Is Welsh Independence Really on the Cards?

‘Indy curiosity’ is certainly on the rise – but we could be stuck in stalemate for some time yet.

by Daniel Wincott

6 October 2021

In May, Wales went to the polls for the 2021 Senedd election. Notably, although the official position of Welsh Labour – the largest political party in Wales – is that Wales should remain part of the UK, in this election the party selected three candidates who openly support Welsh independence.

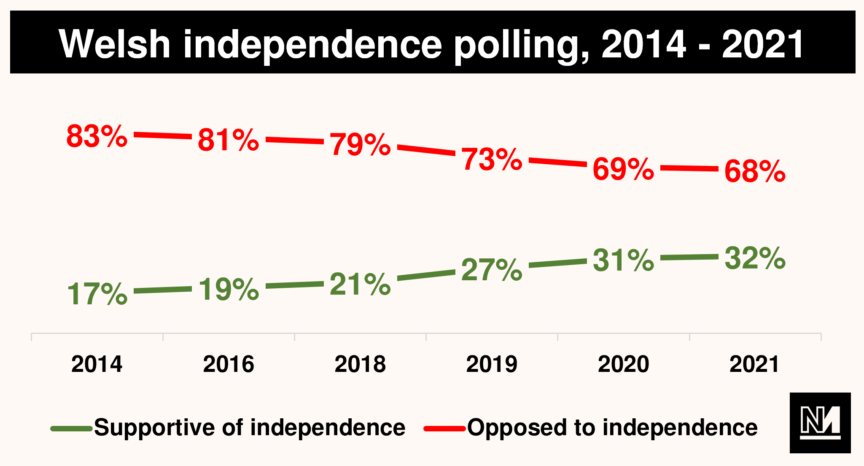

Indeed, the question of independence is being discussed in ways unimaginable even a decade ago. More and more people are becoming ‘indy-curious’, and though opinion polls continue to show a clear majority for staying in the UK, the size of that majority may be shrinking. One poll in March 2021 even put support for independence as high as 39% – though around 30% (excluding ‘don’t knows’) is a more consistent percentage. Even this, however, suggests support for independence has picked up over the last couple of years.

So why is the Welsh independence movement growing? And is it really on the cards?

Complex identities.

To understand changing attitudes towards Welsh independence, we first need to look at how people in Wales understand their own national identities. The picture is fiendishly complex. Over 50% of the population identifies as Welsh – either exclusively (25% to 30% of the population) or as both Welsh and British (20% to 25%). Around 15% of the population identifies as exclusively British – three fifths of them ‘British, not English’, and two fifths ‘British, not Welsh’ (a group concentrated in Monmouthshire and Pembrokeshire). Nearly 20% of the population identifies as English, as people who come to Wales from England tend to bring Anglo-British patterns of national identity with them. Between 15 and 20% of the population fall outside the above identity groups, either holding some other national identity or no such identity at all.

Attitudes towards independence in Wales are, unsurprisingly, refracted through these heterogeneous national identities, with support for independence historically concentrated heavily amongst those who identify as exclusively Welsh. Meanwhile, those who identify as British and/or English rather than Welsh, alongside those who feel both Welsh and British, have on the whole seen little reason for Wales to leave the UK.

Wales’ main political parties align themselves differently on the issue of independence. Plaid Cymru, ‘the party of Wales’, is a nationalist party that sits broadly on the left of Welsh politics and holds just 13 of the 60 seats in the Senedd. Plaid backs independence, and draws the majority of its vote from independence supporters. The Welsh Conservatives hold 16 Senedd seats and, broadly speaking, back the devolution status quo while expressing strong support for the union. Welsh Labour holds 50% of Senedd seats, and while the party is pro-union, it has proposed far-reaching reforms of the UK constitution with the aim of entrenching devolution by defining the UK as a voluntary union of nations.

But is there a change in the wind? James Griffiths’ analysis of Welsh Election Study data shows that independence is extending its appeal beyond people who identify as exclusively Welsh.

First, between the Senedd elections in 2016 and 2021, a large section of the Welsh electorate converted to supporting independence. Although not identifying as strongly as Welsh as long-standing proponents of independence, this group does give priority to a Welsh identity – but it also identifies much more strongly as British than longer-standing supporters of independence.

Second, short of conversion to backing independence fully, a larger group of people have also become somewhat more supportive of independence. These ‘indy-curious’ people, Griffiths notes, “report similar (and strong) British and Welsh identities”. The immediate prospect of independence remains remote, but its appeal is growing.

How did we get here?

Although there’s a lot that’s happened in recent years that’s given rise to ‘indy curiosity’ in Wales, the independence movement has much deeper roots. If the Anglo-Scottish union preserved the autonomy of Scotland’s key institutions – the church, the law and the education system – Wales was formally absorbed into England’s institutional systems more fully, and much earlier. At the popular level, though, Wales remained distinctive socially, religiously, culturally, and – most notably – linguistically. This distinct identity was reinforced both through the creation of new national institutions, such as the federal University of Wales in 1893, and by loosening ties to England, such as through the disestablishment of the Anglican church in Wales. Even so, Wales remains a poorly understood part of a highly centralised, London-dominated UK.

This trend has intensified in recent decades, with both Westminster and established London-based media outlets constructing a peculiar, fused nation: Anglo-Britain. This is a Britain which is dominated by England, and at the same time its leaders can hardly manage to speak that name. While for many purposes, Westminster only governs England, not the whole of the UK, we’re only too used to hearing references to ‘the country’ or ‘the nation’ when discussing policy that doesn’t apply to Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. Senior politicians frequently make seriously inaccurate statements about the territorial scope of public policies, while similarly sloppy and misleading claims saturate the London media. Inaccuracies of this kind have plagued the government’s public policy communications throughout the pandemic, with repeated failures to recognise or acknowledge Wales prompting many to reconsider their view of the country’s position in the UK.

On the flip side, the pandemic has also provided the Welsh government with important opportunities. Although all of Britain was hit hard by the pandemic, given that health and social care regimes have shared origins and operate within a common basic framework, the policies pursued by the UK and devolved governments were different in a number of respects. For Mark Drakeford, highlighting these differences was a priority. In his Covid communications, he sought to balance co-operation with the UK authorities with robust defence of distinct Welsh Covid policies. Crucially, while explaining Welsh policy, he repeatedly rejected the idea that England provided the norm against which Wales should be judged.

These communications transformed Drakeford’s profile and popularity. Historically, devolved politicians in Wales haven’t enjoyed widespread public recognition, and much more than in Scotland or Northern Ireland, the Welsh public consume London-based media. But during the pandemic, the first minister was broadcast into Welsh homes on a massive scale through televised daily media briefings – and most people in Wales liked what they heard. Hardly known for his charisma, Drakeford conveyed a sense of effective, considered leadership and of shared responsibility which contrasted with Boris Johnson’s approach and had a wide appeal across Wales. Importantly, by standing up for Wales, he enhanced his appeal among people with a strong Welsh identity. Consequently, Welsh Labour has developed an effective ‘soft nationalist’ appeal – at least for now. But questions remain as to whether the party can square this appeal with its commitment to the UK over the longer term.

Yes Cymru.

It’s against this backdrop that we’ve seen the emergence and rise of a new independence campaign in Wales. Initially formed in 2014 and launched in Cardiff in February 2016, YesCymru – a non-party, single-issue movement – has revitalised the debate over independence. By 2020, the campaign claimed about 2,500 members. Doubling in a couple of months in spring 2020, its membership has since then kept on growing, rising to nearly 19,000 by May 2021 to become one of the largest political membership organisations in Wales. Rapid growth undoubtedly placed the organisation under strain, however, and in August 2021 its central organising committee resigned en masse amidst complaints of harassment.

The pandemic is no doubt one part of the reason for Yes Cymru’s growth. Another is that the movement added something distinctive to Welsh politics. Yes Cymru’s young membership has brought a fun, playful energy to Welsh politics, with social media and meme culture helping to draw new supporters. The movement also has a strong image, with branded merchandise – from stickers and coasters to the beanie hats and sweaters – regularly worn by pro-indy activists on Instagram and TikTok.

@basicallycatxAnnibyniaeth !! ##annibyniaeth ##fyp ##foryoupage ##foryou ##xyzbca ##cymru ##cymraeg ##wales ##welsh ##welshindependence ##uk♬ my entire personality – june

The campaign has also drawn celebrity support from the arts, sport and the media – the likes of Charlotte Church, Michael Sheen, Eddie Butler and Neville Southall – rather than conventional politicians, with Church welcoming in 2021 with a song proclaiming that “independence is normal”. What’s more, the campaign’s energy has echoes of the culture around the original ‘red wall’: fans of the Welsh national football team. In fact, there appears to be considerable overlap between the two groups: in 2019, pro-independence football fans marched through Cardiff to a game against Slovakia.

The 2021 Senedd election.

As the May 2021 Senedd election approached, Welsh politics seemed to be pulling in two directions. On the one hand, interest in independence was, it seemed, on the up. If Plaid Cymru had placed a surprisingly weak emphasis on independence in previous campaigns, that changed in 2021 under the party’s new leader Adam Price. And a considerable section of Labour voters could be counted as supporters of independence too – as were three of its parliamentary candidates. On the other hand, on Drakeford’s other flank, the Welsh Conservatives had made gains from Labour among pro-Brexit voters in the 2019 UK general election. The Conservatives were aiming to consolidate and extend their position in Wales, looking to win over more ex-Labour voters who had defected to the Brexit party in 2019. Would 2021 see Welsh Labour be squeezed from both sides – losing indy-enthusiasts to Plaid while the Conservatives consolidated the pro-Brexit vote?

The answer was an emphatic ‘no’. Welsh Labour equalled 50% of Senedd seats, its largest ever share, winning over 40% of independence-supporting voters – not far below the proportion who voted Plaid. How?

The Labour party has been dominant in Wales for nearly a century, longer than all equivalent parties anywhere else in the world, in part due to the party’s long cultivation of a distinctly Welsh identity. In 2021, Drakeford’s newly achieved profile following standing up for Wales during the pandemic won him support from many people who have a strongly Welsh identity, helping Labour sustain this dominance. But crucially, while Plaid voters were heavily concentrated among Welsh-only identifiers, and the Tories struggled to break out beyond the British-identity group, Labour both did well amongst those with strong Welsh identities and garnered significant support right across this identity-spectrum. In 2021, Welsh Labour had what political scientists call a ‘catch-all’ appeal.

There weren’t huge losses to the party’s right over Brexit either. 2019 may turn out to have been Welsh Labour’s low-point among its historic supporters who had voted leave in 2016, with a bigger chunk of ex-Labour leavers who voted Tory in 2019 returning to the party in 2021 than staying with Conservatives. The return of Brexit party voters to Labour was even more striking: critically, voting for the Brexit party in 2019 did not turn out to be a gateway to Conservatism in 2021 – the proportion of voters who made that switch this year was tiny.

A radical federalist future?

But what does this mean for the prospect of independence? The fact is that Welsh Labour remains committed to staying in the UK – though not without some changes. The party is searching for a middle way between the status quo and independence, putting forward ambitious proposals for UK-wide constitutional reform. Ideas around radical federalism and a vision of the UK as a voluntary union of nations are circulating within the party, and together with proposals to use existing devolved powers in more radical ways – including a universal basic income trial – they may gain some traction among ‘progressive nationalists’ in Wales. But all this falls well short of independence, and despite its recent success amongst independence-supporting voters, Welsh Labour’s proposals are unlikely to garner the popular enthusiasm that the Yes Cymru campaign has managed to generate.

The party also faces a fundamental difficulty: reforming the UK as a whole is not in its gift. Scotland or Northern Ireland could choose to break away from the UK altogether. And even while the UK hangs together, the government in London is moving in a different direction. Johnson’s administration seems to be doubling down against devolution – and the superficial celebration of local leadership hardly masks this trajectory. Across England, the UK government is encouraging new, ad hoc and asymmetrical local initiatives. Instead of building strong structures for independent local government, the Conservatives in London are inviting local leaders to compete for Whitehall-controlled money. These processes at once concentrate control at the centre and risk chaotic fragmentation at the level of local governance. What’s more, the UK government is now extending its asymmetric ad hoc approach beyond England, such as the proposed building of a new M4 bypass around Newport despite the Welsh government’s earlier rejection of the project. The UK Internal Market Act, passed in late 2020 despite fundamental objections from the devolved governments, is at the heart of this agenda, authorising London to intervene directly and as it pleases across large swathes of devolved policy. Anglo-Britain is alive and kicking, and if the independence movement continues to grow in Wales, it’ll no doubt face powerful opposition from London.

–

With a growing number of people in Wales embracing a strong Welsh identity, support for Welsh independence in the near future may well rise. But for independence to become a majority position anytime soon, the movement will need to continue to win over those without a strong Welsh identity.

What’s more, with an Anglo-British government in London seemingly set on extending its reach into Wales, the stage is set for a long period of tension between London and Cardiff. Beyond Wales, the prospect of abrasive deadlock also hangs around the UK government’s interactions with Scotland, over Northern Ireland and with the EU. Although it feels like something has to give, Wales, England and the whole of the UK could well be stuck in stalemate for some time yet.

Daniel Wincott is an academic at Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics and directs the Economic and Social Research Council’s ‘Governance After Brexit’ research programme.

Breaking Britain is part of Novara Media’s Decade Project, an inquiry into the defining issues of the 2020s. The Decade Project is generously supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (London Office).