic inequality” to the extent that “people leave Wales for uni or work opportunities that just aren’t available to them at home.”

For Garland, it’s the awareness of this inequality that feeds Welsh pride. “Welsh people tend to be very proud of being Welsh regardless of our relationship to the union, but with younger generations […] Welshness is more closely linked to an awareness of power imbalance and a sense of being fucked over by dispassionate politicians both in Westminster and the Senedd,” she explains. “Overall it’s perseverance in spite of so much blatant injustice that defines Welsh pride. Everyone loves an underdog.”

It feels uncomfortable that workers, industries, unions, and leaders across Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the north of England called for a furlough extension for months and it only happened when the south of England went into lockdown.

— Miriam Brett (@MiriamBrett) November 1, 2020

Most recently, Covid-19 has exemplified both the differences in the political leaderships of England and Wales and Wales’ unjust treatment by Westminster. As stricter Welsh restrictions were criticised for excluding English travel, the Welsh people rallied behind first minister Mark Drakeford and his response to the pandemic. Notably, furlough extension requests by Welsh ministers were initially denied by politicians in Westminster, who then U-turned on this decision when it was deemed furlough extensions were needed in England. This served to deepen the sense amongst Welsh people that the UK government prioritises England over Wales, and furthered support for and pride in Welsh leaders who spoke out on the issue.

But beyond the purely political, there are also a number of key cultural factors that have contributed to growing Welsh pride in recent years. First, there’s been the rise of Welsh football. Since its inception in 1958, Wales had never appeared in the European championship. This changed in 2016 when, as a surprise to casual spectators of the sport, Wales got further in the Euros than England. Sporting success is renowned for its ability to invoke pride in its supporters and, in this case, football’s impact on Welsh pride was certainly palpable.

In 2021, Wales made it into the Euros again – before England went on to make it to the final. Welsh pride might not have been so widespread this time around, but social media served to connect Welsh football supporters nonetheless. On Facebook and on Welsh Twitter, Welsh people came together to jibe at the English, with countless memes mocking England’s superiority complex pushed out across newsfeeds.

Another example of how digital communities have helped to make Welsh pride mainstream is the increasing accessibility of Welsh history. Over the last few years, Twitter pages like Yr Hanesydd Cymreig (The Welsh Historian) have attempted to show not only the depths of Welsh culture, but the ways in which our culture was robbed from us. In the 19th century when, for instance, 80% of Wales’ population spoke Welsh as a first language, and, more often than not, didn’t speak English at all. The English education system, however, took to punishing children who spoke Welsh in classrooms, and the language has been lost with every generation. By highlighting these injustices, Welsh people have been able to learn the importance of our language, our culture and our pride via easily digestible posts – alongside provoking righteous anger at those who mock the Welsh language.

Yes Cymru?

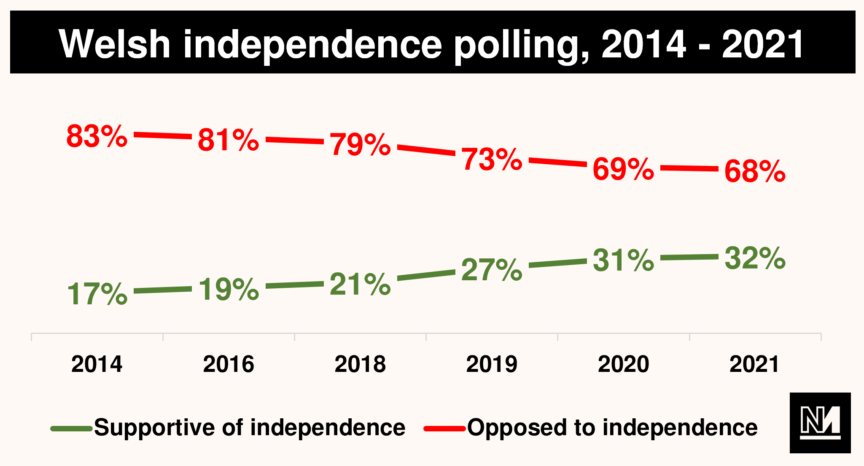

It’s no surprise that the resurgence of Welsh pride has come hand in hand with a growing interest in the idea of Welsh independence. Over the past five years, Wales has seen the rise of the non-partisan ‘Yes Cymru’ movement, which is now one of the largest political membership organisations in the country. Its success is in the figures: one recent poll put support for leaving the UK at 40% – the highest level of support for Welsh independence ever recorded.

Recent independence movements in other parts of the UK have no doubt boosted the cause in Wales. The last decade has seen Scottish independence go from an underground debate to a real political possibility, with one referendum in 2014 and another likely on the horizon. Watching this occur has made Welsh independence – a topic I had never discussed in real life or online prior previously – seem like a sensible demand for those in Wales with a strong sense of Welsh pride.

However, it’s important that the Welsh independence movement doesn’t run only on anti-English sentiment, but that it directly benefits marginalised groups within Wales that suffer under UK policy-making. This includes working-class people who have suffered savage austerity cuts, people of colour facing police brutality within Wales, and the trans community, who recently received an apology from Plaid Cymru following transphobic remarks from one of the party’s MPs. Thankfully, online activists like POC4WELSHINDY are pushing for inclusivity to be central to the Welsh independence movement, championing the belief that Welsh pride should reflect Wales’ diverse population.

‘Fuck you, it’s class.’

“It was Gwynfor Evans [the first Plaid Cymru MP] who described ‘Britishness’ as “a political synonym for Englishness which extends English culture over the Scots, the Welsh and the Irish.” I would agree with that,” Garland recounts. “But growing up, I remember there being a real sense of misery and shame attached to the Valleys – the accent, the assumed lack of education and the extreme deprivation of the area. That ‘land of my fathers and my fathers can have it’ attitude stuck with me massively for a really long time.”

For Garland, along with many other young Welsh people, that has now changed. “Welsh pride to me now is a feeling of ‘fuck you, it’s class’. Wales has so much history, culture and character that most people never hear about,” she continues. “Welsh pride is taking the time to learn what all that is – even if it’s just your own family history – and experiencing that quiet rush of connection wherever you see it.”

Gina Tonic is a freelance culture journalist based in Manchester, originally from the valleys in south Wales.

Breaking Britain is part of Novara Media’s Decade Project, an inquiry into the defining issues of the 2020s. The Decade Project is generously supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (London Office).