Filth: Disease, Drugs or Looting – Brutal Policing is Always Framed As Protecting ‘the Public’ From Infection

by Eleanor Penny

5 June 2020

As Black Lives Matter protests sweep the globe, streets lately emptied of their usual throngs by coronavirus now heave with crowds of thousands demanding justice.

Those cautious of openly condemning Black Lives Matter have another option for indulging their reaction, such is the charm of a deadly pandemic.

“The irony of protesters chanting I can’t breathe as they raise the risk of catching and spreading a respiratory disease blows the mind,” writes Ben Sixsmith for the Spectator, a publication which had days earlier been championing the end of lockdown, which sprung early to the embrace of ‘herd immunity’ strategies and balked at closing the pubs.

The Telegraph reported scientists’ concerns that the riots are a public safety risk. This was echoed in social media grumblings; “Your protests are mass murder via corona transmission” writes one Twitter user. Some are already bracing for blame; Anja Madhvani writes “When the second wave of Covid-19 hits the UK, please be wary of the media. They will show you pictures of black and brown faces protesting. They will not show you white faces at the seaside, nor white faces protesting. Please remember this when the time comes.”

When the second wave of Covid-19 hits the U.K., please be wary of the media. They will show you pictures of black and brown faces protesting. They will not show you white faces at the seaside, nor white faces protesting. Please remember this when the time comes.

— anja madhvani (@anja_madhvani) June 4, 2020

Rightwingers whining about the safety risks of riots have said little about the public safety hazard posed by armies of hired goons clobbering teenagers over the head and enthusiastically gassing crowds of citizens, of penning mass-arrestees into cramped holding cells without distance, without protection, of the paid officers putting out the eyes of people who want them held accountable.

Cops, in some small sense, have always existed. There have always been palace guards, sheriffs, mercenaries, slave patrols. In the more immediate sense, they are an invention of the last few centuries. That peculiar permanent state institution, with extraordinary, expansive powers of invasion, surveillance, detention, arrest, punishment and summary violence, evolved alongside our current economic system, tasked with protecting the new institutions of private property which underpinned it from the double outrages of theft and dissent.

Even the most fossilised historians can’t fail to note that early advances in UK policing were driven by popular resistance; by riots and unrest during the shift into industrialisation, twinned with the rapid militarisation of colonial land grabs to try and quash local rebellion. In the US, a regularised police force emerged out of the slavery-era task forces that hunted down people fleeing captivity, in what Angela Davis charts as an ‘unbroken line of police violence’.

The idea of the police as a neutral, public, protective, unquestionable institution – if liable to occasionally stray from the path of righteousness – had at some point to be imagineered from raw paranoias of white wealth. It must be reinvented for each new epoch, expanded as police powers seep further into the roots of our everyday lives. This base guarantor of racial capitalism had to forge its political legitimacy with appeals to a public interest in which racialised life could by no means be allowed to participate.

Early UK police forces were called on to quell bread riots and strikes described as the inchoate outpourings of a semi-feral underclass, rank with contagions both actual and moral; whilst colonial police incursions on the indian subcontinent were justified as attempts to quell outbreaks of infectious diseases considered rife amongst the local population. The policeman stood on the frontlines between society’s filth and its true citizenry.

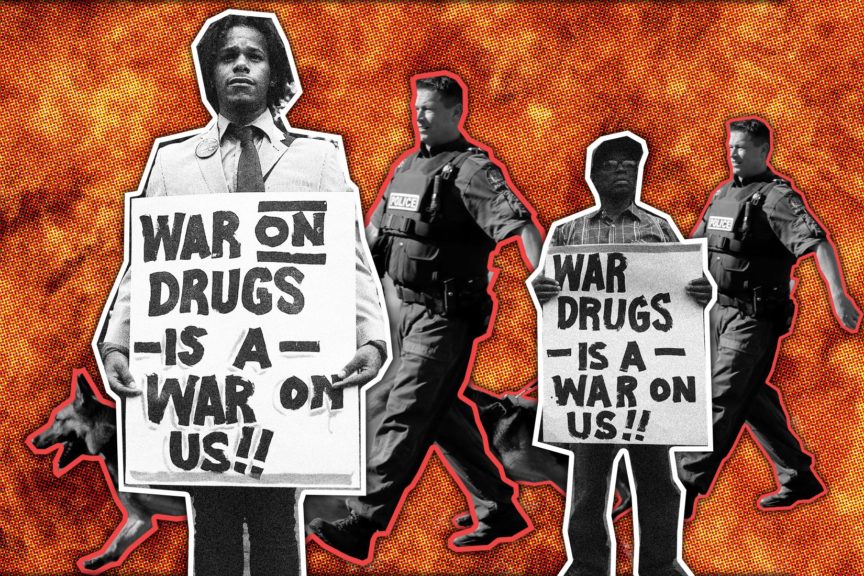

In the 1980s Reagan introduced his militarised redux of the War on Drugs with the solemnity of a surgeon extracting a cancerous mole: “As a parent, I’m especially concerned about what drugs are doing to young mothers and their newborn children,” he announced to the nation, regaling them with tales of babies born motionless and sick. “Help us preserve the health and dignity of all workers”, he pleaded.

The War on Drugs effort ploughed billions more in funding into the police purse, and introduced policies like mandatory minimum sentences and increased police powers used to terrorise black populations. The prison population soared, as did the wealth of the military-industrial complex.

Michelle Alexander notes that the War on Drugs was rolled out long before the US inner cities were suffering through the crack epidemic. In 1998, the CIA admitted to helping drug importers flood cocaine into inner city areas with high BAME populations and few resources to combat the devastation.

Riots too are spoken of as a kind of disease; a grasping social contagion which sweeps easily through an already-stricken body politic. Many clamour to condemn the riots, partially or wholly, as an apolitical upswell of mindless criminality – apolitical, opportunistic, any true political agency corrupted by the actions of thugs. Indeed, the notion of ‘criminality’ itself can claim a dubious medicalised history, rooted in racial science targeted largely at black people, endlessly raked over by ivory tower institutions as both a social contagion and biological weakness. Indeed, the eruption of the London Riots in 2011 were compared to the spread of tuberculosis, with the only option being to ‘stop the infection’.

The contagion model helpfully voids the riot of any political content that we might not want to confront, stripping its participants of political agency. We need never interrogate why the police station and the confederate memorial are burned down, why the mindless looters are setting up food banks on the roadside. It green lights a brutal, rapid escalation of police response. And it helps drive a wedge further between black populations and the ‘public’ whom the police can nominally be said to protect or serve.

Appealing to public health has always been yet more grease for a slippery set of tactics deployed by a government looking to wriggle out of accountability and gloss sustained state violence as benevolent. Those who beat and surveil protestors, those who advocate ‘sending in the troops’ to disperse crowds with bullets and gas do so in the name of health.

Much like concerns of ‘public safety’ and ‘public order’, the task seems universal enough, and its targets vague enough, to brook little disagreement; Who could deny the need to combat a contagion? Who could possibly oppose the sacred duties of public health? But drill down a little and you find a very specific, very cautious act of political retro-engineering of who counts as the public, and who must be counted among its existential threats; who is the carrier of contagion, who is the population that must be protected.

Those gasping through tear gas, those being summarily coshed for their ‘criminality’ must, by definition, have been threats all along. The constant partisans of the minimalist nightwatchman state find themselves signing off on eye-watering police powers, just so long as they happen first and worst to other people.

As the threat of Covid-19 loomed large on the horizons of a US and UK not yet devastated by the virus, governments foot-dragged and quibbled over proactive measures to combat the pandemic with bailouts, employment protections, lockdown support. Both the UK and US have seen a staggeringly high proportion of Covid-19 deaths among BAME people, doubling down on hundreds of years of structural inequality with epidemic indifference to the workers vastly more likely to be on the frontlines of the disease.

Both countries happily rolled out new police powers with the disaster opportunism any two-bit autocrat would dream of. Necessary, it would seem, to protect the public health. Whilst gathering without protection in a workplace is legal, emergency powers in the UK give police the power to disperse public gatherings. Why one should be more threatening than the other is a question of political convenience rather than epidemiology.

Among the people taking to the streets in horror at the daylight murder of another black man – of the daily degradation of black rights across the globe, the racism baked into the fundaments of our economy and bolstered by police violence – few are unaware of the very real risks of spreading coronavirus on demos. Masks and hand sanitisers are being doled out – medical stations set up and torn down by officers of the law. Social networks are awash with a steady flow of flyers and DIY lists of how to minimise the risk of transmission during and after demonstrations. But as Gary Younge painfully lays out, the choices are not between the safety of isolation and the danger of the crowd when racism claims black lives in the pandemic and in the police station alike.

Melz Owusu of BLM UK stated: “I’m worried about my people surviving, whether we die from corona, whether we die from state violence.”

We are seeing the champions of a public health crisis amongst black people suddenly summon up health concerns to justify yet more state brutality. If we are genuinely invested in protecting people – rather than simply point scoring over a police crackdown – we must ask why people are driven to the streets in the middle of a plague because that seems like the best way to protect life. We must ask how racism has mined our political lives so empty of empathy that a carefully applied baton to the skull can be painted as an effort in medical attention. How there is so little to be lost.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the fifth instalment in her series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.

Part one is here: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground

Part two is here: Racist Scaremongering Around Covid-19 Is Nothing New. We Have Always Blamed Racial Others for Disease

Part three is here: Space Junk Is Always Somebody Else’s Problem – But Eventually Someone Is Going to Have to Clean It Up

Part four is here: Coronavirus Has Shown That Cleaners Are Essential, but Labelling Them ‘Low-Skilled’ Legitimises Exploitation