It is all too easy not to see class struggle. Our enemies are in power. An ascendant but vapid centre-left is selling out migrants. Oil execs hold the planet to ransom. Bosses gleefully eye AI as the next frontier in labour discipline.

And yet capitalist social relations are first and foremost political social relations. Which means there is always class struggle.

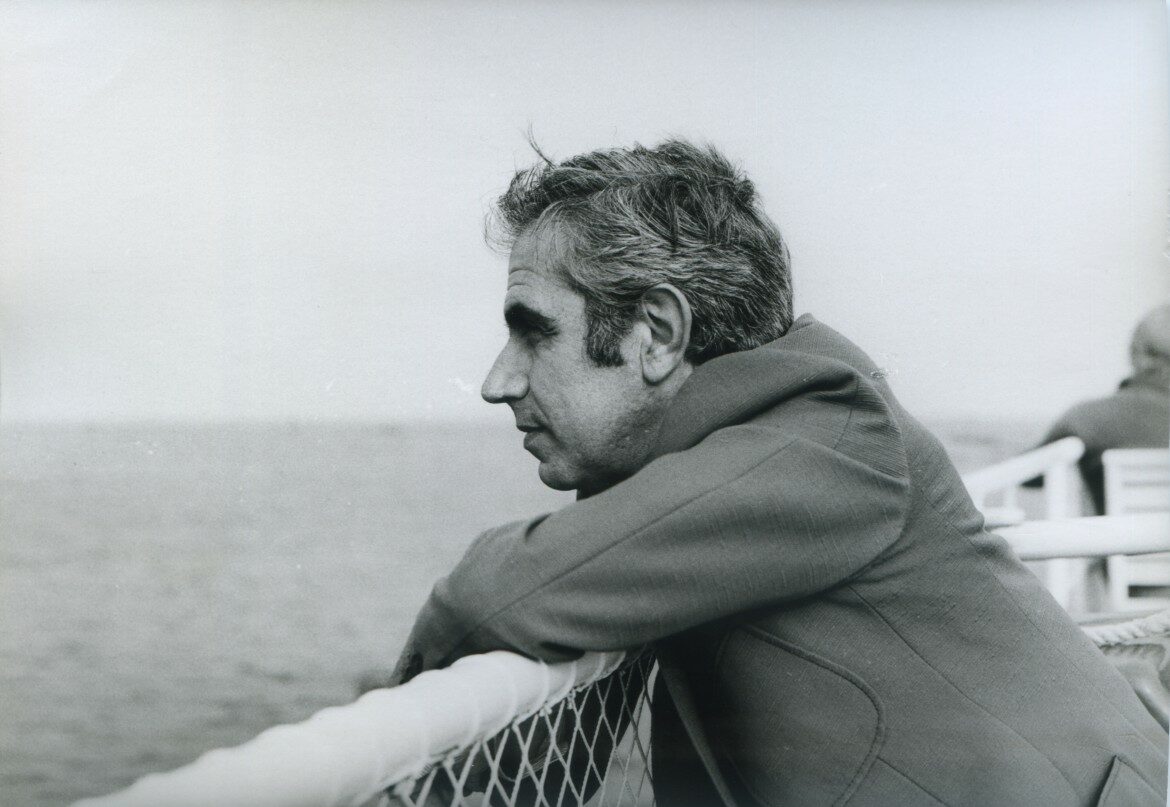

If we had to isolate a core theme within the writing of Mario Tronti, who has died aged 92, it is this. Working-class struggle, Tronti insisted, is not capital’s remainder, but its impetus.

Few people forget the first time they encountered Tronti’s work. His seminal essay, Lenin in England, was for a long time foremost among a small collection of writings translated into English.

“We too have worked with a [conception of capitalist society] that puts capitalist development first, and workers second,” he wrote. “This is a mistake.”

“And now we have to turn the problem on its head, reverse the polarity, and start again from the beginning: and the beginning is the class struggle of the working class.”

Tronti’s insistence on the primacy of working-class struggle within capitalism’s development is invigorating. His writing fizzes with possibility and indignation, arguing for a political conception of capital against an economistic one.

“The concept of exploitation cannot be reduced to the desire of the individual employer to enrich himself by extracting the maximum possible amount of surplus labour from the bodies of his workers,” he wrote in The Strategy of Refusal. “As always, the economistic explanation has no other weapon against capitalism than moral condemnation of the system.”

For Tronti, to understand capitalism in terms of oppressors versus the oppressed was reductive at best. Worse yet, it was actively disempowering to the working class, because it misunderstood the profound meaning of its insubordination.

My first exposure to Tronti’s explosive writing was a one-two punch of Lenin in England and The Strategy of Refusal, both passed to me on rough photocopies made by my comrade, Seth Wheeler, in 2013. Written in 1964 and 1965 respectively, the essays are relics of a creative political and intellectual tendency within Italian communism at the time, operaismo, whose ideas were thrashed out in the pages of the militant journals Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia.

Along with the work of Raniero Panzieri, Sergio Bologna, Romano Alquati, Antonio Negri and others, Tronti’s work was fundamental to the development of what became known as autonomist Marxism – a Marxism that saw the working class as politically autonomous from both capital and the formal institutions of labour.

In his writings, Tronti described the political potential of the working class as being more than its expression in the organised labour movement, or its representation through party political projects. Class organisation is not, he reminded us, reducible to its organisations.

As operaismo followed the working class into Italy’s hot autumn of 1969, and subsequently into the ‘years of lead’ under the banner of autonomia, it would become an inconvenience to later autonomist Marxists that Tronti’s own political trajectory put him at odds with the ideas he had once espoused.

A long-time member of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), in 1992 Tronti was elected to the Senate on the platform of the PCI’s successor, the Democratic Party of the Left (PDS). In 2013 he was elected to the Senate once again, this time as a member of Enrico Letta’s Democratic Party, eventual successor to the PDS, entering a grand coalition of the centre-left and centre-right – an inglorious resting place for a once momentous lineage of Italian communism.

Whilst Tronti himself may have lost faith in the working class to elide its tamest representations, his early theory reminds us that just as the parties and institutions of labour are no substitute for the working class, nor are its intellectuals. Yet even in his early writing, there was always a dual preoccupation with reform and refusal.

“Today the strategic viewpoint of the working class is so clear that we wonder whether it is only now coming to the full richness of its maturity,” he wrote in Lenin in England. “It has discovered (or rediscovered) the true secret, which will be the death sentence on its class enemy: the political ability to force capital into reformism, and then to blatantly make use of that reformism for the working class revolution.”

Such a statement lands differently when, after the failed projects of Corbynism, Syriza and Podemos, it feels as though much of Europe’s pro-revolutionary left has at least dabbled in reform over the last ten years. To borrow a phrase from my colleague Michael Walker, Tronti may have been the original class-struggle social democrat – even if his eventual political destination put him a world away from his original revolutionary motivations.

And yet, even in this moment of searching for the left, Tronti’s words have insight. “The continuity of the struggle is a simple matter: the workers only need themselves, and the bosses facing them. But continuity of organisation is a rare and complex thing: no sooner is organisation institutionalised into a form, than it is immediately used by capitalism (or by the labour movement on behalf of capitalism). This explains the fact that workers will very fast drop forms of organisation that they have only just won,” he wrote.

With Tronti’s passing, we have lost a thinker who wrote eloquently about the tragedy of the way the formal labour movement and the working class can find themselves at odds, who described the way even revolutionaries can find only reformist tactics at their immediate disposal, and who argued energetically for us to develop our own conceptual weapons, rather than inherit the ones handed to us by capital.

These contradictions and their exploration were nothing short of vivifying to those who joined forces in the early years of Novara Media, a project named for Elio Petri’s autonomist classic La Classe Operaia Va In Paradiso, in the early years of austerity, with – again – our enemies in power and a centre-left selling out migrants. I hope they will be again, for us all. Because there is always struggle. E la lotta continua.

Craig Gent is Novara Media’s north of England editor and the author of Cyberboss (2024, Verso Books).