Asylum Seekers in London Are Protesting Poor Living Conditions and Long Wait Times

Some people have been waiting more than two years for a decision from the Home Office.

by Sophie K Rosa

11 August 2023

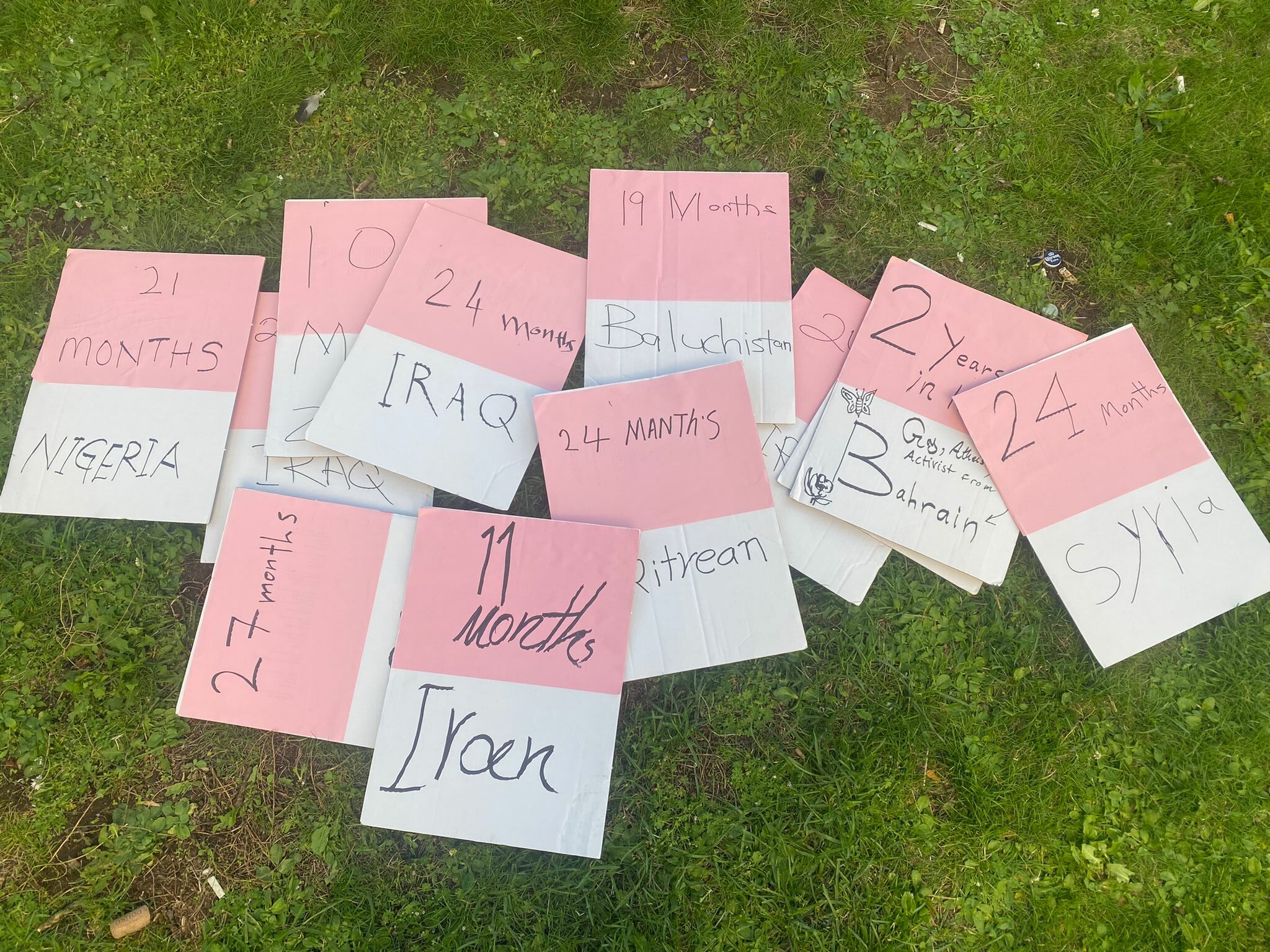

Asylum seekers in a London hotel are protesting against poor living conditions and long wait times this week, after being told they will have to start room-sharing with strangers.

Around 35 asylum seekers were joined by activists outside a hotel in Wembley on Monday, where some residents have been waiting more than two years for a decision on their asylum claims.

Shari, who has been living in the hotel for eighteen months, said the environment makes her “feel like I am in a prison.”

“I feel like my life is stuck in one place,” she told Novara Media. “I’m losing my mental health; I’m losing energy, motivation and inspiration.”

Shari said her physical health has also been impacted by poor-quality food in the hotel; with a government stipend of just eight pounds per week and a ban on working, she can’t afford to purchase her own.

There have been several asylum-seeker-led protests this year, as conditions have deteriorated in the overcrowded, privately-managed hotels many refugees are housed in.

Around 40 asylum seekers were left sleeping in the street in central London in June, after being moved to a hotel that tried to force adult men to sleep four to a room.

Earlier in the year, two groups of asylum seekers in south and east London protested removal out of the city to remote hotels that had been actively targeted by the far right.

The protest in Wembley has also coincided with the removal of 15 asylum seekers from hotels to the Bibby Stockholm “prison barge” in Dorset this week, in a move charities, activists and asylum seekers worry could signify a marked decline in living conditions.

Around 20 asylum seekers who declined to move to the boat face losing government support entirely.

In this climate, organisers decided to broaden the scope of Monday’s protest beyond the room-sharing policy, to focus on the long wait times that strip asylum seekers of their autonomy, leaving them reliant on poor-quality, government-provided accommodation for months or years on end.

Care4Calais organiser Matilda Velevitch said the protest was “very much about being seen rather than being invisible and making the point that they don’t want to be staying in hotels, they want to be contributing to society and rebuilding their lives.”

Residents of the Wembley hotel who spoke to Novara Media were fearful about sharing their rooms. Queer people and political activists feared for their safety, whilst others were afraid of the impact sharing a room with a stranger would have on their health. According to protesters, Home Office letters stated that those with a pre-existing medical condition could request to remain in private rooms, but getting evidence from the GP proved near-impossible.

Monday’s protest was organised by a group of English-language students with the support of teacher-organiser Robin Sivapalan, from English for Action.

After debating the political framing, one asylum seeker wrote a call-out for the protest, which was translated into twelve languages by other hotel residents. “They stuck posters up in the elevators, spoke to people at lunch, shared on social media, scheduled banner-making, painted masks, recommended songs, networked with other groups; two women and a gay man formed a team for an estate basketball tournament which led to us borrowing their sound system,” said Sivapalan.

Conditions in asylum-seeker hotels are often injurious to residents’ health and well-being.

A recent report by the charity Refugee Action revealed that overcrowding and poor hygiene in hotels was causing outbreaks of disease; that hotel food often contributed to hunger and malnutrition; that residents lacked privacy; and that such accommodation contributed to a mental health crisis among residents.

Sivapalan says that in some cases hotels have “entirely microwave food” and that the “institutional set-up” is harmful. “The rules are constantly changing,” he said. For example, he said, “[residents] now have to give their signature to receive a 250ml pot of yoghurt.”

Some women experience “gratuitous harassment,” he said, being “constantly asked about their whereabouts […] [and having] staff knock on their doors in the middle of the night, with male staff entering to inspect if there are men in the room.” One 36-year-old woman had her asylum support cancelled “for months” because she spent one night away from the hotel.

Shari said the room-sharing policy has made an already dire situation worse. “The positive thing I [used to feel] about this country […] was that my room is my own space,” she said. “But now they are snatching this.”

Another resident, Zarith, who has been waiting for his asylum application to be processed for two years and has been living in the Wembley hotel since January, said he had to share a room with a minor in a Cheshire hotel when he first came to the UK. As a gay man, he said, the situation made him fear “allegations of abuse” and for the safeguarding of his roommate, who told him he was 15 or 16 years old. Only after two months of legal support was the minor moved out.

Zarith’s friend in another hotel – a doctor who is working for free in the NHS – had his “room ransacked” by staff in order to make space for another bed, says Zarith. “He’s not the only one.”

M Sonian, another queer asylum seeker, who fled Malaysia due to death threats, fears a mental health crisis if he is forced to share a room, having already faced homophobic abuse in Home Office accommodation. “It is absolutely not safe for me,” he said.

Raed from Syria, who has been waiting for leave to remain for two years, previously resisted an obligation to room-share on medical grounds, because he has epilepsy. However, on the day of the protest he received a letter informing him that he would now once again be faced with room-sharing “because of a big number of refugees in the UK.”

Ali, a refugee activist and journalist from Iran, said the hotel room-sharing policy is simply one “new tactic” among many “to make it harder and harder” for asylum seekers to live with dignity in the UK.

This week, around 15 asylum seekers have been moved on to the Bibby Stockholm barge accommodation in Dorset, which is intended to house 500 men, despite concerns over evacuation routes, fire safety and virus transmission.

The Bibby Stockholm, like the use of hotels, argue protesters, is a tactic intended to rouse hostility among the British public. By housing asylum seekers in costly ways, in certain areas, the government aims to “create backlash” said Sivapalan, and to “gain the support of the bloody-minded and racist [by] visibly demonstrating that asylum seekers get the worst treatment in a period where the settled population face hardship.”

The government claims that Bibby Stockholm is a cost-saving measure – but where hotel accommodation costs £5.6m per day, the barge may only save £10 per person daily. In fact, Sivapalan believes the policy is “symbolic,” intended to “create backlash in a small tourist town […] [and to habituate] the wider population to visible injustice and cruelty”.

Care4Calais’s Velevitch agrees that costly barge accommodation is “a political manoeuvre without a doubt, the living conditions [intended as] a deterrent.”

Protesters told Novara Media that long waiting times are also causing mental illness and poverty, often keeping people from their loved ones for years at a time. “I know that the Home Office has disposed of some people’s applications,” said Velevitch. “They are currently having what they describe as ‘IT issues’, which means I believe that a lot of data has gone missing or cannot be retrieved.”

“I always heard that this country respects human rights,” said Shari. “But when I came here I saw that I am not considered as a human being […] I am not somebody who will stay silent.”

Sophie K Rosa is a freelance journalist and the author of Radical Intimacy.