The Police Are the Domestic Abusers of the Nation

John Apter has had a busy year. In May, the national chair of the Police Federation gave evidence in support of the police, crime, sentencing and courts (PCSC) bill. The bill simultaneously seeks to protect police from scrutiny and accountability while giving them more powers to target marginalised communities. While officers will be protected if they kill someone driving dangerously, Black boys and men will endure suspicion-less stop and searches through new serious violence reduction orders. By October, Apter was allegedly assaulting women at work functions and apparently this wasn’t his first rodeo: he is currently the subject of multiple accusations of sexual violence.

The past 12 months have been a watershed for revelations of the misogynistic rot within British policing, culminating in the recent departure of Met chief Cressida Dick. Of course, this isn’t a new story: police victim-blaming led to serial rapist John Worboys being free to sexually abuse women. The Sapphire Unit – a now-defunct specialist unit designed to support survivors of sexual violence – was caught shelving rape reports, letting perpetrators walk free. But the crescendo, the moment that spoke to the entire nation and cemented a crisis that had been brewing since the Black Lives Matter protests of summer 2020, was the events that unfolded after Sarah Everard was kidnapped, raped and murdered by a serving Metropolitan police officer.

On the day Wayne Couzens was sentenced, Metropolitan Police commissioner Cressida Dick claimed that “his actions were a gross betrayal of everything policing stands for”. This is a curious claim, given what we now know about the events that led to Everard’s death. During Couzens’ trial, it transpired that he had been nicknamed “The Rapist” by his Met colleagues. More to the point, his colleagues did nothing. He brought sex workers to work functions – his colleagues did nothing. He shared sexist messages with colleagues on WhatsApp – they did nothing. And even after the grizzly details of his abuse and manipulation of Everard came out, colleagues went to court to provide him with character references. As Koshka Duff recently wrote of her own experience of sexual assault by the police, the force is quick to close ranks around perpetrators.

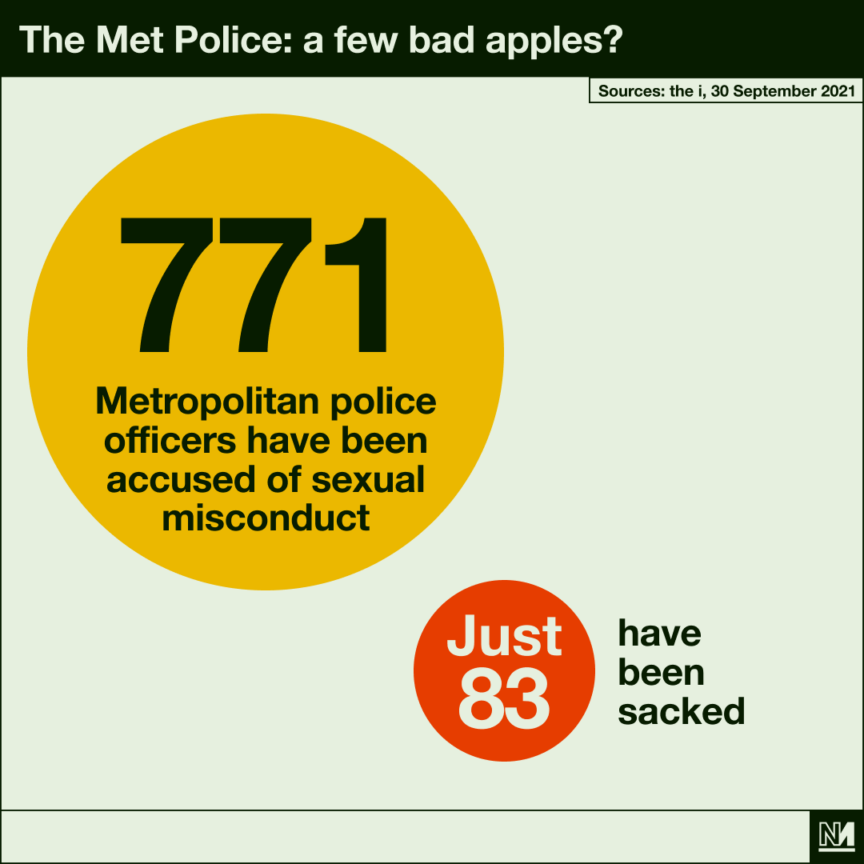

Some say this is a problem with individuals – a few bad apples. Let’s have a look at the whole barrel, then.

750 Metropolitan police officers have been accused of sexual misconduct since 2010 – of these, only 83 were sacked. In the four years leading up to 2020, more than half of officers subject to disciplinaries for sexual misconduct stayed on the job. Channel 4 has revealed that domestic abusers who are also police officers are a third less likely to be convicted than the general public. Even Former Scotland Yard deputy assistant commissioner David Gilbertson has described domestic abuse within the police as “epidemic”. Far from being a “betrayal”, as Dick would like us to believe, Everard’s murderer is the extreme end of a spectrum of sexual and gendered violence in the culture of British policing. But what is it about policing that makes it so attractive to abusers?

Women’s Aid defines coercive control as “an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.” The sexual and domestic violence sectors, off the back of grassroots feminist activism, have done great work to highlight the central role coercive control plays in patterns of abuse. But organisations within these sectors – having had to professionalise, often as charities, to compete for government funding – have largely become depoliticised.

Within these depoliticised spaces, coercive and controlling behaviour simply becomes the means through which individual men exert their power. What is lost is a wider critique of how ordinary social life is saturated in coercion and control and institutions tasked with our protection – principally the police, but increasingly also schools, hospitals and other welfare institutions – are key places where violence, coercion and control are reproduced. The Metropolitan Police Service was founded in 1829 in a volatile climate for the ruling elite, where the organised, industrial working class was on the march and the threat of social revolution was in the air.

The police were created to stamp out this threat: coercion and control are at the very core of their existence.

The police experience what Stuart Hall called a “crisis of hegemonic domination” in black communities. What this means is the black community do not (cannot and will fucking never) *consent* to racist policing. So the police have to police by *force*. A thread. https://t.co/Wog4DsUPe6

— Shanice 😈 (@Shanice_OM) July 29, 2020

The police fundamentally differ from other emergencies services as they are the only ones legally sanctioned to use coercive and controlling behaviour as part of their daily work. Stop and search, arrest, strip search, use of force, detention, mandatory questioning – all could be described as abusive if one civilian did it to another. But this is precisely how police interact with marginalised communities on a daily basis. Let’s look at stop and search. In 2016 government research into the impact of increasing stops across London between 2008 and 2011 found it had “no discernible crime-reducing effects”. The vast majority of stop and searches end in no further action: stop and search isn’t effective at stopping crime. Police know this, but perhaps this isn’t the point.

An inquiry has been launched as a 14-year-old Black boy has accused the Met of stopping him 30 times in two years. He has spoken candidly about how the experience of repeated stops has left him paranoid about leaving the house. And this isn’t an isolated experience. In the first three months of lockdown in 2020, when far fewer people were on the streets, the Met carried out 22,000 searches of young Black boys, a figure equivalent to 25% of all young Black boys in London. This is a pattern of behaviour that targets Black men and boys for intimidation, humiliation, isolation, threats, and violence. It strips Black boys of their personhood by telling them again and again that they are not the person they think they are: they are a criminal. This is the blueprint of coercive control, of abuse and this is the behaviour police are legally empowered to repeat day in, day out.

Policing theorists in the US have a concept of “conditioned response”: repeated exposure to stimuli that elicits a trained response, designed to turn cops into “warriors”. Is it any surprise that violent strip searches against women and pointing guns in Black children’s faces might corrupt someone’s view of other humans? That they might take this dynamic elsewhere? Is it any surprise a man like Everard’s murderer would be attracted to this kind of power? Or that his colleagues, knowing his capacity for abuse, did nothing, for years?

In Apter’s evidence to the PCSC committee, he refers to “[catching] the baddies”; several months later, he was caught himself. Policing exists on a spectrum of coercive and controlling behaviour, and as coercive control is about power, it is unsurprising victims of this behaviour often hold less power in society: women, sex workers, Black folk, the poor. Of course not every officer is a murderer like Couzens, but every officer operates within a murderous system. The idea that we could reform this abuse, tinker around the edges of coercive control, is absurd.

The only solution is abolition.

Shanice McBean is an activist and writer.