For As Long As the DWP Has Been Killing People, Disabled Activists Have Been Fighting Back

From ‘sectioning’ the DWP to quietly submitting endless FOI requests, disabled people have sustained a decade of resistance.

by China Mills

26 November 2021

Listen to this article as audio:

It was August 2012, with the Paralympics in full swing, when a coffin was delivered to the head office of Atos, the sponsors of the games and the company contracted by the Department for Work Pensions (DWP) to carry out the work capability assessment (WCA), which determines people’s “fitness to work” and eligibility for benefits. The coffin, delivered by activists from Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC), was filled with messages drawing attention to the more than one thousand (at the time) people who had died after being found “fit to work”. A few years later, statistical evidence would link the WCA to 590 suicides in England between 2010 and 2013.

Less well known is that this analysis was the result of disabled activists and their allies contacting leading epidemiologists to research what was then clear to disabled people, but largely ignored by everyone else – that the WCA made people suicidal. Time and again, it has been thanks to disabled people (including, activists, campaigners and journalists) applying sustained pressure, whether through shouting on the streets or more quietly submitting endless freedom of information requests, that welfare reform deaths over the last decade have been made public.

The expertise, knowledge, genius and leadership of disabled people fighting fatal reforms is central to the deaths by welfare project – a database of evidence I am currently co-creating alongside Healing Justice London, journalist John Pring, welfare rights advisor Nick Dilworth, author and DPAC activist Ellen Clifford, artist and activist Dolly Sen and WOW petition co-founder Rick Burgess. Including a timeline from 2010 to the present, the project traces the undeniable connection between welfare reform and people’s deaths.

Yet when asked about deaths, including suicides, the DWP still maintains a stock response: “We take the death of any claimant seriously…but we do not accept the argument of those who seek to politicise people’s deaths by linking them inaccurately to welfare policy.” At most, the DWP concludes that people’s deaths are the result of mistakes in the system rather than a part of the system – the result of systemic injustice and cumulative harm.

Those with the most intimate knowledge of welfare reform, disabled and Deaf people (including those who identify as Mad, psychosocially disabled and neurodivergent), have long contested this – making it known, often prophetically, that welfare reform is fatal. An integral strand running throughout our timeline is the myriad forms of disabled people’s resistance – from 20 wheelchair-users locking themselves to a chain across Regent Street in 2012, to disabled campaigners contacting the United Nations to initiate an investigation into the UK Government’s welfare reform, that would later find “grave and systematic” violations. Disabled and Mad artists have also played a central role in creatively illustrating the devastation of welfare reform over the last decade, while trying to re-envision justice.

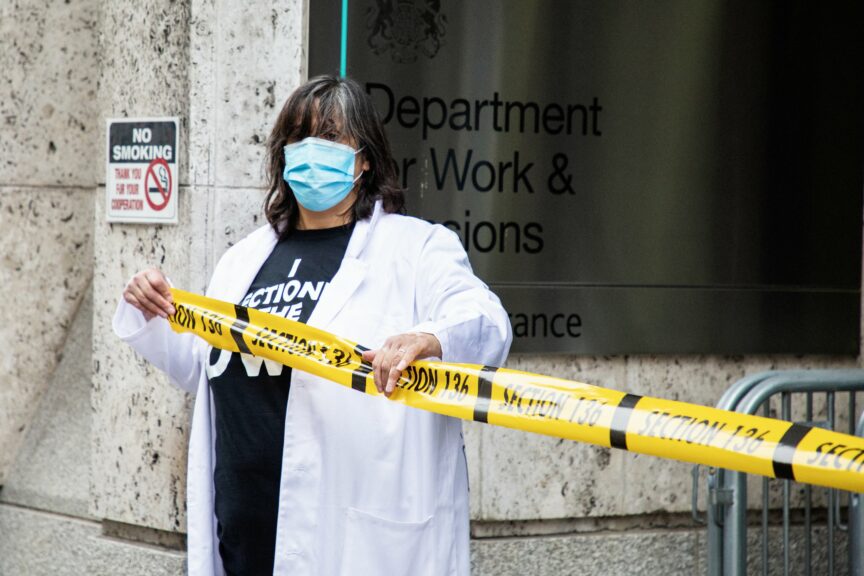

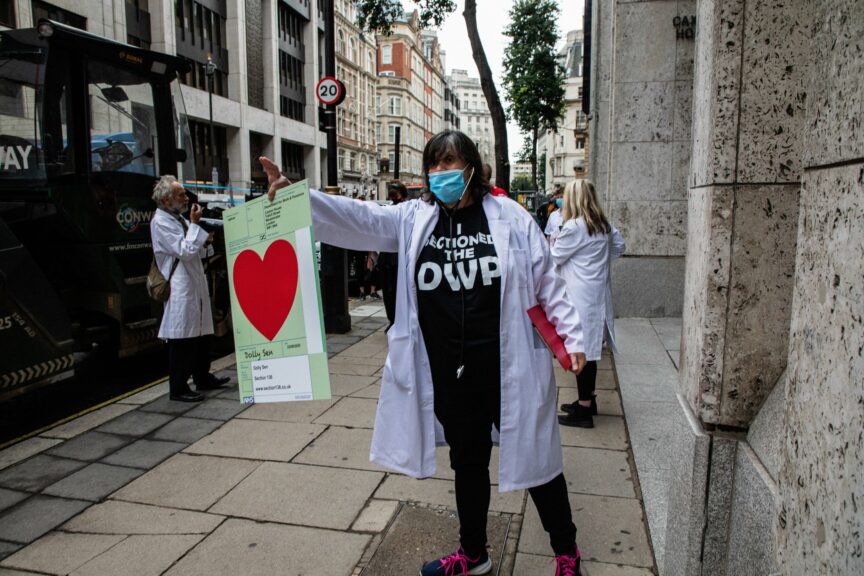

In 2020, Mad artist and activist Dolly Sen “sectioned” the DWP. Dressed in a doctor’s coat, Sen declared the department “a danger to itself and others,” before running hazard tape across the glass facade. The year before, Sen and other activists stood outside the department with large, red broken hearts, each bearing the name of someone who had died due to DWP cuts. One of the people taking part, Joy Dove, has campaigned relentlessly for an independent inquiry into benefit deaths, including the failures that killed her daughter Jodey Whiting in 2017.

Naming those who have died, and recognising how many names we’ll never know, is crucial to disabled people’s fight for justice – whether these names are listed online on Calum’s list or written in paint on the “DWP Deaths Make Me Sick” shrouds that DPAC member Vince Laws created to hit home that “dead people don’t claim”. Jodey’s name appears here too – “Jodey Whiting. Missed a work capability assessment while very ill. Disability benefits stopped. She took her own life.”

Another name at the centre of a cardboard heart held outside the DWP offices was Stephen Carré. Year’s before Jodey’s death, Stephen died by suicide in 2010 after the DWP confirmed its decision that he was ineligible for its then-new out-of-work benefit, employment and support allowance (ESA). For Stephen’s father, Peter, the cause of his son’s death is crystal clear – the “DWP and Atos killed my son”.

Coroner Tom Osborne came to a similar conclusion at Stephen’s inquest, where he found that the rejection of his appeal at being found “fit to work” was a “trigger” in his suicide. Stephen’s death led Osborne to write a report into the prevention of future deaths, which remained unknown until discovered by Disability News Service several years later. Anyone can search the judiciary’s online database of similar reports, all you need to know are some names: Faiza Ahmed, Roy Curtis, Philippa Day, Michael O’Sullivan.

Just over two months after the coroner’s report into Stephen’s death was sent, Paul Reekie’s body was found next to two letters from the DWP, notifying him that his housing benefit and incapacity benefit were being stopped. As a well-known author and poet, Paul’s death was one of the first to spark concerns among disabled activists about the harm being caused by the shift to ESA and the rollout of the WCA.

2010 was the year of “benefits Britain”, in which the government demonised disabled benefits claimants as “scroungers” in an attempt to make largescale punitive welfare reform, such as cuts to disability living allowance, seem like commonsense. No wonder then that 2010 also saw disabled people coming together in rage, fear and solidarity (building on decades of collective action) to form some of the activist and campaigning groups that would come to play such pivotal roles in the years to come. That government cuts and people’s deaths birthed resistance is part of the origin stories of both the Black Triangle Campaign and DPAC, a non-violent direct action group, born from a march against cuts at the Conservative party conference in Birmingham.

While much resistance to welfare reform has taken place on the streets, chronic pain, exhaustion, anxiety, police brutality, lack of accessible transport, incarceration and more mean that not everybody can make it out with a banner. Resistance takes quieter forms too. Resistance is the long battle fought through FOIs submitted by Disability News Service and others over the internal investigations that the DWP carries out when it is considered that its activities may have contributed to the harm or death of a ‘customer’. Resistance is DPAC co-founders petitioning the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) to investigate UK welfare reform. Resistance is internalised, embodied and invisible – an act of survival in a reality that is unbearable – the forms of bearing witness and theory-making that disabled writer and artist Johanna Hedva reminds us are done from bed. Resistance is the life support systems of solidarity and mutual aid for those the government calls a ‘burden’, such as benefits defence workshops, upskilling disabled people to defend themselves against the DWP.

Disabled people’s role in showing the protracted body count of welfare reform provides both cross-movement solidarity and sites of creative tension. Many are fighting for an independent inquiry into the DWP, and a cumulative impact assessment of welfare reforms. Others envision justice beyond the state. Some fight to see the key architects of welfare reform criminalised for “wilful neglect”. Others bring an intersectional analysis, aware of how the criminal justice system criminalises many disabled and Mad people, especially Black people and people of colour.

Seeing the body count of welfare reform, and knowing most names are missing, is heartbreaking. But part of this story of relentless pervasive cumulative devastation is also a story of unrelenting resistance – tacit, written in bed, and screamed out on the streets. What started for me as an investigation into deaths, revealed rich histories alive with resistance. This is a story of disabled people joining forces with bereaved families, bearing witness to welfare reform’s deadly impact, pushing at the boundaries of what we think resistance looks like, and collectively envisioning justice.

China Mills leads Healing Justice London’s Deaths by Welfare project, which investigates the links between people’s deaths and welfare reform.