To vote or to not vote? In the British Muslim community, this subject always prompts intense, spirited debate. I pose the question to my family group chat, made up of relatives spanning three generations, from my great uncles in their 70s to teenage cousins. “What does everyone think of voting?”, I ask.

I receive an onslaught of revealing replies. “There’s no point in voting”. “It doesn’t do anything”. “The government doesn’t care, why should we?” And then, one of my uncles states: “Voting is haram [religiously impermissible]”.

Growing disengagement.

A 2021 survey by the Labour Muslim Network shows increasing voter apathy among Muslims in Britain. Compared to data from the 2019 general election, 34% of those surveyed said they didn’t vote in the May 2021 local elections, an increase of 7%. The Muslim Census similarly found that if there was an election called tomorrow, 18% of those surveyed wouldn’t vote at all, an increase of 10 percentage points from the 2019 elections. Perhaps the most stark finding from the report concerned young people, a highly politically aware group: one in four 18-24 year-olds surveyed said they wouldn’t vote.

This is an ongoing issue, and voting disengagement is pronounced across ethnic minority groups in general. A 2016 University of Essex study into voting attitudes among British Muslims found higher perceptions of Islamophobia and negative attitudes towards British foreign policy abroad correlated with higher political alienation and, by extension, a lower voter turnout.

In an era of political instability, manufactured culture wars, post-Brexit disillusion and the soaring cost of living crisis, apathy towards the political establishment has reached a tipping point – and Britain’s Muslim community is particularly afflicted. Add the unique political challenges this demographic faces – including structural Islamophobia, state surveillance and the insidious reach of the Prevent policy – and growing political disengagement isn’t just causing further ‘othering’ from mainstream British politics, but also discord within Muslim spaces.

Islamic legalities on voting vary, with different conditions and exceptions specified depending on the particular school of thought and individual interpretation. Scholars from the majority, centrist Sunni school of thought have put out fatwas (Islamic rulings) on when it is permissible to vote and why. These rulings tend to consider the greater good of voting and engaging politically in the country where you live, due to the direct impact of political decisions in your everyday life, centring Islamophobia as an issue to combat by voting for the least worst option.

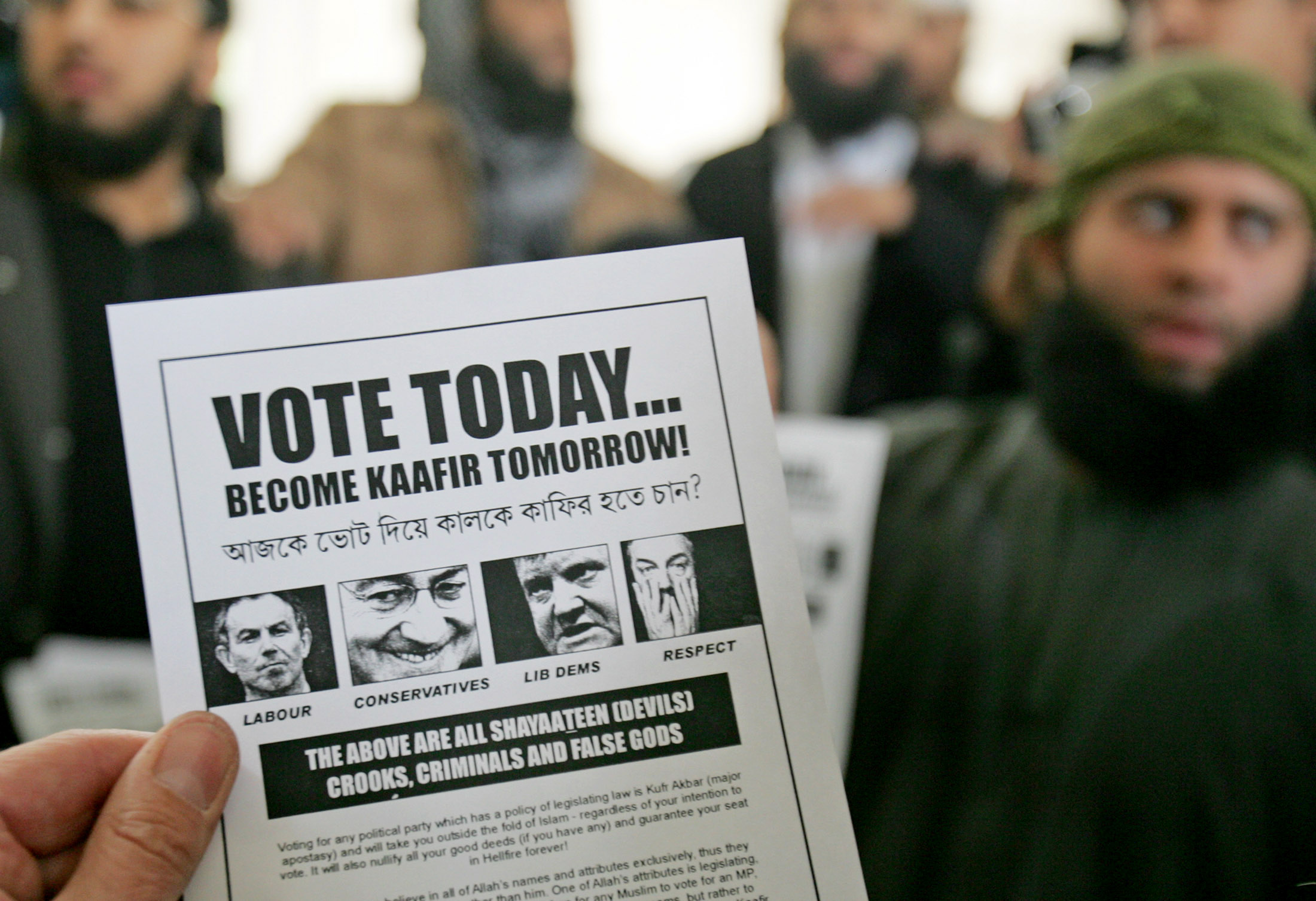

However, there are streams of Islamic thought such as extreme Salafism (a school of ultra-conservative Islamic thought) which prohibit voting, specifically in countries that aren’t governed by Muslims, due to the threat of contributing to a ‘non-Islamic’ system. But elsewhere, many scholars advise Muslims to become politically engaged. One popular Hadith (saying of the Prophet), which states “if people see an oppressor and don’t prevent him, then it is very likely that Allah will include all of them in the punishment”, is cited in particular.

Yet the threat posed by the British parliamentary establishment to Muslims has caused a protective closing of political ranks. Growing up in a predominantly Muslim community in Ilford, east London, I remember those around me being highly politically active and aware; we regularly set up community charity events, clothing collections and distributed food parcels to the neighbourhood. I went to Islamic school as a child and throughout my upbringing, it was reinforced that as a community, we always had each other’s backs. But disenfranchisement created a sense of betrayal when it came to interacting with parliamentary British politics; like I couldn’t be a political actor in all my Muslimness when it came to engaging with Westminster policy.

‘They all lie’.

Ali* is a 23-year-old from Blackburn who has only ever voted once in a council election. He doesn’t believe voting can lead to change. When asked why, he explains he doesn’t vote because “there are plenty of ways to be politically engaged without voting”.

He doesn’t subscribe to the view it’s haram, but does speak of feeling alienated from Westminster politics. Instead, he prefers a form of political participation which involves “individuals and communities banding together to create change”. There’s a sense that large political structures are so foreign and removed from the daily lives of British Muslims that it’s up to the individual to redefine political engagement. However, he does believe Muslim politicians are “incredibly useful in helping Muslim communities in ensuring our faith is accommodated for”.

It’s not just young Muslims detaching from parliamentary politics. Meena*, 55, is a legal assistant. She hasn’t voted in “many years”, she tells me, because she “doesn’t believe anything anyone says”. But Meena is highly active in her community; in her spare time, she manages her local Masjid’s food bank, which is community-funded. This experience “opened her mind up politically as she saw the government had shirked its responsibilities”. Her interpretation of these actions as political broadens what it means to be political and, in her words, demonstrates “taking local politics into our own hands”.

Meena says she’s experienced hostility due to to her refusal to vote. People used to say to me, “you’re wasting a vote’,” she explains. Her reply was always: “What is the point of me putting in a hypocritical, false vote?”

I ask Meena about general attitudes towards voting in the Muslim community. Her response is full of frustration: “Most Muslims I come across have got the Labour hat on – they’ll all do it blindfolded!”

Meena believes there’s a trend within the Muslim community to vote solely to keep the Conservatives out. For Meena, who doesn’t believe in mainstream politics at all, voting or not voting isn’t decisive in creating change for the better.

Hameed Shah Abbasi, 63, makes a point of telling me he has “never voted in this country” because “they all lie!” However, he still engages actively with the politics in his country of origin, Pakistan, watching Pakistani political programs and debating with other family members. Hameed is outspoken and fiercely debates those who defend voting, including other Muslims and members of the South Asian community.

“Once they’ve got the vote, they’re not bothered,” he says. “It’s a big loop of corruption.”

Muslim Engagement & Development (MEND) is a not-for-profit Muslim organisation which seeks to combat low levels of political engagement within the Muslim community through educating British Muslims on the relevance of politics to their everyday lives. Aman Ali, head of community engagement and development, says the government “turns a blind eye to the issues affecting Muslims”. Ali says he has spoken to parliamentary assistants who have said they are barred from talking to key Muslim organisations such as the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) and MEND.

When I ask him about voting patterns within the Muslim community and what he predicts for the next general election, his response is telling of growing apathy: “I wouldn’t be surprised if both the Conservative and Labour parties lose the Muslim vote in the next general election.”

Muslims are constantly on the defensive when it comes to parliamentary politics, says Ali. “If Muslims do vote, it’s a case of the lesser of two evils,” he says. However, he’s noticed an uptick in localised political activity and general political awareness.

The spread of community activism has become an alternative to engaging with elections. Ali notes huge political awareness among younger generations of British Muslims, citing pro-Palestine and anti-Prevent activism in recent years.

For many Muslims like me, our political engagement seems to be a survival mode. I will always remember, as a teenager, a feeling of bitterness watching TV debates questioning whether Islam was peaceful, or seeing Tommy Robinson interviews on social media and practising comebacks in my head. Engaging with a political mainstream that so often seeks to minimise and demonise us can feel like a form of self-harm.

Muslims are becoming more and more alienated, exacerbated only by realities such as the export of extremist Islamophobic Hindutva ideology to the UK (tacitly backed by the Conservative politicians), which erupted recently in clashes across the Midlands, and the government’s muted response. Our political engagement is necessary for our survival but forcing ourselves to engage in the first place can feel impossible.

Khadijah Hasan is a journalist who writes about British and international politics.