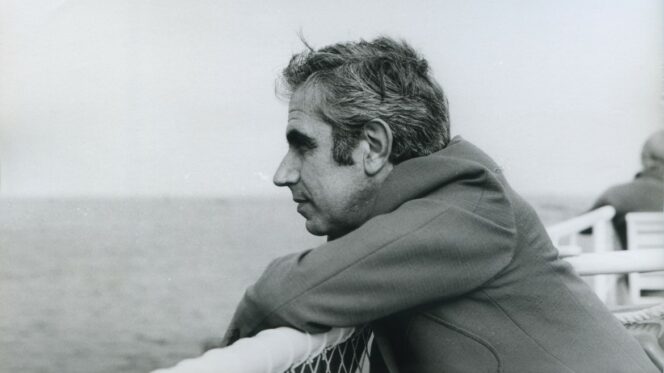

Negri in England: Remembering One of Communism’s Great Optimists

A comrade once said to me: “You know, in Italy, no one understands why Toni Negri is so popular in England.”

I thought of the books on my ‘Italian communism’ shelf and how many of them were authored by the political theorist, and how many of my comrades had similar shelves on their bookcases, but I didn’t have an answer. After all, Negri didn’t speak much English and I can’t speak Italian. I’ve never even been to Italy.

To this comrade, it made our apparent fascination with the radical Italian Marxism of the 1960s and 1970s all the more incredulous. Now, aged 90, Antonio Negri has died, and the question still stands.

The alter-globalisation movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s had a profound influence on those with whom I’ve organised and developed political ideas. Its blending of street politics, cultural and aesthetic creativity and unapologetic anticapitalism railed against the ‘end of history’ at a time when the neoliberal consensus appeared to have won out across society.

It was in this context that Empire, a hefty book co-authored by Negri and Michael Hardt, was improbably elevated to bestseller status. The book aimed to articulate a global politics outside of the Cold War era dichotomies upheld by more orthodox quarters within the Marxist left, and in doing so spoke to a movement articulating radical politics in the shadow of the ‘long nineties’.

But more than being a zeitgeist text, Empire was for many English-language readers an introduction into the political orientation of Negri’s own involvement in struggle – a point relevant beyond the book’s pages given the author had in fact written it from prison, serving the second part of a sentence for being ‘morally responsible’ for the armed struggle of the 1970s from his time amongst the founder members of Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power) during Italy’s ‘years of lead’.

During those years, as a militant and scholar, Negri began to develop a body of thought that had started with his involvement in operaismo in the 1960s, when he had edited the influential Quaderni Rossi journal alongside Mario Tronti, who died in August, and others.

Expressing frustration that the political insights of operaismo stemmed from individual factories rather than keeping pace with the development of capital as a whole, Negri said that Marxists needed to articulate “the new social subject”. Capitalism, he argued, now involved “the entire sociality of the relations of production and reproduction”, work had become diffused throughout all society, and the historical figure of the ‘mass worker’ had now transitioned into what he called ‘operaio sociale’ – the ‘social’ (or socialised) worker.

For Negri, this new subject had implications for both political theory and practice. “All concepts that define the working class must be framed in terms of this historical transformability of the composition of the class,” he wrote in 1982.

“As we used to put it: ‘from the mass worker to the social worker’. But it would be more correct to say: from the working class, i.e. that working class massified in direct production in the factory, to social labour-power, representing the potentiality of a new working class, now extended throughout the entire span of production and reproduction – a conception more adequate to the wider and more searching dimensions of capitalist control over society and social labour as a whole.”

But the archetype of the ‘social worker’ was also a challenge to political organisation typical of Negri’s approach, in that it posed the question of what class struggle looks like beyond the model of the factory, the figure of the (male) industrial worker, and the hierarchies of both party and trade union alike.

Here, perhaps, is the stem of Negri’s appeal to the English left: ours is a nation notoriously obsessed with class society yet thoroughly resistant to doing anything about it. Even our trade unions have made themselves content in their role as mediators of capital; indeed, they did so long before it became popular anywhere else. Likewise, the promised ‘British road to socialism’ only asphyxiated genuine militancy or political innovation wherever it arose, even before deindustrialisation killed the last vestiges of formal leverage and reorganised the working class beyond recognition.

How do we make communism when our class is in flux and we cannot count on the political vehicles that claim to represent us? These have been enduring concerns for those on the libertarian left at least as far back as the seventies. Indeed, it is no coincidence that Negri’s chief translator into English, Ed Emery, was a member of the libertarian Marxist group Big Flame, founded in 1970, and the Ford Workers’ Group – both being among the first groups to ask these questions on the English left.

Yet it is interesting to note that while political events and developments in capital led Negri from operaismo to theorising the struggle of the global ‘multitude’, those inspired by his work here have gone the other way, with projects like Notes from Below being testament to a ‘return to work’ among autonomists.

This is perhaps ironic given that Negri himself regularly faced criticisms that he had merely ‘retreated into theory’. In 1976, fellow operaista Sergio Bologna argued that Negri had simply abandoned live factory struggles with his ‘social worker’ hypothesis. Meanwhile, the Comitati Autonomi Operai pointed to the methodological weakness of Negri’s conclusions: “Precisely the undeniable political importance of these phenomena demands extreme analytical rigour, great investigative caution, a strongly empirical approach (facts, data, observations and still more observations, data, facts).”

It’s true that Negri seemed intent to imagine a class ever more diffuse, more ‘transversal’, and increasingly mediated by technology, yet imbued with its potential. Negri was typically animated when forecasting an era of digital subversion, in which the working class of the past is able to wield its political autonomy and its capacity for political refusal through a newly networked global society.

If it sounds implausible now, in the initial years post-2008 this perspective still seemed to make a sort of sense, with political actors from UK Uncut to citizen revolutionaries in Tahrir Square deploying digital communication technologies in ways that were widely thought to be innovative. Today, between the prison of social media and the rise of algorithmic management techniques, I’m just one of a number of Marxists both inspired by Negri and forced to reckon with technology’s failure to liberate our ability to organise politically.

But we should remember that Negri was someone who had really seen revolution defeated, who knew what it meant to be exiled, imprisoned and even sneered at by fellow leftists. He was a militant, a thinker and a prolific writer, but above all Negri was and should be remembered as one of communism’s great optimists.

Visiting England in 2017, Negri said: “Today, in the post-industrial era, the body and brain of the worker are no longer docile for dressage and horse-training by the bosses; on the contrary, they are more autonomous in building cooperation and more independent from organisational command.”

Whether or not I can get behind this sentiment depends how heavily I’m being influenced by the interminable push and pull of the cycles of political struggle. Yet Negri’s words attempt to will into existence a kind of struggle I want to be part of, his immortal value neatly summed up by comrade Rodrigo Nunes: Toni Negri was “a model of commitment […] and a voice enjoining us to believe the defeats of the past weren’t definitive and there were plenty of reasons to start anew.”

Craig Gent is Novara Media’s north of England editor and the author of Cyberboss (2024, Verso Books).